P ~ B ~ 1 ~ 2 ~ 3 ~ 4 ~ 5 ~ 6 ~ 7 ~ 8 ~ C

This reform is perhaps the one that, at first glance, seems to be quite impactful – but, on balance, will probably only rarely meaningfully affect the outcome of city elections. The question asks voters whether it ought to be that:

“For elections conducted by ranked choice voting where more than one person is to be elected to a single office… the winners shall be determined by a proportional method of ranked choice voting.”

We don’t need to get too deep in the weeds for this one, but you still probably want to know exactly what voting for this reform would entail, so, here we go.

As you probably know, Portland was a pioneer in implementing Ranked Choice Voting (RCV), where instead of voting for just a single candidate, we rank any number of candidates according to our preference. Election operators than use this ranking data to tabulate a winner, eliminating candidates who do not receive enough votes and redistributing ‘their’ ballots to those candidates whom the voters ranked after them. In this way, even if a candidate is not the most popular among 1st ranked ballots, they can still win if they have a significant amount of 2nd or 3rd ranked ballots, for example. And as a corollary, even if a candidate has the most 1st ranked votes, if they’re otherwise detested by the majority of voters outside their devoted minority, they will lose.

There are many reasons to support RCV. It helps third-party candidates, whose supporters no longer need to worry about sabotaging their preferred mainstream party by voting for them. It incentivizes candidates to build their broad approval rate, appealing to the whole electorate, rather than fostering a hard core of dedicated supporters and viciously attacking their opponents. It selects candidates that more people are more satisfied with, even if not their first choices.

Minor note: There are many different methods of implementing ballots and calculating victors in an RCV system. In fact, RCV isn’t really a “system” at all, rather a family of voting systems that all share in a common attribute – ranking individual candidates in order from their most to least favored.

So, what’s this question all about then? In short, while simple RCV systems are fine for elections in which there is one winner, (e.g. the Mayor), they start to hit some uncomfortable ambiguities when the election requires multiple winners, (e.g. three at-large City Council seats.) How can you most meaningfully implement a voting system that fairly represents the electorate in these circumstances?

Well, many research groups and political nonprofits consider Proportional Ranked Choice Voting (pRCV) to be the best option for American cities. The Charter Commission broadly agrees, and would like to implement it in Portland – only one problem.

It’s technically illegal.

Okay, maybe we will get into the weeds a little.

Into the Weeds

If you don’t care about the mechanics of voting, skip to the end and see why almost none of what follows actually matters.

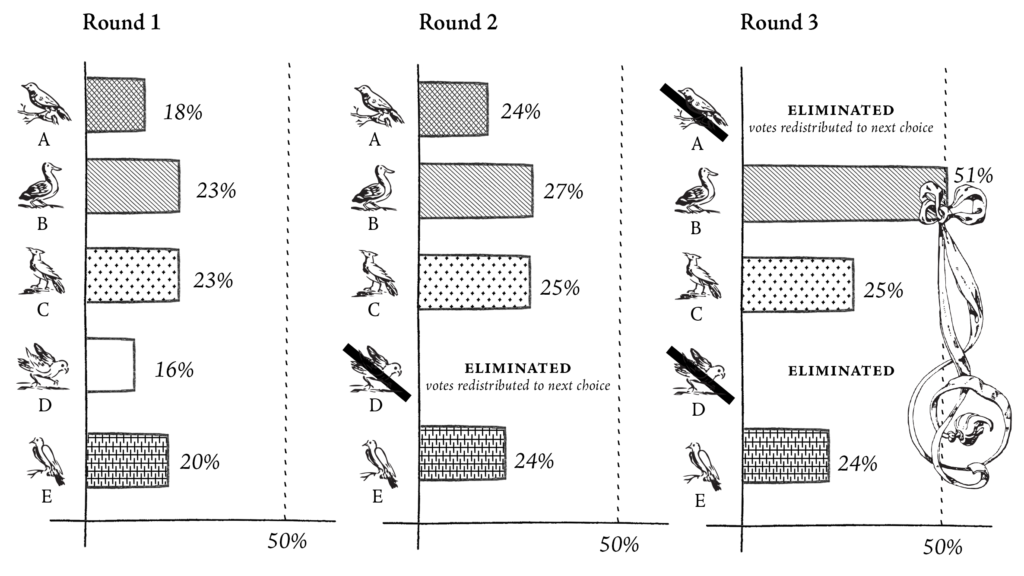

Article II, section 3 of the Charter, revised in 2020 to institute RCV, stipulates that no candidate can be awarded a seat on the City Council or School Board, or be elected Mayor, without receiving 50% of the vote. If no candidate receives 50% of the vote, then the worst-performing candidate is eliminated and his or her votes redistributed to their voters’ 2nd choice. If still no one hits 50%, then the next worst-performing candidate is eliminated and his or her votes redistributed to their voters’ 2nd or 3rd choice, etc., etc. until someone eventually hits 50% of the vote. This is working as intended.

