The City Council’s chambers this past Monday, May 6th were packed full to speak on two pressing matters – the annual budget for Portland Public Schools, and the Council’s consideration of the Portland Museum of Art’s request to demolish the building at 142 Free Street, formerly the Children’s Museum of Maine. Though there would be a great outpouring of passion on both of these issues, particularly the latter, neither would see a final resolution. The schools’ budget will be voted on at the next meeting, per the two-hearing requirement, while the attempt to exempt the PMA’s building from Historic Preservation was delayed pending legal review.

Before either of these central items was addressed, however, the Council first had to dispatch a number of smaller issues. After reciting the pledge of allegiance, the floor was opened to allow comments from the public regarding items not on the night’s agenda.

General Public Comment

Unsurprisingly, first to speak was meeting jockey George Rheault, whose first concern was a foreshadowing of the historic preservation debate to come later. Claiming that the Boys and Girls Club in Portland had been buying up property in the West Bayside neighborhood as part of an expansion, Rheault requested that the city devote historic preservation protections and resources to this traditionally-deprived part of the city. He accused preservation advocacy group Portland Landmarks of being hypocritical in failing to give his neighborhood fair treatment.

Adam Sousa spoke next, asking the council to intervene in relaxing the street parking restrictions in Portland’s Downtown district. “Shifting parking spots every two hours is something that impacts Portland’s downtown workers negatively.” Sousa, who co-owns Portland Distilling Company, believes that this regulation most directly hurts workers, especially those in the restaurant industry like himself. Kylie Liberty offered comments to the same effect, expressing her fears of being “ticketed every two hours” during long work shifts, “accumulating up to four tickets in one day.”

Joshua Leonard, a director of a drug recovery program here in Portland and who had spent “eighteen years battling drug addiction,” urged the council to ignore any calls of shutting down recovery housing resources. He noted especially the impact of Maine’s housing shortage and the rise in “diversity” on the city’s recovery resources.

With no further comments on non-agenda items, Mayor Dion gaveled this period to a close and asked for announcements from the council.

Announcements and Proclamations

Councilor Bullett asked for the floor to pay respects to James “Jim” Neales, long-time member of the city’s Parks, Recreation & Facilities Department, who died on April 29th of this year. Jim also served as a recess monitor at Portland’s schools, taught extracurricular classes, and spent more than 26 total years as a city employee. Bullett, on the verge of tears, shared the experiences which her own children had with Jim. Councilor Phillips got up to offer her colleague a tissue, and once her short statement was concluded, Mayor Dion held a brief moment of silence.

The Mayor then noted that the municipal budget will be read at the May 20th council meeting.

Moving into routine proclamations, City Clerk Ashley Rand read into the record a celebration of the Maine Celtics “winning the first Eastern Conference championship in the history of the franchise.” Dion then recognized the 55th annual Municipal Clerks Week from May 5th to 11th, elaborating upon the essential role which the city’s administrators and clerks play, especially Ms. Rand and her office.

The City Clerk then proclaimed May 19th to 25th as Arbor Week, sharing a brief history of the event and the importance of urban tree coverage to Portlanders’ comfort and wealth. The Month of May was also recognized as both Building Safety Month and National Bike Month. Mayor Dion tapped Councilor Fournier, who herself is Native American, to read a recognition of May 5th as Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Day.

Licenses

Mayor Dion then stood to announce a change in how license-related orders would be handled in City Council meetings. In the past, business licenses for restaurants, lounges, bars, and other public establishments had been processed as individual orders, one after another. Each of these orders was afforded individually all of the procedural stages, including reading into the record, a public comment period, council discussion, and a separate vote. Given that these licenses are, typically, quite uncontroversial, only occasionally mustering substantial public or council discussion, the Mayor announced that this process would be greatly condensed. From now on, all license orders will be processed as a single consent item, taking all steps for all proposed licenses simultaneously. Dion affirmed that all comments would still be heard, (“it’s not like we’re going to ignore you,”) but he expected this to save a notable amount of time.

