P ~ B ~ 1 ~ 2 ~ 3 ~ 4 ~ 5 ~ 6 ~ 7 ~ 8 ~ C

This fifth question has gotten very little coverage in local media. This is surprising, as it is possibly the single most radical change in the entire slate of questions. This reform would not only reorganize the structure of city government – it might cleave it into two distinct bodies.

I understand, however, why it has received a lower level of scrutiny than some of the other questions. We think of the Charter, City Council, the Mayor, and the elections process to be things that we all have an interest in, and a hand in. But School Board has always been somewhat off to one side, mostly a body related to a particular clutch of people: parents with children in public schools, and those in the education industry. If you don’t fall into one of those two camps, (I do not), it’s usually thought of as odd to show a great interest in School Board affairs. If a group of childless adults not involved in education show up to a School Board meeting, it’s often a bad sign.

Despite this, the School Board plays a very important part in city government. Not only do our public schools constitute a massive responsibility for our local representatives, but they are also one of the largest parts of the budget. The budget for Portland’s public schools is so substantial, in fact, and so distinct from the rest of the city’s expenditures, that revenue collected (in the form of taxes, fees, etc.) to pay for the school budget is considered separate from the revenue collected to pay for the rest of the city’s budget. School Board members are elected from the general public just like City Councilors or Mayors are, and they wield quite a bit of influence, both over the city’s finance and over its youngest generations.

But this is not a rallying call for childless, non-teacher adults to start getting involved in the School Board’s business. After all, there’s a reason that we don’t have to care. No matter what the School Board decides, all of its final decisions about how much money to collect and spend has to get the City Council’s stamp of approval. If the School Board asks for too much money, resulting in higher taxes for residents, the Council is able to send the budget back to the School Board and demand changes. Usually, the School Board’s requests are reasonable, and the City Council defers to the Board on most areas of discretion.

Even though I, as a childless adult, am not really “tuned in” to the goings-on of the School Board, I can trust my elected representatives on the City Council to act in my best interest. (Hopefully.)

But the change being proposed with Question 5 is monumental – and possibly illegal.