But this precise wording contained an oversight, made accidentally by proponents of the 2020 revisions. When applying this logic to votes with multiple winners, things start to break down. In short, it turns out that people who vote for the same candidate as their 1st choice tend to also have similar 2nd and 3rd choices.

Because the Charter requires candidates for these important offices receive more than 50% of the vote, the only option for the City Clerk in running RCV elections with multiple winners is to use what’s called “multi-pass” RCV, or “sequential” RCV. This is a term that just means after the first winner is calculated using the normal rules, the same ballots are used to calculate a second election, this time acting like the candidate who has already won doesn’t exist. Their votes are redistributed immediately, as if they were eliminated before the election started. The problem with this is that since that candidate’s votes are likely to all go to the same candidates in later rounds, probably candidates who are very ideologically similar to the winner, subsequent winners after the first are more likely to be very similar to the first winner. And this means that slight, organized majorities, and even strategic minorities can dominate these elections. We call this a highly majoritarian formula.

Multi-pass RCV, the system Portland is currently forced to use by the wording of the charter, is warned against by nearly all voting reform groups. So, what do we do?

The solution, somewhat oddly, is to allow winners with less-than-majority votes. The math here gets complex, but in short, votes are calculated with the goal in mind to represent the electorate as proportionally as possible. Since you don’t need a majority to win seats, minorities are likely to win seats proportional to their vote share. To determine the minimum threshold of victory, you have to use some sort of equation like this:

But don’t worry about that for now.

Imagine an electorate where about two thirds are liberal, and one third is conservative. Now let’s say there’s an election to pick three at-large city council seats. Under our current “multi-pass” method, the likely outcome would be three liberals. While under pRCV, the likely outcome would be two liberals and one conservative.

Let’s see how this would potentially play out in both systems by looking at a simplified election where six candidates are running for three open seats as at-large City Councilors. Unlike the previous example, we will now acknowledge that politics matters. We will assume that three of these candidates are affiliated with one party, and three with another party. I have made up the parties, to offer at least a veneer of neutrality, so they’re from the Leaf party and the Castle party.

The Current System: Multi-Pass RCV

First, let’s see what happens under the current system. Remember, three seats are available to win, and candidates need to get 50% of the vote to be elected.

C and X are the most popular candidates, representing moderates in their respective parties. B and Y are more hardline, and A and Z are on the radical wings of their parties. On the first round, no one hits the 50% threshold. Under the current rules, we eliminate the worst-performing candidate.

Z, the radical in the Castle Party, barely got any votes and is eliminated. His voters, predictably, ranked Y as their second choice, since she’s the closest to their policies. But –

Y also did quite poorly. Even with Z’s voters, she topped out at 3%. Y and Z’s voters both ranked X as next, since it would be better for them to have any Castle party member than none at all. So that means –

A, the Leaf radical, is eliminated next. Same as Z, A’s voters prefer the hardline Leaf candidate next, B. But –

B also didn’t receive enough votes. However, once A and B are out, their voters chose C next, the moderate Leaf candidate. She’s now well over the 50% threshold, so she’s the first winner. But we need three winners, remember?

So now we’re going to start again from the beginning. But, we’re going to treat C (who already has a seat) as if she’s been eliminated from the race, and all of her votes are now allocated to their second choices. This is unsurprisingly –

B. Leaf voters, as it turns out, really do not like even moderate Castle policies, and so would rather vote in harder-line members of their own party than moderate members of the other. With both C’s and B’s votes, B is over the 50% threshold and wins the second seat. So now –

We have to do this song and dance one more time. Since C and B are both already in, their votes are immediately re-allocated to their next viable candidate, and that means –

It’s true, A may be on the radical wing of the party, but Leaf voters are loyal, and elect him instead of any Castle candidates. With more than 50% of the vote, A snags the last seat.