City Clerk Ashley Rand read, in one uninterrupted sequence, the licenses which the council was considering that night. These consisted of three routine “Outdoor Dining on Private Property” licenses for Mr. Tuna, at 83 Middle Street; Tandoor Indian Restaurant, at 88 Exchange Street; and Three Dollar Dewey’s, at 241 Commercial Street; and one “Class XI Restaurant/Lounge with Indoor Entertainment” license for Pizzaiolo at 360 Cumberland Ave, an existing restaurant adding alcohol service and entertainment.

Once these four applications were announced, the Mayor asked for public comment on any of the applications, and at first he thought there was none. “Proves my point,” he joked, before realizing that one (predictable) member of the public did in fact have something to say. “I spoke too quickly.” George Rheault had concerns about Pizzaiolo’s application for alcohol service, “There are residential families right across the street from this,” he said, noting that “our homeless neighbors frequent the convenience store” nearby, but that store closes at 9:00. Rheault worried that if Pizzaiolo will be serving alcohol later, that the presence of a “rowdy, more rambunctious scene” will worsen. “There’s an equity issue here.”

Trying to ameliorate Mr. Rheault’s concerns, the Mayor called forward Jessica Hanscombe, Director of Permitting and Inspections. Dion asked what form of public notice is given of license applications, to which she answered by saying notice is published on the city website and in the Portland Press Herald, but that no active solicitation of neighbors or anyone else is made by the city. Hanscombe took the opportunity to say, however, that her department does track statistics relating to disturbances at business sites, and that this can affect those business’ future applications and renewals, and could even lead to revocation by the council. The Mayor was satisfied by these answers, and the City Council unanimously approved the licenses.

School Budget

What followed was the first of two public hearings of the Portland Public Schools’ budget for Fiscal Year 2025. As the Mayor and City Manager West explained, public comments would be taken both that night and at the following meeting, (though one would not be allowed to speak at both,) and the council will discuss and vote to approve or remand the budget at the following meeting.

Multiple parents of students in Portland Public Schools (PPS) stepped forward to urge the council to adopt the proposed budget in full. Laura Rosen, parent of a 3rd grader, asserted that the budget “represents the floor” of what would be tolerable, and that “any reduction will cause much more harm to the district and our kids than it will benefit individual taxpayers.” May Lena, parent of a 7th grader, emphasized that the process thus far had been very open and transparent, “I’ve felt heard throughout the process.” She emphasized the costs which the great diversity of PPS’ student body bears, and how there should be no further cuts. Christina Knight, parent of a 2nd grader, likewise pleaded with the council to “approve the budget as it stands.”

Steven Scharf, another frequent attendee of council meetings and budget watchdog, broke the harmony. He claimed that the information the council included was full of “glaring errors” and omissions, failing to include the actual budget document and leaving much placeholder text (“appropriating 0.00 dollars to…”, etc.) in place. Scharf stressed that the entire process is deeply confusing to laypeople, and that the city is contemplating a baffling “ten million-dollar property tax increase. Ten million dollars.” He went on to object a number of line items, (“Do we really need a chef?”), and urged the council to restrict the School Board’s autonomy for budget decisions.

Audrey Cabral, Music Coordinator for PPS, spoke in favor of music programs at the city’s schools, which she claimed were being unfairly deprived. Noting that there were three visual arts teachers for every one music teacher, and that “we don’t have enough instruments,” she shared that prospective student musicians were having to be turned away. Cabral asked for additional funding for music.

Responding to some unrest in the balcony, Mayor Dion clarified that the meeting that night was not a hybrid meeting, and that no Zoom callers would be heard. With no further comments, he called the first school budget hearing to a close.

Floodplain Management

Before getting to what would be the dominant issue of the night, the council first (prudently) took up the much less controversial subject of floodplain management. Brandon Mazer, chair of the Planning Board, stepped up to introduce Order 181, amending the city’s Land Use Code to conform with state and federal laws and guidelines relating to managing land use in flood-prone areas. These changes were required to maintain the city’s qualification under the National Flood Insurance Program. This program, among other things, allows property owners to receive discounted rates for flood insurance. With a deadline looming for June 20th, the changes (which were recommended unanimously by the Planning Board) would have to be adopted (or modified, then adopted) in short order.

