“Walkable Cities.” This little buzzword has been on a lot of people’s tongues lately, hasn’t it? Mine included! The burgeoning young urbanist and pro-housing movement (a.k.a. YIMBY) that’s sweeping America’s cities these days sure does love walkable cities, and I do too. They might also say things like:

“We have to build walkable cities to save the environment!”

“We’re gonna need to start riding bikes and taking transit to fight climate change!”

“Density is necessary to combat inequality!”

“Suburbs are racist!”

“Fuck cars!”

Full disclosure – I think all these statements are, more or less, true. But my friends, you’ve got to stop. Building good cities isn’t a penance we must impose upon ourselves to atone for the sin of being American. Building good cities isn’t a sacrifice, it’s a blessing. People like to live in good cities. They pay thousands of dollars to travel to good cities just to pretend they live there for a few days.

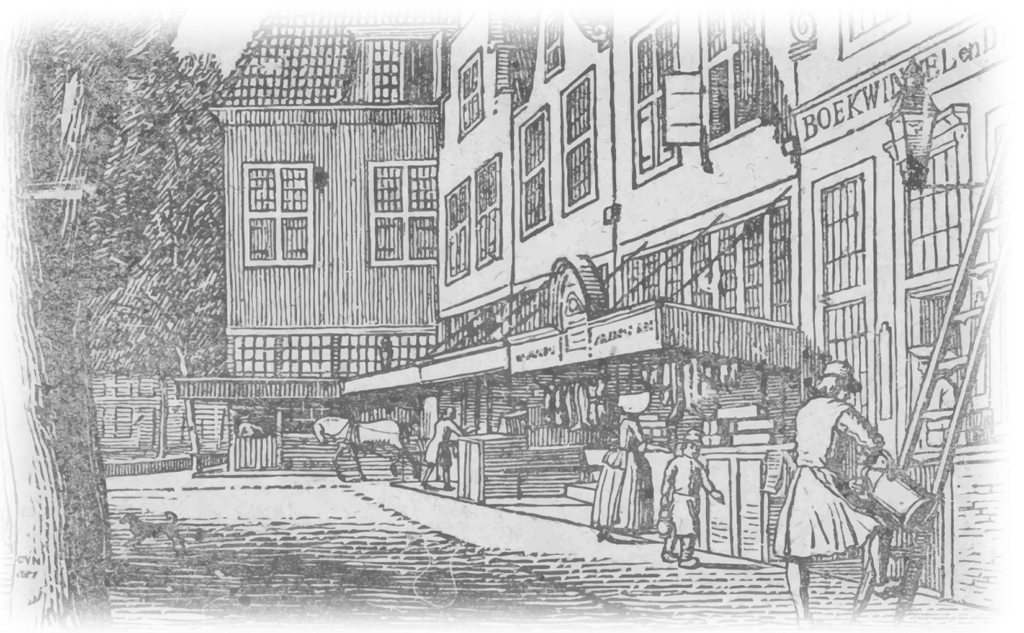

The most beautiful and walkable cities in the world – Siena, Prague, Budapest, Florence, Tokyo, Amsterdam, Quito, Edinburgh, Marrakesh, Riga, Lyon, Boston, Dubrovnik, Venice, Quebec City, Kyoto, Havana, I could go on, but let’s not forget our own Old Port – were not built with grand centralized plans written by governments and their private-sector partners imposing their will on a skeptical populace. They weren’t built by board meetings and approval processes. They weren’t built by moral crusaders or technocratic experts. They were built organically, little by little, by the people who live there. Generations upon generations of urbanites forging and refining their cities in the twin interests of utility and beauty. The innate telos of a city points in this direction.

“Aren’t these just tourist traps? Isn’t this like Disneyland?”

First of all, y’know, people like Disneyland.

The ability to live, work, shop, gather, eat, drink, socialize, learn, worship, relax, and vote all in places within walking distance of one another wasn’t always a privilege for the rich. This was once the common entitlement of all, from the wealthiest districts to even the poorest working-class neighborhoods.