The Path of the School Budget

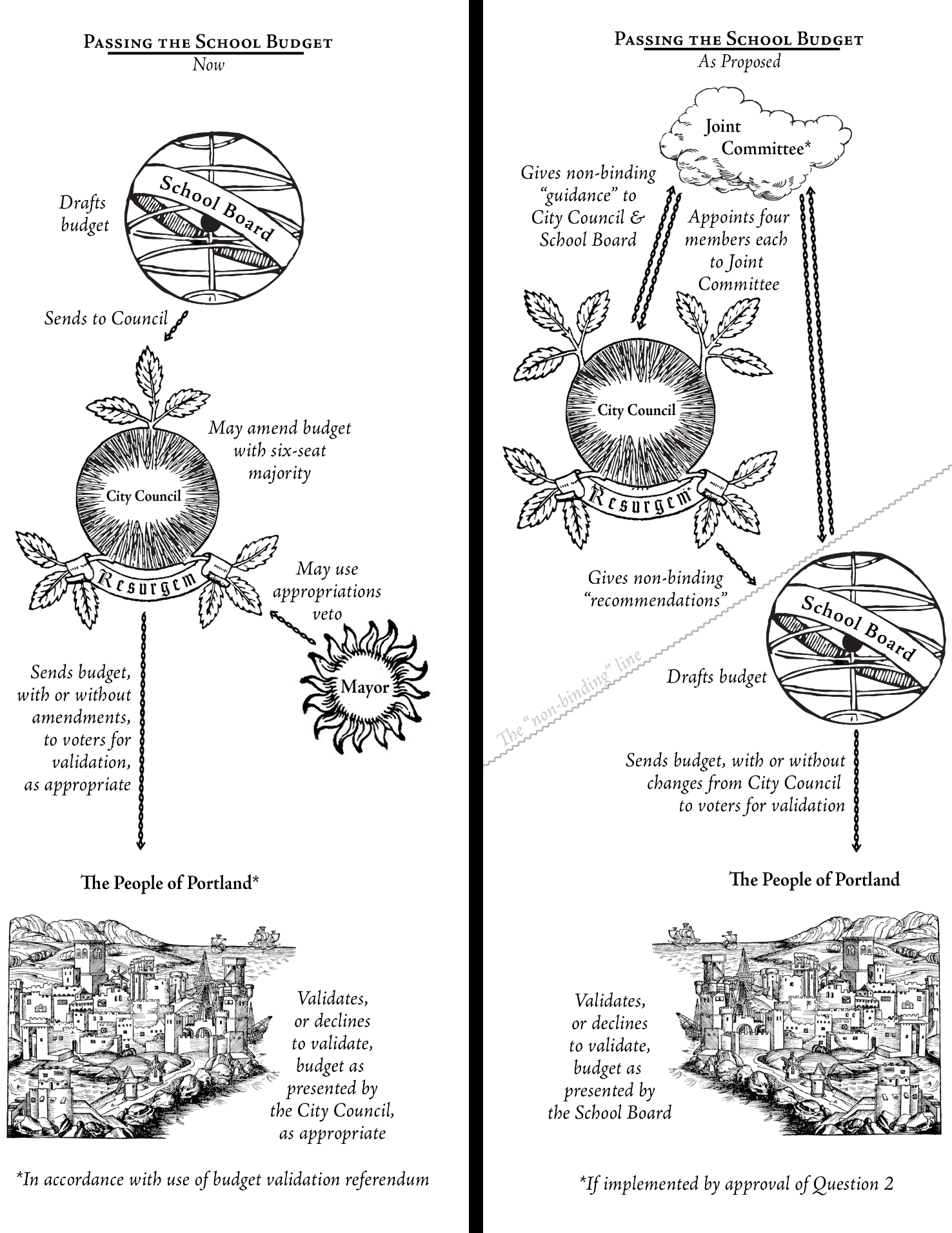

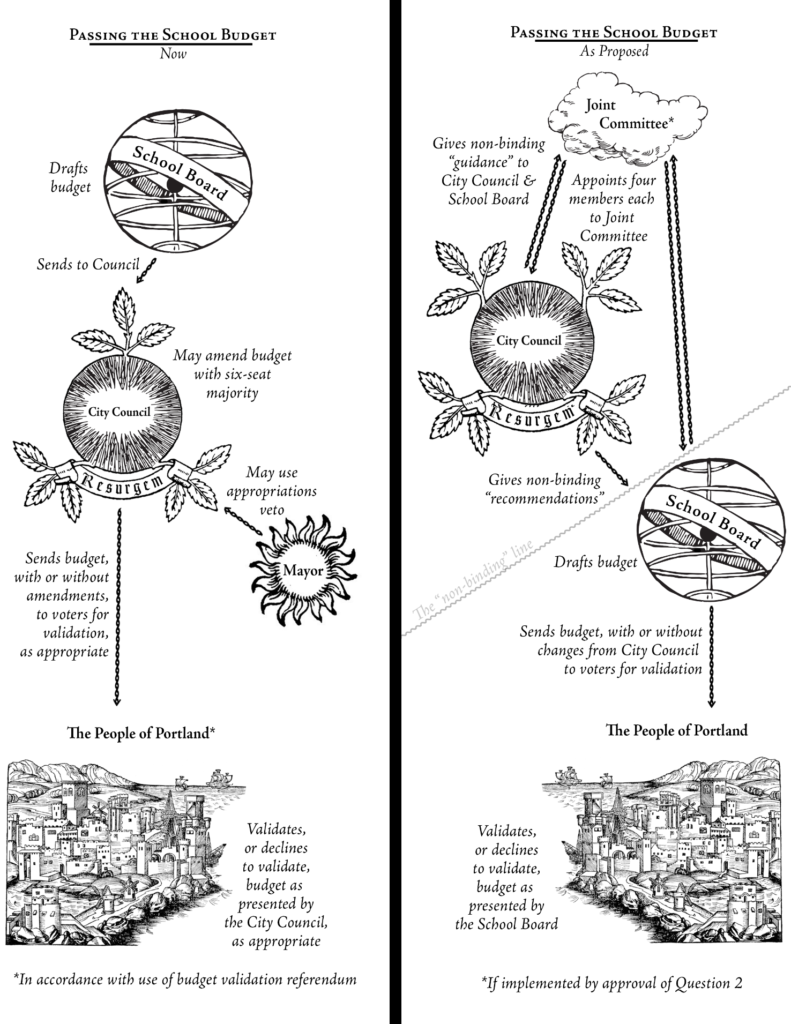

For those of us out of the loop, (including myself until recently), how is the School budget currently created?

