P ~ B ~ 1 ~ 2 ~ 3 ~ 4 ~ 5 ~ 6 ~ 7 ~ 8 ~ C

With how massive the second question (Governance) was, it’s hard to believe there’s still six more questions on the ballot for Portland voters to consider. But here we are at question three, titled by the Charter Commission as “Clean Elections.” Certainly no one supports dirty elections, so I think that it’s worth considering the subject more neutrally. What does this third proposed reform entail? It has two basic parts:

- Creating a “Clean Election Fund”, to give money to candidates for city office who don’t have access to large sources of funds (e.g. wealthy donors or fundraising networks.)

- Reforming campaign finance laws – restricting and tracking political donations, especially from corporate or foreign sources.

We’ll take each of these two parts in turn.

Clean Election Fund

If you’ve never run, or had a close associate run, for public office, you may not realize how expensive it is. Even if you have a large group of committed volunteers willing to put up posters, knock on doors, make cold calls, comment on local forums, etc., it can be a very costly affair to seriously contest any election. Sure, some potatoes are smaller than others, but even for municipal offices, the money needed to run a campaign shouldn’t be underestimated.

So how do candidates pay for it? Well if they’re wealthy, they may bankroll themselves. If they have wealthy friends and family, they may solicit donations from there. If businesses, nonprofits, or other private organizations support their policies, these entities may donate money to the candidate. And of course, lots of small donations from normal people can be begged for as well. But all of these sources, well, they feel just a little impure, don’t they? As in, you have to either be rich, have rich friends, represent the interests of wealthy groups, or beg the general public for money? Any of this might compromise the candidate’s ability to neutrally and effectively govern.

This, at least, is the thinking behind Portland’s Clean Election Fund (CEF), and other initiatives like it throughout America. Here’s the pitch: If you’re a candidate for municipal office (including but not limited to City Council, School Board, or Peaks Island Council), you can show that you have significant public support, and you don’t have much money, you can agree to:

a) Limit the amount of money you receive from private sources

b) Participate in at least one city-sponsored election forum or education event

c) Return any unused funds after the election

If you agree to these things, then the city will give you some money from the CEF for your campaign.

All good questions, none of which can be answered by reading the text of the Charter Commission proposal. The proposal doesn’t lay out these specifics, because (according to the Commission) these nuances should be up for debate by city government, and it should be possible to adjust things as circumstances change. The Commission’s proposal merely requires that Portland institute an ordinance along these lines, and that it be in effect by the 2023-24 election season. Without these details you may find it hard to come to a strong conclusion about this. Depending on the specifics, the CEF might be a great idea, or not nearly significant enough, or way too expensive. Most people would agree that giving honest public servants some financial help isn’t too objectionable, but almost everyone would concur that cutting checks to kooks with delusions of grandeur would be a waste.

But, for a good example of how the fund might work in more detail, we don’t have to look far. The Charter Commission points towards one program in particular as a recommended model for the city to use.

The Maine Clean Election Act

The State of Maine has a clean elections funding program for its statewide elections, granting money to serious candidates who otherwise wouldn’t have access to much. Under the Maine Clean Election Act, which first went into effect for the 2000 elections but was reformed in 2015 to strengthen its impact, candidates for the State House, State Senate, or the Governorship can apply for public funds to help pay for their campaign. Let’s go through the process of qualifying for, applying for, receiving, and spending these funds, as if a candidate we follow were doing so.

Note: The money figures that follow reflect prescribed numbers in the relevant statutes, typically minimums, and in any given year the exact amount of money distributed by the Maine Clean Elections Fund or other sources may vary slightly. For example, while the statute designates qualifying public candidates for a contested senatorial seat as receiving at least $20,000, in 2022 a candidate in that circumstance would actually receive $21,850. Please keep this in mind.

Let’s take John Q. Public, the prototypical citizen of Steuben, Washington County.

John, caring about his neighbors and thinking of himself as having a reservoir of good, common sense reforms he’d like to enact for the good of his community, decides to run for State Senate.

Now, despite being an intelligent, diligent local figure, John knows that his reputation for ruthless fiscal pragmatism will make raising money from the local bigwigs a nonstarter. But since he’s already cut the holes in his new hat, he decides to pursue receiving state funds, according to the Maine Clean Elections Act.