Our cities were stolen from us and sold back to us as luxury.

Good, walkable cities and neighborhoods are expensive today, and this is a revealed preference of the people. People want to go to these places, and to live there, so demand is high, while supply is catastrophically low. But there’s no reason that they have to be filled with luxury apartments and gift shops for tourists. If we could build them freely, they’d naturally be filled with all kinds of housing, and more useful businesses. It is often said, “People don’t want to live in dense cities.” Some people, surely, do not, and for them the countryside is always there. But if that was really true, why do these places attract so much demand?

I’m not speaking hypothetically, I’ve had the lucky opportunity to live and work on the peninsula, and walk about fifteen minutes from my apartment in Parkside to my office in the Old Port. I saved money on car-related expenses, I exercised every day without effort, I could see our beautiful city, I got to see the community bulletin boards every morning on my way in and walk along the Friday Art Walks on my way home. Now that our office has relocated to the suburbs, I spend more on travel, I’m less fit, I see far less beauty, and I’m less in touch with what the city has to offer.

Cities are ancient institutions, the word “civilization” itself is derived from the Latin civitas, “city”, to mean those human societies which build cities. What’s more, they’ve always been hubs for social equality and popular governance, to the chagrin of the landed aristocracy in the countryside. For all work which does not require vast tracts of land, (i.e. agriculture), it makes sense to do it in these bustling communities. From scribes developing written language in the fog of prehistory, to high-tech engineers developing software today, the city is where people, ideas, art, commerce, and cultures interlink and flourish. There is nothing artificial about this process, it’s older than history.

There’s a certain kind of leftish urbanist, however, that doesn’t seem to understand this. They’ve taken up the flag of ‘Walkable Cities’ but are acting with the same condescending, moralistic, exclusionary candor that they’ve so disastrously tainted other good causes with.

Walkable cities aren’t good just because they fight climate change, or because they ameliorate injustice, (though they certainly do both of these things.)

They’re good because they make the people who live in them happy. They’re good because they save the people who live in them money. They’re good because they help the people who live in them to be healthy. They’re good because people want to live in them. Dense cities are a natural development, they have been for millennia.

We don’t have them because they are illegal to build.

If you wanted to build a neighborhood like the Old Port elsewhere in the city, with dense construction, mixed-use buildings, walkable streets, and a natural, garden-like plan, you couldn’t. Not because it’s too expensive, but because these things are made illegal by (among others) the land use code. An arbitrary list of rules dreamed up by the Baby Boomer generation to prevent people from doing what they want with their own land.

Being progressive – moving forward – sometimes means turning around when we realize we’ve made a wrong turn. The way to build good, walkable, dense, beautiful cities is not to have our politicians create rigid blueprints, nor is it to try and apply more and more restrictions on construction. It’s to liberalize the laws which have been placed on our city by decades of anti-city suppression. We have to let communities and individuals build what they want to build, we have to clear out the obstructions that are artificially making our cities worse.

This is a message that we can all get behind. To environmentalists, good cities all but eliminate the need for cars, and so limit the greenhouse gasses produced by them. To progressives, good cities alleviate inequality, providing access and common spaces to everyone, regardless of class. To liberals, good cities have plenty of housing for people to live in, and act as nexuses of democracy and commerce. To free-market libertarians, good cities mean giving people the right to do with their own property what they want to, with only minimal interference from others. And even to conservatives and traditionalists, we’re only asking that we have cities like we’ve had for centuries, as traditional a request as possible.

We should not be advocating for good cities with scolding and guilt, (certainly not with threats.) We shouldn’t say “we are now obligated to build dense cities”, we should be celebrating that we’ll be able to build good cities again. We shouldn’t be shaming people for doing rational things like driving cars to work, it isn’t their fault that zoning laws force housing to be built far away from businesses. We should be showing them how we can build a city where they aren’t forced to drive, saving both money and the planet. We shouldn’t fall into tired old partisan squabbles and shibboleths, we should demonstrate what a universal good building walkable cities is.