According to the City Charter as it stands today, first the superintendent of the school district provides the School Board (formally the “Board of Education”) with information pertinent to drafting a budget, such as the expected costs of the schools’ various expenses, and a basic outline for a suitable budget. After this has been received, the School Board (consulting with members of the City Council) puts together a full, detailed budget, with all expenses accounted for and a total sum to be included in residents’ tax bills.

This budget is then sent to the City Council, who must approve it with a majority of five votes. A majority of five votes can also elect to send more money to the school budget than the School Board requested. However, with a majority of six votes, the Council can slash the total budget to their hearts’ content (within the bounds of state law). The School Board has no power to prevent this.

Once modified and approved by the City Council, the budget is then sent to the general public for final validation. This last step is actually not in the Charter, but rather it’s a provision of state law, specifically Title 20-A §1486. If this Maine law were to cease to be in effect, or if the voters (through a provision therein) choose to forego this referendum, then this last step is not necessary. If the voters send back a ‘no’ vote to the budget, then the School Board and City Council will need to make adjustments and repeat the process. If a true deadlock is reached between the elected representatives and the people, then Maine law has emergency mechanisms that will go into effect, but this is highly uncommon.

Once approved by referendum, the budget is implemented.

Going it alone

Public school budgets are a notorious political football. School board members (often parents or educators) want to provide children with a thorough and well-rounded education, and have fitting compensation for faculty, earning the loyalty of good teachers already here while attracting talented new ones. City Councilors, however, often fail to understand the nuances of the budgets presented to them. This breakdown of communication can result in cuts, or demands for cuts, that feel unfair and short-sighted. Worse, these affect the most vulnerable generation of Mainers; the ones who also represent our future.

While the rest of the government is undergoing substantial rejiggering, (apologies for the jargon), the School Board appears to be declaring bureaucratic independence. Or more accurately, having it declared on their behalf. Question 5 proposes a seismic change: that the School Board report to no one. The School Board, which represents the interests of students, parents, and educators, will have full control over the school budget, and be under the oversight of no one.

Instead, the School Board will draft the budget, then send it straight to voters. Once the voters validate it, then we’re all done. Clean, simple, and fully in the hands of those who most cherish good education.

It’s almost hard to grasp what a radical shift this is. Whether it’s for the better or the worse is, as always, left to the reader’s discretion. But what this reform is doing, in effect, is creating an organ of government which has tax-and-spend powers on the level of the City Council itself. By removing itself from the oversight of the Council and Mayor, the School Board becomes almost a law unto itself. The School Board will be able to raise or lower taxes for residents under its own authority.

Well, almost. All of its budgets do still need to be approved by the voters in a public referendum (which it typically is.) And now, the referendum will be codified in the Charter, so even if the state law changes, the referendum in June will continue to happen every year.

But other than this validation ballot, the School Board, which represents the interests of students, parents, and educators, will now find itself on an entirely separate org chart.

It’s not clear how exactly the city’s revenue collection organs will respond to this, but after speaking with persons familiar with the situation, it’s possible that the city may even end up sending out two separate tax bills, one for the schools budget, one for the “everything else” budget. There will be two separate elected bodies in Portland making decisions about how much money to raise and how much to spend, without any binding interaction between them.

But if you want non-binding interaction, then luckily the reform has you covered. First, let’s hop back to Question 2 (Governance) for a moment. On top of everything else that massive question concerned itself with, it also establishes a Joint Committee on Budget Guidance, made up of four City Councilors and four School Board members. This eight-person committee is charged with the duty “to develop guidance for the city and school district on budget priorities and constraints” and for “submitting the guidance as a proposed non-binding joint resolution to the city council and school board.” So, if both Q2 and Q5 pass, this Joint Committee will be a key point of cooperation between the Council and the Board.

Further, after the School Board drafts the budget, it still needs to present it to the City Council, and the Council can then give recommendations for changes to the Board. But these changes too, are non-binding. At the end of the day, if the School Board is intent on sending its budget to the voters without listening to a word the council says to them, it can do so. Considering that voters only oppose school budgets in very unusual circumstances, having the final say on what goes on the ballot will be a very important position to be in. The School Board may find itself having nearly complete autonomy over its own finances.

Is this legal?