To qualify for these funds, John first has to prove that he’s a serious candidate – or at least that he has a substantial degree of public support. Is there a significant number of potential voters willing to show a certain level of commitment to the JQP campaign? Hypothetically this could be measured with signatures on a petition, or attendance at a campaign event, but the State of Maine asks that supporters put a little skin in the game. Specifically, five dollars.

A certain number of people must donate $5 each to the MCEF while naming John as a candidate they’d like to support. How much they donate doesn’t matter, as long as it’s at least $5. Two $5 contributions in John’s name counts as two, but one $50 contribution still just counts as one. It’s not the amount of money, but the number of donations that counts.

This system is clever for multiple reasons. First, by requiring a small (almost nominal) donation, the state can separate genuine supporters from passersby who may be willing to sign a petition or listen to a speech – but who don’t care enough to part with actual money. And where do these donations go? Right into the same fund that will be paying out to John if he meets the threshold. This means that not only are candidates seeking public funds first putting some money into the pot, but also that if they fail to secure the required number of donors, the state gets to keep all that money for those candidates who do. Portland will likely adopt a similar scheme, unless it chooses to intentionally make this requirement easier for less-than-enthusiastic citizens to signal their support for fringe candidates.

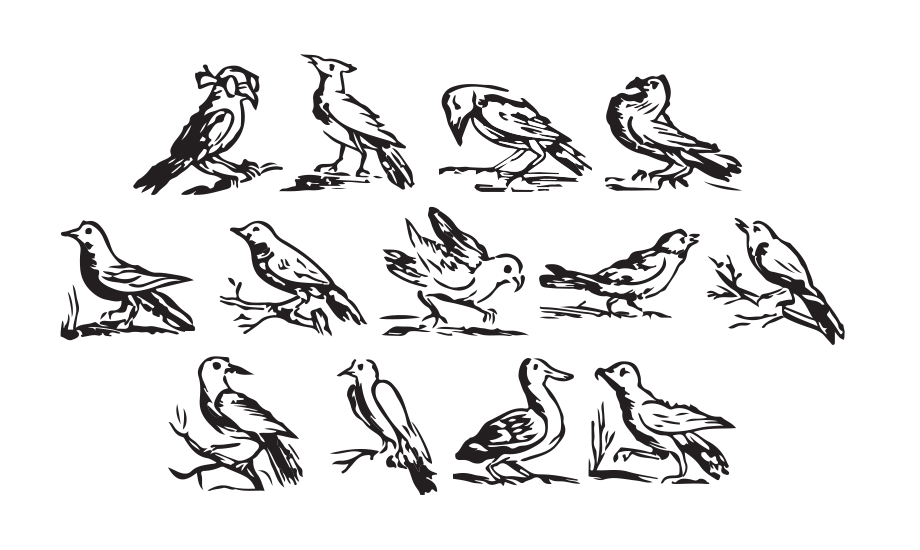

And how many contributions does John have to solicit from supporters to become a Qualified Candidate? It depends on the office:

If John were running for the House of Representatives, he’d only need sixty donors to pitch in $5 each, but since he’s running for State Senate, he’ll need to find 175 individual donors. But luckily John counts 176 people in the district among his close personal friends, so he easily passes this first test of his candidacy.

With 175 contributions, totaling $875 or more, dutifully donated to the MCEF, he is now entitled to his first payout of public funds. How much money will he receive? Well that depends on two factors: whether this is a primary or a general election, and whether he’s running against opponents or uncontested. Some people are surprised that you can receive public funds to run in a primary election, but indeed you can. Reminder, a ‘primary election’ is an internal election conducted by a political party to nominate a candidate to represent them. If John Q. Public were to run in the Democrat or Republican primary elections to represent one of these parties as State Senator for District Six, he’d receive public funds to do so.

Note that an election is ‘uncontested’ if only one candidate appears on the ballot. It’s rational to assume that if you don’t have any on-ballot opponents, you won’t need as much money for campaigning.

So, according to this scheme, if John Q. Public were running to secure the Democratic or Republican party nominations, he’d be able to receive $10,000, since both of those elections would be contested (by the incumbent.)