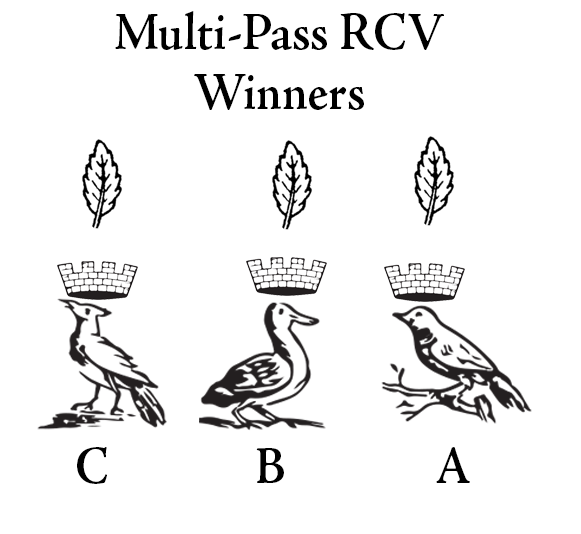

In a stunning victory, Leaf candidates sweep the election. C, B, and A are elected to the Council.

The Proposed System: Proportional RCV

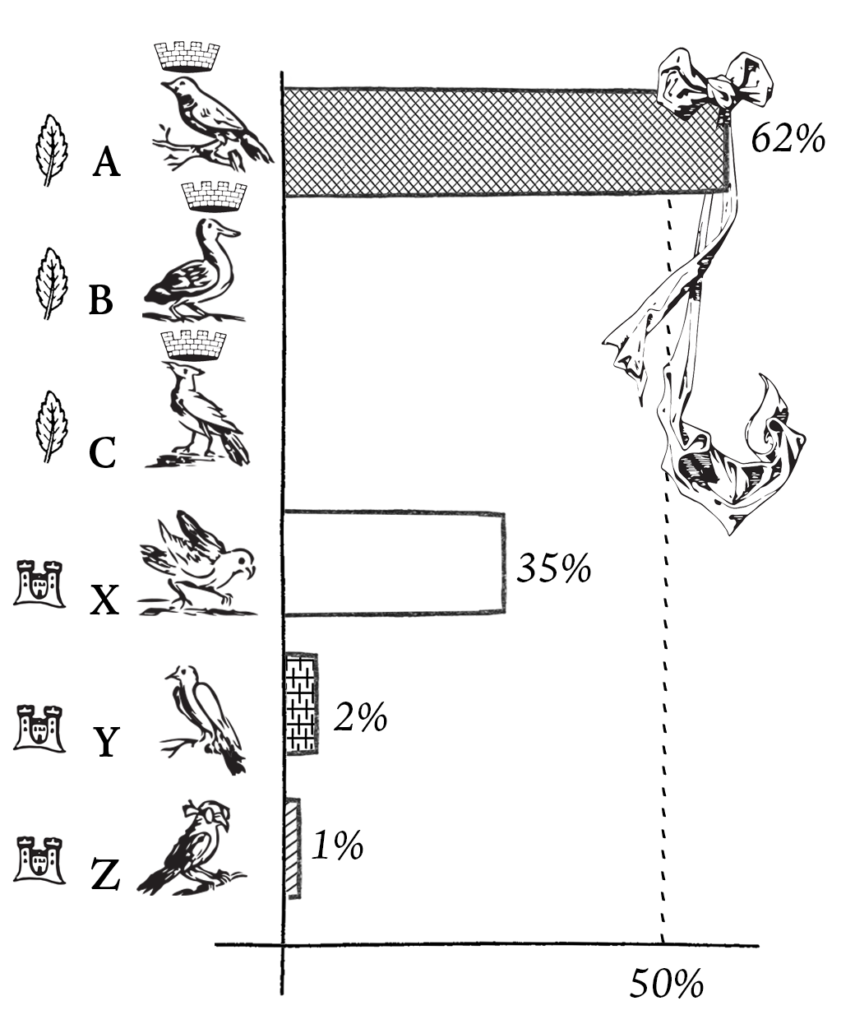

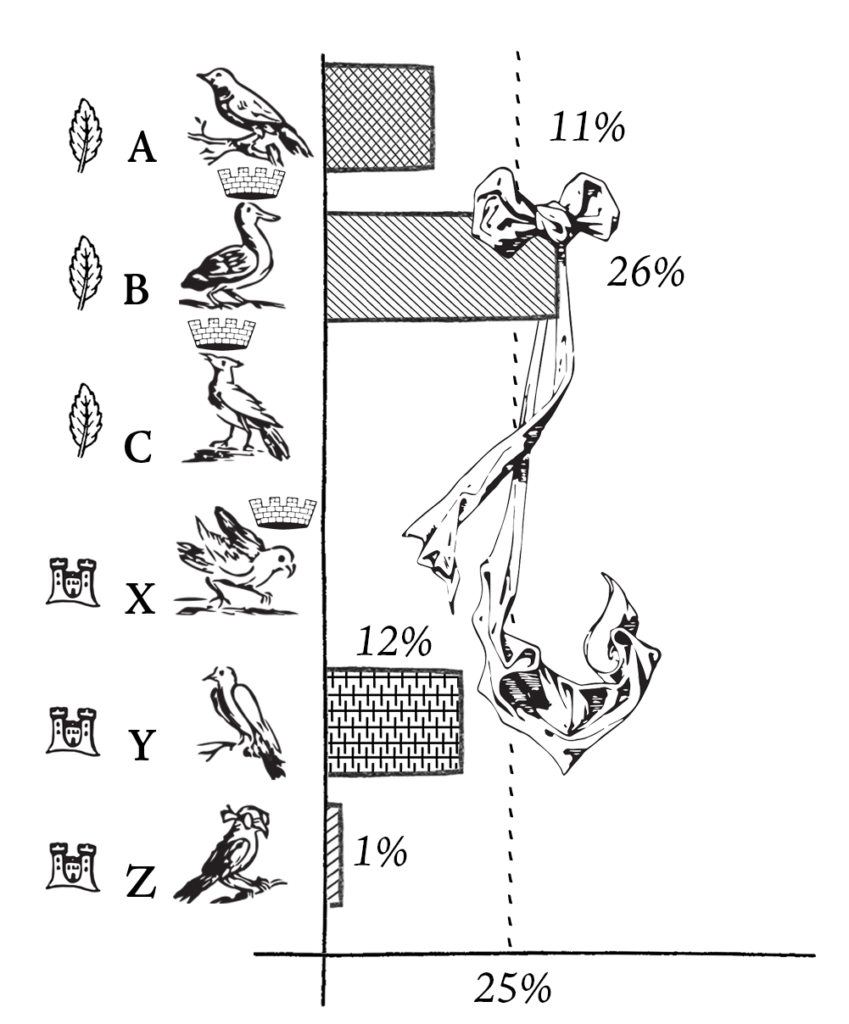

So now let’s look at what would happen if, given the exact same results, with voters behaving the exact same way, the winners were tabulated using the proposed proportional RCV system. Don’t worry too much about the math, but under a sample system, the minimum threshold of victory that candidates have to exceed has been calculated to be one vote over 25%.

Well, straightaway there’s a major difference. C and X both meet this threshold immediately. They are each given one of the three available seats. The Castle party is officially on the board! What happens now? Do we eliminate the lowest-scoring candidate?

Not yet. Before eliminating the worst-performing candidate, the excess votes of the winners are redistributed. This process is the most mathematically complicated part of the process, since the ballots which choose C and X as their first choices now have to be fractionalized proportional to the surplus of votes earned by each. This means if you voted for C as your 1st choice, your 2nd choice (as long as it isn’t C) will now earn a fraction of a vote. If this sounds strange, just understand that it’s necessary to prevent the system punishing people for voting for popular candidates. If you vote for someone who wins early, your 2nd and 3rd choices shouldn’t suffer.

Remember that voters will behave the exact same way as they did in our last simulation, and for the purposes of this demonstration, that means the vast majority of C voters choose B as their second choice, and X voters the same with Y.

Y benefits from X’s excess votes, but it’s not enough. B’s 1st choice votes plus A’s excess votes are enough to cross the threshold, and B earns the 3rd and final seat.

Despite having the same results, the proposed system returns two Leaf winners and one winner from the Castle party.

What happened here?

You might be wondering why the election turned out so differently. One of these answers must be “wrong”, right? You can’t do a math equation twice, in two different ways, get two different answers, and they’re both correct. One of these has to be an error.

But this isn’t a math equation. Elections are much more subjective than many people think, and there are multiples ways to calculate winners, especially in elections for multiple seats. What is happening here is that the two systems ask slightly different questions. The current system asks, “how do the most voters rank their choices for these seats?” The proposed system asks “how can the council be most proportional to how voters ranked their choices?”