Though not as controversial as the PMA issue would be, a couple of comments were still offered on this order. George Rheault noted the significant expenditure of city resources which were required to produce these amendments, and asked whether it was fair for this all to be done for the benefit of a relatively small group of property owners in desirable parts of the city. He even intimated that Dion may be favoring these property owners, saying “correlation is not causation, but since our Mayor came on the scene, floods seem to be happening with a greater frequency around here.” Dion retorted with a quick “I apologize,” and Rheault kept it rolling with “You probably didn’t anticipate that you’d be King Neptune around here.” He went on to criticize the details of the plans, attributing the failures to “foot-dragging” and special interests. Once Rheault had concluded, Dion briefly noted that “I’d prefer Noah, over Neptune.” The crowd laughed at the exchange.

Thomas Scarrow, self-identifying as “one of the homeowners that Mr. Rheault is talking about,” was less breezy. He shared that the first time he’d heard about this process was from a postcard he had received three weeks prior, and “now we’re already at the second reading, when it’s too little too late.” He said he’d emailed the provided address on the postcard, Zoning Administrator Ann Machado, with his questions and concerns no fewer than three times, but that he hadn’t received a single reply. “This is a serious issue. When your home gets put into a flood zone, you can lose value by up to 10%. I just closed a year ago.” Agreeing with Rheault that there were errors with the maps, he asserted that according to federal guidelines his home was (admittedly, barely) outside the flood zone, yet it was being classified as within the zone. He asked for analysis and revisions to the plan.

Mayor Dion asked for a representative of the planning staff to step forward, asking whether the designations in the plans were open to reconsideration or revisions, and if so, under what circumstances. Ann Machado, the Zoning Administrator who had apparently failed to respond to Mr. Scarrow, rose to the podium. “I apologize I haven’t been able to get back to everyone who has emailed me,” she opened, before proceeding to explain that the maps had been created originally by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in 2017. A period of appeals had been allowed, but as of 2023, FEMA was no longer accepting such appeals, so there was little chance of any alterations. Machado further explained that many owners may have houses which aren’t technically in the flood zone, but which sit on property which does, partially, overlap. She briefly outlined the process for staging an appeal to FEMA, but warned that the costs would be significant and the chance of success slim.

Recently-elected Councilor Sykes spoke up, asking whether it would be possible to create some sort of fund for those affected by the sudden shift, but Corporation Counsel Goldman shot down this idea quickly. “The notion of spending public funds on private property is not permitted under state constitution.” He said he’d be willing to look into it, but held deep reservations. Sykes accepted this verdict, just noting that the city should be on the lookout for ways to help.

With no further discussion (other than a minor procedural amendment) the order passed unanimously. A brief recess was called before approaching the main course of the evening.

Portland Museum of Art vs. Historic Preservation

For a detailed look at the question which the City Council considered, read Historic Preservation and the PMA: A Guide to the (Actual) Question for the Out-of-the-Loop, published earlier on the Portland Townsman. This author serves on the Historic Preservation Board which adjudicated the issue in 2023, but has not directly played a role in the proceedings since.

With the rest of the night’s business wrapped up in just over an hour, the City Council would now spend the next three hours and change reckoning with the biggest issue of the night, the status of the structure at 142 Free Street.