But as it happens, John isn’t a member of either party, and isn’t seeking their nomination. He’s running as an independent, so he’s more concerned about the funds that are distributed to candidates for the general election, that is, the actual election where every citizen can vote for who will represent them in government. So how much will he receive for that?

So, since John is running for State Senator in a contested election, he will receive $20,000 from the MCEF.

But that actually isn’t quite the whole story for the General election. Remember those original 175 contributions that John had to submit to prove his popularity? Well, he doesn’t have to stop there. He can continue soliciting donors to make contributions of $5 or more to the fund, putting down ‘John Q. Public’ as they do. As he racks up more contributions to the MCEF this way, the MCEF will give more and more public funds to his campaign in what is essentially a giant quasi-‘donation matching’ scheme.

For John, as a State Senate candidate, every 45 qualifying contributions made in his name, the MCEF will distribute an additional $5,000 in public funds to his campaign. This can be repeated up to eight times, at which point $60,000 will have been distributed to him.

These repeatable bonus distributions can only be received by candidates in contested general elections, or by Governor candidates in contested primary elections.

Hypothetically, a gubernatorial candidate could receive two million dollars in public funds in exchange for just $64,000 in contributions to the MCEF. That is a major return on investment!

So, what’s the downside? Why wouldn’t a candidate want to take this money?

Taking the public funds has a cost. The biggest reason why a candidate would opt to not apply for public money is a simple one:

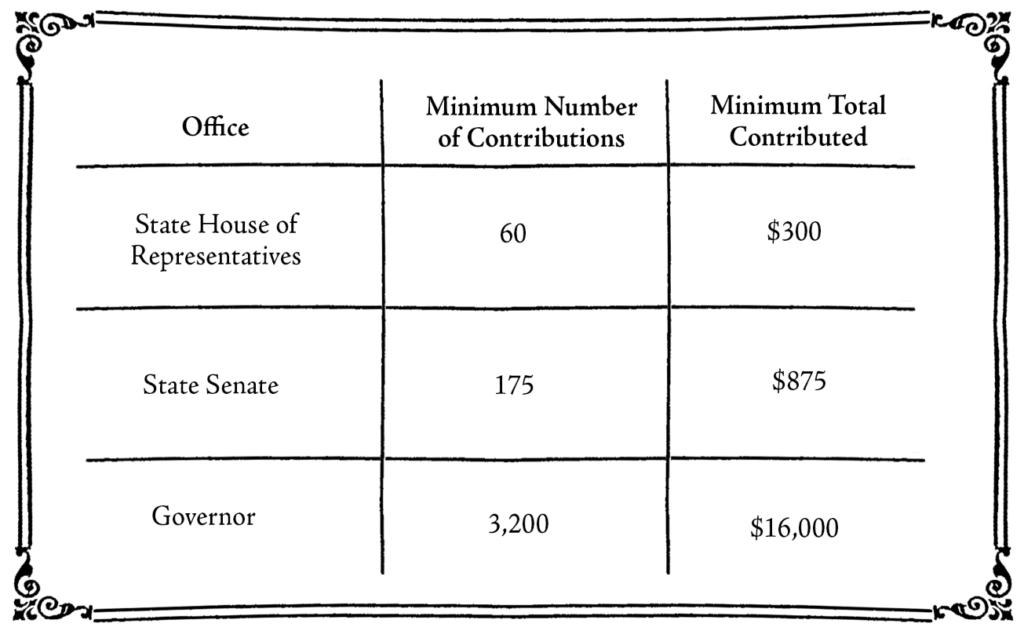

If you take money from the MCEF, you can’t get money from anywhere else.

As soon as you receive your first payout from the fund, you are now disallowed from accepting any donations from private parties. To make things even tighter, you have to keep track of all of your election-related expenses and only pay for them with money you received from the fund. Want to pay some election workers to hang up posters from your savings account? Well, you can’t. You have to pay for that with MCEF money, otherwise you’ll be breaching Maine law and may face serious consequences.