This is going to be a slightly dense section, but it’s very important. Lawyers, as you might imagine, have been involved with the process of drafting the Charter Commission reforms from the beginning. Mostly they’re lurking in the background, occasionally being consulted when the Commission has felt like its on unsteady jurisprudential footing. A substantial reason the question “Is this legal?” hasn’t come up so far is that, in general, the license Maine gives to its municipalities to govern themselves is quite broad. The state has long deferred to the towns on the question of whether they’re allowed to do whatever it is someone is complaining about them doing. But even though the territory of municipal autonomy is vast, if you try hard enough, you will eventually find there is a border.

The legal question, simplified, is this: Who is allowed to tax you?

Under Maine law, the school budget, (and the taxes necessary to pay for it), must be finalized at a “a meeting of the municipal council or other legislative body established by the charter with authority to approve the budget.” (Title 20-A § 2307) This is clearly assuming that the City Council will play this role, but it does mention using an alternative venue: an “other legislative body established by the charter[.]”

If the Charter designates the School Board as an organ with the authority to approve the school budget, can the School Board be this “legislative body” and satisfy Maine law?

Two heavy-hitting law firms were brought in, and they disagree. Drummond Woodsum, engaged as legal counsel for the School Board, says “yes.” Specifically, they say that there isn’t any measure in state law, federal law, or the Constitution that would preclude Portland from doing so. Since the powers given to municipalities are broad, and the legal validity of the Charter is presumed, they foresee no strong objection to this. Furthermore, why would the state law even allow for an alternative “legislative body” if the municipality can’t designate one? Clearly Portland would be acting within the drafters’ intents. And besides, even if the School Board’s credibility as an appropriate “legislative body” is less-than-dazzling, all of their budgets will still be approved by a public referendum, undeniably stamping their decisions with popular approval.

Perkins Thompson, the law firm engaged as legal counsel to the Charter Commission, comes down on the other side, that it is very plausibly illegal. The memorandum explicating their conclusions (strangely) has not been included in the Commission’s final report, and in their other concluding memo (which was included) they affirm their conclusion that all the other reforms they examined are legally sound. But conspicuously absent is this one. Drummond Woodsum’s concluding memorandum is, in part, a direct response to it, referencing specific language, so the absence is even more jarring.

This missing memorandum can be found nestled in the meeting files, though it takes a bit of digging to locate. Here is the link, to save you the trouble.

It seems clear to the Perkins Thompson team who have advised the Charter Commission that a School Board, in point of fact, is not a “legislative body” at all. School Boards do not pass laws, (i.e. legislate), rather they are a “governing” body (20-A § 1(28), (29)) charged with managing an arm of municipal government with funds allocated by the legislature. Portland already has a “legislative body”, it’s the City Council. Identifying a subordinate, governing body like a School Board to this role also is most likely not what the drafters of that law had in mind. Can a city have two “legistlative bodies” at once? The memo also notes that there is much state law which protects the division of powers between town councils and school boards, most of it intended to protect the school boards from uncooperative councils. However, it applies just as much in reverse, and necessitates a level of cooperation.The memorandum cites various other bits of Maine statutes and applicable case law to point out other technical points on which the reform could falter.

True, being confirmed by a popular referendum would give the budgets a significant boost to their credibility, but for Perkins Thompson’s attorneys, the better argument of the law is that this reform would be unlawful. They do not give their opinion that the reform is surely prohibited by law, but nor can they state that is it not prohibited.

The terminology employed in the Maine statute, “other legislative body”, is likely meant to be inclusive of the many Maine towns which do not call their municipal legislature a “council”, but use some other structure and title, such as a “board of selectmen.” This is especially common in smaller towns which rely on that classic New England institution, the Town Meeting.

While you may find one of these arguments more convincing than the other, the fact that two of Maine’s largest law firms, (#2 and #10 as of 2021, respectively), give exactly opposite opinions as to the legality of this reform should signify plainly that there will be blood in the courtrooms over this.

What’s the risk?

And I’m only slightly exaggerating. If Portland authorizes an illegitimate body to levy taxes on residents, the potential consequences are severe. The penalties for a municipality illegally collecting taxes from its residents, per Title 36 §504, is not only the repayment of the tax to the residents, but a punitive 25% premium in addition to any legal costs. If a substantial portion of a school budget are clawed back from the city by litigious taxpayers in a class-action suit, plus lawyer fees and a 25% fine, that is a monumental sum of money that Portland will lose. This is a worst-case scenario, but it should not be dismissed, being raised by the Commissioners of the minority report.