Background

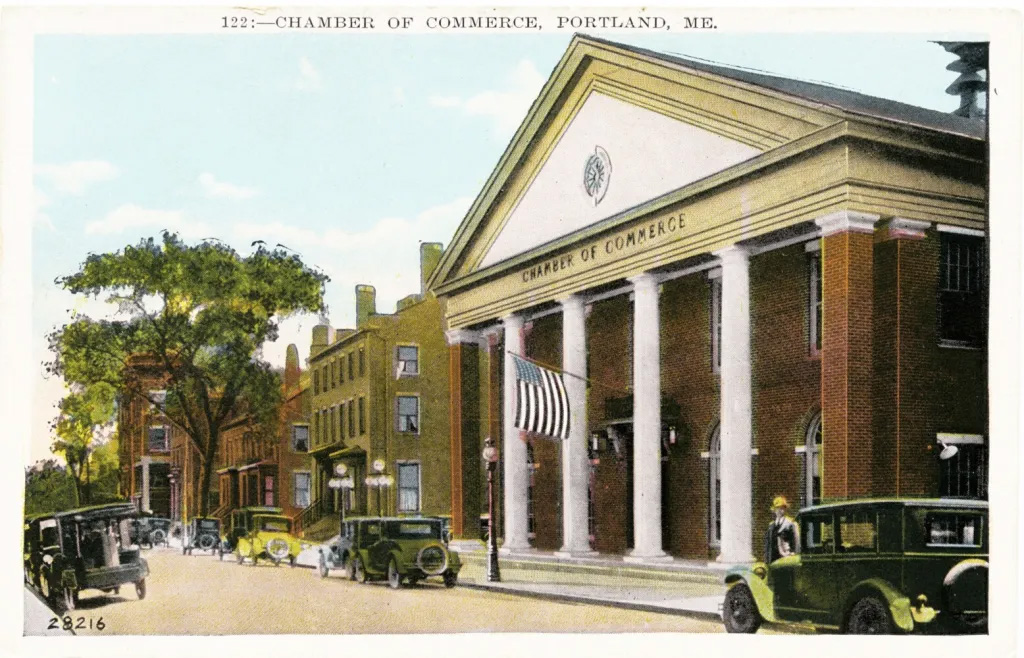

The Portland Museum of Art (PMA) acquired the building at 142 Free Street, best known as the former home of the Children’s Museum of Maine, in 2019. The Colonial Revival-style temple-like structure was originally built in 1856 as a theater, was converted to a Baptist Church, received a thoroughgoing remodel in the early 20th century by John Calvin Stevens in which it attained its current form, was the headquarters of the Portland Chamber of Commerce until 1991 when it became the Children’s Museum, and was sold to the next-door PMA as part of the Children’s Museum’s move to Thompson’s Point.

In 2009, the Congress Street Historic District was established, outlining a section of downtown Portland around the titular way to be protected by the city’s Historic Preservation (HP) ordinance. From the outset, 142 Free Street was classified as “contributing” to the historic district, meaning that it cannot simply be demolished. “Non-contributing” structures, which were built after 1960 or otherwise do not help to establish the visual and historical character of the district, are allowed to be demolished.

In 2022, the PMA announced its intentions to demolish the current 142 Free Street structure to make way for a grand new expansion to the museum, and held a contest with public input to choose the design for it. After the winning plan was selected from Lever Architecture, (based in the other Portland, in Oregon,) the PMA began the process of requesting re-classification from “contributing” to “non-contributing.” This process is fairly uncommon for such prominent buildings, and both the Historic Preservation Board and the Planning Board found (the former unanimously, the latter with one dissenter) that the red-brick structure met all the criteria to remain “contributing,” and thus barred from demolition.

Unperturbed by the rulings of the merely governing boards, the PMA’s directors and attorneys trusted that they would get a more flexible hearing from Portland’s legislative authority: City Council. After many months of preparation, the issue was finally set to be heard by the councilors, who would make the final decision whether to confirm the HP and Planning Board decisions, or whether to make an alternative finding of law, (or, as a third option open only to them, to consider some amendment to the HP ordinance itself.)

Presentation and Public Comment

After reconvening, Chair Brandon Mazer of the Planning Board and Kevin Kraft, Interim Planning Director, presented the facts of the case and the procedural history thus far. Kraft stressed that while the City Council would still be acting in a quasi-judicial capacity, they had final authority over the issue and were free to find differently from the boards. The Mayor then opened the floor to a flood of public comments, (presumably to FEMA’s chagrin.)