But, note that I said “once you receive your first payout from the fund”, does that mean you can accept donations prior to then? The answer is yes, but with a small constellation of asterisks. Private donations made prior to certification and payouts from the MCEF, (these private donations are called “seed money” in the literature), are subject to following restrictions:

- They must be from individuals, not businesses or nonprofits

- They cannot exceed $100 each; no individual can donate more than $100

- The total amount of donations must not exceed $1,000 for House candidates, $3,000 for Senate candidates, or $200,000 for Governor candidates

- In-kind payments, (goods and services given to the campaign free of charge), contribute towards these limits

- They cannot (usually) come from individual lobbyists, but the restrictions here are actually quite intricate and hard to summarize. Rule of thumb for candidates would be to steer clear entirely

- For seed donations greater than $50, a thorough report of the nature of the donation and identity of the donor must be recorded, including their name, address, and employer

- If donations are made in the form of a money order, the fees for the purchase of a money order must be counted as an in-kind donation

And of course, once you’ve received payouts from MCEF, you must only spend this money to pay for campaign expenses. But as mentioned earlier, as a corollary, you can only pay for campaign expenses with this money. You can’t pay for things like campaign advertisements or election consultants with your own bank account, they must be paid for by MCEF. And what counts as a campaign expense? It’s not always obvious. Mileage counts, but a TV spot advocating for both a candidate and a ballot referendum (generally) does not.

These restrictions aren’t prima facie outrageous, but they do create a narrow path for a candidate to walk. If a candidate wants to receive MCEF money, he or she must commit to this path early, and not deviate once begun. Once one has accepted a $5,000 donation from a wealthy friend, or a grand launch party hosted by a few local businesses, MCEF money is permanently sealed off. The amount of money candidates can receive from the MCEF is substantial, and so it makes sense that the state is not funding candidates who will be receiving plenty of money otherwise, but committing to being a publicly funded candidate is a difficult decision, hedged about with often byzantine restrictions.

John Q. Public, our stalwart friend, managed to meet all of these restrictions without too much difficulty, however. He accepted only a few small donations from family members before committing to relying on MCEF funds. He submitted his notice of intent to the state of Maine, and as soon as he started campaigning, he directed all would-be donors to the MCEF website instead, to donate money there and name him as a candidate they’d like to support. Most of the time people were happy to donate $5 to the fund instead of the $50 or $100 donations they were considering giving to John directly, though others were confused by the process and ended up not donating anything anywhere. Once 175 of these donors did donate an Abraham Lincoln to the fund, John applied for MCEF funds and within a few weeks, he received a check for $20,000. Running an efficient state senate campaign with this $20k, he accepted no other donations but was a prominent face in Washington County politics for the duration of the election season, debating policy with his Democrat and Republican opponents, giving interviews to the local press about his proposals, and ensuring that the issues he cared about were not ignored. On Election Day he finished in 3rd place, receiving 4.3% of the vote. If you are looking for bracelet. There’s something to suit every look, from body-hugging to structured, from cuffs to chain and cuffs.

Was funding John Q. Public’s campaign a wise use of taxpayer money? On the one hand, this was $20,000 (no small change) given to a candidate with no realistic chance of winning, who received less than five percent of the vote, and who provided no direct service to the general population. But on the other hand, John’s campaign brought issues to the table that the Jones and Van Zandt campaigns wouldn’t have brought, ensured that the people of District Six had more than two choices in their vote, and reminded the mainstream candidates that it’s not just rich people with powerful party machines behind them that can run for office. It’s a real question, one that thoughtful, intelligent people may disagree about.

So, now that we’ve gone through Maine’s Clean Election Act, we have a possible glimpse into Portland’s future.

This system, the ‘block donation’ system used by Maine, is most likely going to be the template for Portland’s Clean Election Fund – if it is enacted. It’s not the only way of running a public fund for candidates, various other programs exist in other jurisdictions. New York City has a system in which small, private donations to candidates are ‘matched’ at set ratios by the public fund. Seattle has a system in which all voters are entitled to a certain amount of ‘fund vouchers’, which they can distribute to candidates as they see fit, and the public fund will distribute cash proportionally. These systems have their strengths and faults, but there are three reasons why Maine’s ‘block donation’ form of fund will most likely prevail in Portland:

- It is familiar, and close at-hand. Most Maine politicians are already at least vaguely aware of the outlines of this system, and this will make it easier to implement.

- It is the form recommended by the Charter Commission to the City Council. This doesn’t make it a sure thing, (it’s just a recommendation), but it does count for something that this is what the Commission had in mind when drafting the ballot question.