I’m a proud Yankee. I love New England for its (slightly stodgy) communitarianism, for how much it values education and knowledge, for its deep-rooted impulse to change the world for the better. But that latter impulse, our restless activism, can sometimes manifest unhelpfully. It might be tenuous to ascribe this tendency to our Puritan forerunners (the most literate society on earth at the time), but the similarities can certainly be drawn. Our quasi-Calvinist assumption is that when we face down a problem, we must act against the innate corruption of man. We must build a mass movement of the morally righteous, we must shame our opponents into realizing the wickedness of their position, we must create and enforce laws to serve the greater good, we must emphasize sacrifice and martyrdom.

New England is, in many ways, America’s conscience. And this is why Yankees are over-represented, to our great pride, in the crusades against slavery, women’s disenfranchisement, unjust war, all kinds of discrimination, and the fossil fuel industry.

But not every issue matches this mold of activism, fit for smashing ancient bigotries. Building good cities doesn’t. Good cities are the natural state of being, it’s suburbia that’s artificial. Once we clear out the legal roadblocks propping up suburbia and suppressing good cities, and once we stop supporting anti-city measures, we’ll be swimming with the tide.

We have to be wild gardeners, not topiarists. Topiarists will plant homogeneous bushes in specific arrangements, and trim them to exacting detail, to create a sparse and artificial landscape. That’s not how good cities are grown. Cities aren’t flat lawns with some unnatural bushes. We should make sure that dangerous weeds are pruned and encourage the most beautiful of flowers to bloom, but, for the most part, the natural and diverse growth of the city should be allowed to run its course. We will be rewarded all the more for it.

Ashley D. Keenan – Ashley is an editor of The Portland Townsman, writer on urbanism, local small business-owner, and Maine native. Her work primarily covers the national housing crisis, building sustainable and livable cities, responsible market economics, and New England culture and history. She lives in Portland with her fiance and can be personally reached at ashley@donnellykeenan.com.

Totally agree! Though, it’s not entirely zoning — some of it is Life Safety and ADA code. I’m not saying the intent is wrong or that I’m an expert in it, but I know from first-hand review of development projects in Portland that there are setbacks, mandated windowless walls, expensive elevators and sprinklers, and other non-negotiable encumbrances that prevent us from building cites like in days of yore. On the other hand, few of us in the modern era experience the horror and terror of whole city blocks burning down. So there’s that. But we couldn’t likely build another Old Port today (organically or technically) partly because of Life Safety and ADA.

Another lost device to building burgeoning livable cities is the front-yard storefront. Old timers from the West End could name dozens of mom-n-pop stores that were built directly on the front of houses. A few of these ghosts still remain around the neighborhood, virtually none of them used for retail anymore. Still more buildings around the neighborhood retain the traces where former storefront additions were removed. Imagine a world where you could start a home business by adding a take-away window to the front of your house. Imagine a world where the Greek yaya down the block sells dinners to go and delicacies out her front window, or the foodie in the ‘hood makes homemade ice-cream in the summers. Let’s allow for accessory retail units everywhere in cities, too!

Very good point regarding the other causes for the changes beyond zoning, we can never go back to the exact environment in which those old neighborhoods were built. But I think we should be able to combine the advances we’ve made in disability accessibility, safety, etc. with an ethos for dense, efficient urban communities. Trying to reach for a synthesis.

And I could not agree more wrt the front-yard storefront, it really encourages a lively neighborhood feeling. In Tokyo, many (I believe a majority?) residential structures are built with the first floor being either a residential unit or a storefront in mind. Completely legal according to municipal laws, and adds so much life to communities. Also really encourages small businesses and entrepreneurs. 100% agree with making all residential areas mixed-use, at least for small businesses.