Mark Bessire, Director of the PMA, was the first to speak. He focused on the museum’s need for more space, citing the “exponential” and “unprecedented growth” of the museum, “we’re running out of room for people, for events, and for art.” Bessire also noted the boost it could give to the downtown, and boasted that the architecture firm they had selected was “one of the few firms in the world led by women of color,” and who had consulted with a “Passamaquoddy advisor” on the design to “honor the Dawnland.” He did not address the legal question, but urged the Council to make a holistic ruling.

Ringing a very different note, Elizabeth Boepple next rose to the podium, an attorney of Murray Plumb & Murray representing Portland Landmarks. Boepple is also the former chair of the Portland Planning Board, and opened by telling the councilors “I know the position you’re in… the pressures which can come with reviewing requests from an applicant such as the PMA. That is, an applicant who seeks to turn the required legal analysis into a PR campaign.” Cutting through the noise, she warned the council “You must apply the law.” Boepple reiterated the findings of both public and private bodies, and told the council there is little wiggle room, that 142 Free Street is clearly contributing. She also accused the PMA, as many throughout the night would, of “clouding the underlying legal issue.”

Tae Chong, former City Council member, said that what the issue is fundamentally about is the “empty building which has been vacant for five years sitting on a large parking lot.” He continued that, just as a conservative supreme court may view the law differently than a liberal one, so too can the City Council see differently to the Planning Board. Carol De Tine spoke next on behalf of Portland Landmarks, a private group which advocates for historic preservation in the city. “We shouldn’t even be here. You never should have been put in this position. This is not a popularity contest,” she began, emphasizing again the importance of the basic legal question and dismissing the surrounding discourse. “We are here because one of us has chosen to ignore the [HP] ordinance, and the other is fighting to uphold it.” She urged the council to not overturn the boards’ decisions. Bruce Roullard, President of Portland Landmarks, accused the PMA of asking for special treatment, and spoke on the importance of historic preservation to Portland. He reminded listeners of the large-scale demolitions of historic sites which took place in the mid-20th century and inspired the modern HP process, noting they too had been motivated by progress.

Chris Rhoades, co-owner of the similarly historic Time & Temperature Building on Congress Street, raised an issue which seemed to take many off-guard. The ownership group which he is a part of is attempting to convert much of the T&T Building into affordable housing, and is reliant on historic preservation tax credits from the federal government to enable this. But, Rhoades claimed, if the Council was to so flagrantly compromise the integrity of the Congress Street Historic District, (which his building is also in,) the federal government may find that the CSHD fails to meet their criteria for such tax credits. Scott Hanson, former Portland Planning Department employee and consultant who helped establish the HP ordinance, warned the T&T group of this exact scenario; Hanson would later give comment at the meeting denying any ambiguity in 142 Free Street’s classification. A Press Herald look into the issue has shown how inconclusive the issue really is, but this would inflame the discussion for the rest of the night. The National Park Service, which manages the credits, has yet to give word.

Barbara Vestal introduced herself as having been Chair of the Planning Board when the HP ordinance was drafted and passed in 1990, and who personally worked with consultants to establish its provisions. She joined the growing chorus of those who saw the issue as a clear-cut matter of law which could only plausibly be applied in one way, the way which the HP and Planning Boards found. Sean Turley, another Murray Plumb & Murray attorney representing Portland Landmarks, further illuminated the legal predicament, (“for which the PMA is fully responsible,” he added.) He reminded the council that the PMA knew the building was classified as “contributing” when they bought it, (how might this have affected purchase price?), and the museum “now asks the council to save it from the crisis that the PMA itself created.” Turley reaffirmed that the question before the council is not a policy question, weighing competing priorities, but rather the dry application of existing law to a clear-cut case. “It wasn’t a close call then, and it’s not a close call now.”