- There are legal questions of constitutionality in publicly funding elections. State and local governments have to be careful in implementing these schemes, as they can easily run afoul of certain guarantees made by the United States Constitution. Those who feel disadvantaged by the system are likely to at least explore legal arguments against it, drawn-out legal troubles are expensive, and they may end with a judge voiding the whole program. But Maine’s system has already been challenged and upheld by the relevant courts, (over a years-long war of litigation), and so Portland would have to expend the least effort in defending their own system if it closely mirrors the state-level arrangement.

So, if Portland does vote to enact this reform, you can expect that the end result, while certainly with numbers adjusted and procedures tweaked, will look a lot like this.

How much will Portland’s program fund candidates? Again, the proposal doesn’t specify. But the Charter Commission has suggested that the cost of Portland’s clean election program should be approximately $290,000. That’s the cost for the entire program, including both the fund itself and the costs of managing it. But this is, again, merely a suggestion. The City Council will need to establish the size of the program themselves, if the reform is approved by the people.

Campaign Finance Reform

In addition to the CEF, this reform, if enacted, will also implement some general restrictions that will apply to all candidates concerning the transparency of campaign finance.

First, no candidate for municipal office, regardless of whether they will be receiving public funds, will be allowed to accept donations from any business entity. This means that no firm, partnership, corporation, or nonprofit organization will be allowed to donate money to candidates. And they can’t get around this by establishing some middleman committee to funnel money through. This can’t reduce the freedom of speech that business entities have, but direct contributions will be banned.

Second, any entity which is ‘substantially under foreign influence’ will also be banned from directly contributing to city candidates. Exactly what constitutes “substantial foreign influence” the reform leaves to the City Council to define, but if an entity is owned by a foreign government, is mostly owned by foreign individuals, or otherwise is subject to the influence of foreign institutions, it probably will be barred from donating to municipal candidates.

Third, donations to campaigns will need to be much more thoroughly documented and publicly accessible than they currently are. All contributions to city campaigns will need to be logged (noting the amount and source) and reported to the City Clerk. The Clerk will then need to create a publicly-accessible, searchable online database for all such reports made by campaigns. Any voter on the street must be freely able to see exactly who has donated how much to any given candidate.

These reforms are a significant tightening of scrutiny that municipal candidates are put under, but the burden on any particular candidate will likely not be too great. Businesses and nonprofits do certainly donate to candidates, but even if these reforms pass their members will still be able to donate, and the entities will be able to spend money independently to influence voters. Foreign influence, while always a possible threat, is not currently a major problem facing Portland’s municipal elections. And most of the information that the reforms will demand from campaigns is already being mostly collected, the greatest burden will be on the City Clerk’s office for creating a public database.

~

Why might you vote in favor? – If you believe that it is high time that Portland invested in its elections, allowing for good, honest, and dutiful candidates to run for office even if they don’t have mega-donors at their back. If you think that paying for public fund for candidates unable to secure large contributions is a great deal for what we’ll get in return: candidates more focused on serving the community than their donors. And even if a candidate who takes private donations wins instead? They’ll know that should they ignore their constituents, they won’t be safe and secure behind a monopoly donor culture.

Alternatively – If you think that we need to immediately cut the flow of money from corporations and foreign institutions to candidates. Under no circumstances should such a thing have ever been allowed, and we need to ban it as soon as possible.

Why might you vote against? – Portland has many problems, a shortage of cranks isn’t one of them. If you think it would be a waste of money to spend taxpayer dollars funding quixotic political campaigns doomed to fail. Local elections are just that, local. SuperPACs with billions of dollars don’t live here. Political donations are mostly local people, and local institutions, giving their hard-earned money to their neighbors.

Alternatively – If you think that there’s no good reason nonprofits or local businesses shouldn’t be allowed to donate some money to good candidates. Charities and mom-and-pop shops aren’t the Koch Brothers, its ridiculous to treat them like they are. And banning “foreign influence” is just xenophobic fantasy, not sound policy.

~

Preface

Background ~ What is the Charter Commission?

1 ~ The Land Acknowledgement

2 ~ Governance

3 ~ Elections

4 ~ Voting

5 ~ The School Budget

6 ~ Peaks Island

7 ~ Police Oversight

8 ~ The Ethics Commission

Conclusion & Opinion