Of course, Maine’s second-largest law firm has advised that the reform would be legal. So, a lot of sound and fury, but it’s not unlikely that Portland is found to be guiltless and the School Board’s independence is affirmed by the courts. Of course, this will still likely be an expensive legal battle to fight, and in the interim the city will be on shaky ground.

An Independent School System

To many of those who see on the far side of this legal storm, however, the promised land is too good not to try for. A School Board freely able to establish its own needs, without needing to appeal to an often-unsympathetic City Council, could represent one of the most groundbreaking innovations for students and teachers anywhere in America. City Councilors have a myriad of interests to balance, while a School Board has only one aim – providing the best education possible. By putting School Board members on an equal footing with Councilors, that’s a strong statement that education matters just as much as everything else a city is responsible for.

But critics see in this exact set of facts a less uniformly pleasant future. Without City Council oversight, School Boards will transform from a subdomain of the city government, relevant mostly to parents and educators, to one in which all Portlanders will now have an interest in getting involved with. Unless the School Board rigorously disciplines itself and, without oversight, resists the urge to raise budgets too much, too fast, they could find themselves being inundated, at meetings and in elections, by the exact sort of people you usually don’t want to see at School Board meetings – non-teacher, childless adults. Or perhaps just as destructively, the public may become disillusioned with the School Board and repeatedly vote down budgets at referendum.

This writer is reminded, however vaguely, of East Ramapo, New York. A school district in which the School Board was taken over by an aggrieved minority with no children in public schools. With a high degree of organization, and clean consciences, these citizens with no organic connection to the public school district ripped and shred the district’s budget to the bones. Obviously, Maine is not East Ramapo in any sense, and while I do not think that such an extreme outcome is remotely possible in Maine, the question of ‘what happens when citizens with no reason to care about public schools suddenly have a reason to get involved with the School Board?’ is an important one.

I hear you, “enough with the hysteria.” It’s fully possible that all the benefits are felt while few of the risks manifest, and those doomscryers who predict financial and political ruin will be looked back on as loons. Nevertheless, these are uncharted waters, and it would serve Portland well to cruise carefully. I apologize if I’m repeating myself, but this titanic reform slices the city government into a pair of distinct bergs. Few, if any, municipalities in America have anything like the proposed system.

This is, in the analysis of the Townsman and our friends, simultaneously the most far-reaching reform proposed by the Charter Commission, and simultaneously the one given the least attention relative to its importance.

A Final Note

To be clear, I think that it is fully reasonable for someone to either support or oppose this reform. However inadequately, neutrality in analysis of these reforms remains one of the highest priorities of this report. This said, it would be neglect of my duties to not inform you of the following fact. Three of the Commissioners voted against this proposal right to the very end, and they then filed a minority report against it in the Commission’s final report. These three Commissioners all have served on the School Board. Of the nine Commissioners who voted in favor of this proposal, none have served on it.

~

Why might you vote in favor? – If you believe Portland is on the cusp of enacting one of the most sweeping pro-education reforms in American municipal history. That freeing the School Board from the shackles of a compromised City Council and allowing it to make decisions for the good of students and educators without needing to keep in mind the careers of City Councilors will undoubtedly lead to better, healthier schools for Portland’s students. This is New England, once the most literate society on earth and still a world-class academic powerhouse. We know the value of education, and shortchanging our pupils for the petty politics of the City Council is an unconscionable sacrifice.

Why might you vote against? – If you believe that the risks Portland would face for doing this are insanely imprudent for something that is simply not worth it. This probably breaks Maine law, and if courts come down against this reform, Portland could be on the hook for hundreds of thousands, if not millions of dollars in clawback payments to class-action plaintiffs. Even if Portland wins the legal battle, to do so will be extremely expensive. And for what? The right for the School Board to raise taxes, essentially unilaterally, without any recourse to the city’s elected officials? To disrupt the long-standing social contract between those voters whom the School Board typically involves and those it doesn’t? To no longer deal with politics in the City Council, but instead bring it home to the School Board? This is all downside and no upside.

~

Next Section: 6 ~ Peaks Island

Preface

Background ~ What is the Charter Commission?

1 ~ The Land Acknowledgement

2 ~ Governance

3 ~ Elections

4 ~ Voting

5 ~ The School Budget

6 ~ Peaks Island

7 ~ Police Oversight

8 ~ The Ethics Commission

Conclusion & Opinion