George Rheault returned to the podium condemning the “misinformation [from] the Greater Portland Landmarks lobby.” He cited a National Park Service bulletin which confirmed the ability of municipalities to reclassify structures, as the PMA was requesting, and called the legal arguments which had been made against the PMA or concerning tax credit cancellations as “absolutely hogwash.” Rheault began to discuss past instances of the city violating procedure relating to re-classification, but Mayor Dion directed him to stay on the topic at hand, to the commenter’s great frustration. The two men soon began talking, even shouting over one another. “Mr. Rheault, you actually do enjoy this, and I appreciate that,” the Mayor said, “the animation is welcome… I’m trying to suggest-” the two began arguing over one another again. As Rheault continued to speak over the Mayor in reference to past incidents, Dion remarked “Shut him off. Shut him off. You’re done,” he slammed the gavel, “You’re out of order.” A defiant Rheault refused to stand down, “You’re basically attacking the content of my remarks, which you’re not allowed to do. There is a first amendment to the constitution, Mr. Mayor, and you are violating it.” After continuing to speak for a while longer, to the apparent discomfort of those audience members nearest him, he was told once more by Mayor Dion to stand down for being off-topic and out of order. Rheault still did not conform, accusing Historic Preservation Board chair Robert O’Brien of lying about his past actions, and the city administration in general of double-dealing, “And I’m the problem?” He then walked away from the podium. “Thank you for your dissertation,” the Mayor quipped.

Robert Kahn, speaking against the museum’s appeal, opened his comments with a colorful remark. “Replying to the conflicting statements and hyperboles coming from the PMA is like being a mosquito at a nudist colony. Where to begin?” He echoed the opinions of the Portland Landmark attorneys in recognizing the clear legal question, and further speculated that the museum’s directors were trying to dig themselves out of a hole. “A board like that, [the PMA’s,] in my experience, doesn’t like to admit a mistake.” Alex Jaegerman, a former Portland planning staff member, recalled his experience with the HP ordinance as it was being drafted and passed, and said the building at 142 Free Street clearly meets the criteria as being “contributing” by any reasonable metric.

A woman with connections to both the museum and Portland Landmarks and who introduced herself as “Key Open-Eye” expounded upon the intrinsic subjectivity of historic preservation. She also responded to a common implicit criticism – that the PMA shouldn’t have held the design contest before getting re-classified – by noting that the PMA was acting with the advice of city staff in doing so. She seemed to ultimately favor re-classification. “Chloe” took an opposing view, emphasizing the environmental costs of demolishing and re-building structures instead of re-using existing ones. “This will be the third building the museum has demolished and sent to landfills. Can the city afford this much waste?”

Eileen Gillespie, speaking on behalf of the PMA’s executive committee, tried to clarify the museum’s legal position. “We believe that 142 Free Street, as it stands today, should never have been declared ‘contributing.’” She did not much further elaborate on this legal opinion, and echoed her colleagues’ arguments based rather on economic and artistic investment. Scott Simons, opening with an optimistic take, called the night’s discussion (and prior discourse) “the best dialogue there’s ever been” about historic preservation he’s seen in 35 years in Portland. He asked all involved to remember the humanity of all sides, and spoke in favor of the PMA’s project, encouraging the council to take a more wide-eyed and far-sighted view than the narrow scope the boards must take.

Chris Newell, a member of the Passamaquoddy tribe and partner of the architects for this project, shared his perspective on the indigenous character of the project. “My role with the [Lever] team was literally to teach them about the history of something that goes back further than the last 200 years, which is the state of Maine, but the last 12,000 years of Wabanaki history and stewardship of this land.” Newell stressed how seriously the architects took his teachings. “Museums are colonial artifacts,” he continued, “preserving history in the way that we do now, with museums, with art, these are artifacts of colonization. We have the opportunity with this project to create a new artifact of colonization that is inclusive, not exclusive or extractive, of Wabanaki people.”