Let’s look at some graphs –

Under the current system, Castle voters are completely unrepresented, despite making up about a third of the electorate. In the new system, their representation is roughly proportional to their vote share, 1/3 of the seats for just over 1/3 of the votes, (38%, to be precise.) It also means that X, the candidate who came in 2nd in terms of first-choice votes, gets one of the three seats, instead of being totally snubbed.

But this also means that, despite making up a clear majority, the Leaf voters still have to work with Castle representatives. The Leaf voters, an indisputable majority of the city’s voters, showed their steadfast rejection of Castle policies by rebuking even their most moderate candidate. But now this minority interest gets a seat? Currently the Portland Charter doesn’t allow any candidate with less than a majority of the vote to be elected, but this system would let candidates with less than a third of the vote get elected!

Which is fairer? Ultimately, it’s a matter of philosophy, and one’s opinion about how a government is best run. Should a clear majority in favor of one party be interpreted as a mandate for unchallenged rule by that party? Or should legislatures look as similar to their electorate’s preferences as possible?

It’s not a question with one correct answer.

Why almost none of this matters

To those who skipped here from the top, welcome back. You didn’t miss much.

In the context of the City of Portland’s elections, almost none of this matters. This reform would only apply to elections where there is more than one seat in contention. This mostly means at-large seats in the City Council and School Board. But if Question 2 (Governance) is approved by the voters, that will eliminate all at-large seats on the School Board, and diminish the relative power of the at-large City Council seats. Add to this that the at-large seats are not ‘synced up’, Pious Ali’s seat will be up for election this year, April Fournier’s in 2023, and Roberto Rodriguez’ in 2024. That means for the foreseeable future, at-large seats will not be decided with this system. And even if two of these seats are ‘re-synced’ (purposefully or accidentally), pRCV results in a two-winner election tend to be less impactful than they are on elections with three or more winners. And there won’t be any at-large School Board seats if Q2 passes. And pRCV absolutely does not apply to district seats, where there’s only one winner. Unless this question is approved, but Question 2 is not, (an unlikely outcome), then the only elections this may apply to any time soon are for the (not unimportant but not terribly exciting) races for positions like Water District.

So, really, this question matters very little.

But in a bit of irony, one way that this system would have had a major impact is – the Charter Commission itself. If the candidates had been elected using pRCV, the slate of Commissioners would look very different. Still, it may be worth it just to make the constitutional change to allow proportional votes, overwriting the current Charter provision which prevents the election of candidates with less than 50% of the vote. This being said, one of the commissioners was opposed to this initiative so much that he filed a minority report against it, citing high costs of running complex elections. Instead he recommended a simpler, (and cheaper to manage), option for the city’s multi-seat elections: ‘approval voting’. This is a much more straightforward process in which voters mark all candidates that they would be happy with, and then whichever candidate is acceptable to the most citizens is elected. This also has the added benefit, per the commissioner, of favoring agreeable and moderate compromise candidates over minority firebrands.

~

Why might you vote in favor? – If you think that it’s important for elections with multiple winners to be as proportional as possible to citizens voting for them, even if it’s not a scenario that comes up often.

Alternatively – If you just want this annoying, unintentional restriction on elections implemented in 2020 by accident to be removed. I mean, that’s just housekeeping.

Why might you vote against? – If you conclude that proportional RCV is much too complex for the benefits it offers. It will almost never be relevant to Portland elections, and yet it will require much more spending on election infrastructure to ensure victors are correctly tabulated. Simpler voting methods, like approval voting, or a return to a modified first-past-the-post system, would do just as well for municipal elections with multiple winners.

Alternatively – If you think that actually, majoritarian voting is just fine. If a clique of candidates controls a majority of voters, they clearly have a mandate to enact their agenda without needing to accommodate minorities.

~

Next Section: 5 ~ The School Budget

Preface

Background ~ What is the Charter Commission?

1 ~ The Land Acknowledgement

2 ~ Governance

3 ~ Elections

4 ~ Voting

5 ~ The School Budget

6 ~ Peaks Island

7 ~ Police Oversight

8 ~ The Ethics Commission

Conclusion & Opinion

I think it may be useful to note that I support this reform even though it would have prevented my own election to the Charter Commission. It’s more important to me that we do the best possible job of representing the views of the electorate.

Absolutely, I hope nobody would have assumed otherwise. Thank you!

thank you Pat for correcting this problem.