Debra Andrews, former Historic Preservation Program Manager for Portland, stated that she knew intimately the procedures and details of the HP ordinance and how it applies to the Congress Street Historic District. She reviewed the criteria for establishing whether or not a building is “contributing,” and focused on one in particular – whether or not the building retains its “integrity” as a structure. “Does 142 Free Street still look essentially the same as it did when John Calvin and John Howard Stevens completed their comprehensive redesign in 1926? Clearly it does.” She rebutted the arguments made by the PMA that various minor alterations made in the later 20th century compromise this integrity, and confirmed the good condition of the building as a whole, noting that the PMA has provided no evidence of any loss of integrity.

Mary Costigan, an attorney representing the PMA, stepped forward to try and “talk about the law” from the PMA’s perspective. “There’s been some discussion about how the museum isn’t ‘talking about the law.’ I don’t know about you, but I have many artists friends who don’t like to ‘talk about the law.’ So it’s my job to talk about the law.” She informed the council that during the Planning Board’s hearing, the whole process had to be delayed so that they could reach a conclusion on an important legal factor – whether or not the city’s Comprehensive Plan (a programmatic document passed by the Council) factored into the board’s decision. Though the board’s counsel returned a negative verdict, telling members to focus only on the ordinance, one member (Marpheen Chann) disagreed and voted in the minority. “It’s not clear,” Costigan explained. She urged the Council to take this minority position and make a decision incorporating the Comprehensive Plan.

Many more commenters spoke on this issue, and those not summarized above split fairly evenly – by this author’s count, precisely evenly – between those who supported and those who opposed the PMA’s requested re-classification. A majority of those who supported the PMA had one thing in common: they worked for the PMA. Many employees of the museum had come out to support the project, speaking not only as workers but as people passionate for art and curation. There was much talk of the bold new vision, informed by diverse and progressive perspectives, which the new building could offer, and general skepticism that preserving old buildings in amber contributes much to the city. They were all united, primarily, by the vision which the PMA was offering.

Those who came out against the re-classification were somewhat more varied. Some, like the bulk of the attorneys who had spoken, focused on the simple question of law; stripped of the surrounding noise, the presumptive answer to the legal question did appear to be that the building was “contributing.” Others cast doubt on the museum’s motivations, and feared that if this wealthy organization can evade the HP ordinance, that others will surely follow. Still others were sincerely passionate about preserving the history of the city as its written in brick and mortar, and dreaded the thought of demolishing the lovely old building.

After about one-and-a-half hours of public comments, Mayor Dion gaveled the period to a close.

Council Deliberations

Before opening the floor to the councilors, Corporation Counsel once more took the time to explain the legal criteria which the council was being asked to evaluate. “To determine the building is non-contributing, the City Council must find… that the building does not contribute generally to the qualities that give the district cultural, historical, architectural, or archeological significance.” He noted also that the draft order he prepared for the council was an approval of the boards’ findings, a decision against the PMA, because the HP and Planning Boards made factual findings which he could base this order on. Despite this, Goldman reminded the council that they are not obligated to agree with the boards, and could make their own factual findings and reach a separate conclusion.

Councilor Bullett then asked the Mayor if the council could take a brief recess, but as Corporation Counsel had been speaking, he instinctively replied “absolutely.” When everyone realized that the attorney had assumed the Mayor’s role just then, the room erupted into laughter. The council did take a recess, and then moved into deliberations.

Councilor Trevorrow spoke first, offering an amendment to the order sponsored by herself and Councilor Sykes to designate the 142 Free Street as non-contributing, per the museum’s request. This amendment was a very minimalist reversal, changing little in the order besides the polarity of the outcome. Notably, and this would become important later, it did not make any substantial new findings or interpretations to support its conclusion. Trevorrow noted that a brief statement of justification had been added to the order’s language, but otherwise spoke only very briefly about her amendment.

Councilor Sykes next asked to speak to what she considered the “crux” of the issue, “the building’s integrity.” While this term is conventionally (and statutorily) understood to refer to the literal soundness of a building’s structure, Sykes more broadly interpreted the term to refer to the overall significance of the site. She cited material written by Debra Andrews as HP Program Manager which stated that if a building’s “integrity” is compromised, then it may require a reclassification to noncontributing. Sykes believed that, while “there is a lot of attachment to this building,” the council should consider the site’s (broadly-interpreted) “integrity” to be compromised and re-classify.

In response to this novel reasoning, the Mayor called Planning Board chair Brandon Mazer to the podium to clarify the issue. “On the issue of integrity,” Dion asked, “what kind of showing had to have been made in order for the property to have received that designation?” Mazer replied that the HP Board and its associated staff reviewed the building’s integrity and significance and did not find any such compromise; nor, indeed, had integrity even been a major topic of discussion. “At the time, and there is some confusion here, they [the PMA] did not question the integrity of the building… that issue was ceded.”

Kevin Kraft, of the Planning Department, stepped forward to add some nuance to the chair’s statement. “The Historic Preservation Board did review the integrity standards and the applicant did make an argument for that,” he clarified, explaining that initially the PMA had conceded historic significance to the structure and was arguing that the building’s integrity was compromised. After the HP Board found inadequate evidence for their claim, the PMA’s arguments shifted towards denying that the building ever possessed sufficient, continuous significance. Both staff and board members seemed somewhat unsure of the procedural history’s precise parameters.

Letting the men at the podium loose, Mayor Dion turned to Councilors Sykes and Trevorrow. “What facts,” Dion asked, “are you going to use to support the integrity assertion? Because this record is going to go some place beyond here.” The Mayor was likely referring to the all-but-certain lawsuit which would follow whatever the Council decided. “This is beyond the structural condition, integrity of the building,” Sykes answered, “this is about the integrity of the building as a historically-designated building.” She proceeded to argue that the building’s renovation in the 1920s, conducted by the Portland Chamber of Commerce, fatally weakened any “authenticity” the building possessed. She also argued the minor renovations which the Children’s Museum made in the 1990s, such as adding a cupola to the roof, also compromised its significance. “It lacks integrity as a building to preserve.”

Mayor Dion next called on “Councilor Williams,” while he pointed to Councilor Phillips. “I can be Councilor Williams if you want me to be,” Phillips joked to the Mayor, “just tell me who she is, where she lives, does she have a big bank account? That’s really what I’m interested in knowing.” The room roared with laughter as Dion profusely apologized for the slip of the tongue. At any rate, she opted to step back and allow Councilor Trevorrow to speak before her.

Recalling the advice she had received from an attorney while serving on the Charter Commission, Trevorrow said that “nothing is actually illegal until it’s ruled on by a judge. Until then, all you have is competing legal opinions.” She recounted her meeting with the project’s architects, and said that she really believes the proposed building would work towards goals of diversity, equity, inclusion, and sustainability. Trevorrow reasoned that, as the City Council, they could rule on the issue quite freely, and urged her colleagues to favor the vision of the PMA.

Taking her turn, Councilor Phillips took a different tone. “No one in this room doesn’t want to see the Portland Museum of Art succeed, of course we want to see them succeed,” she prefaced, before pivoting and announcing “I believe that it [the building] is contributing.” Stressing the hours she had spent poring over the relevant facts and laws, Phillips said the Trevorrow-Sykes amendment caught her off guard, and she didn’t understand their arguments. “I can’t make a decision when I’m handed a piece of paper five minutes before a vote… I do not support this amendment.”

Councilor Fournier, following up on this harsh rebuke, tapped into her indigenous vocabulary to weigh up the issue. “I’m always planning for the next seven generations,” she said, “I always carry my ancestors with me, who came before me.” Fournier broadened the scope of the discussion to cover the entire edifice of historic preservation as a concept, asking “Whose history are we preserving?” She recalled the proclamation she read earlier in the evening regarding Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, and shared that “When I look at this building in question, it’s a style of building which is actually not comfortable for me.” She recognized that the council did have to base its decision on current ordinances, but “I would also offer, in my mind, that Historic Preservation itself and the ways in which things are classified are subjective, and based on who is telling the story of a community.” She signaled her support for the amendment.

Mayor Dion joined Councilor Phillips both in commiserating over the many hours spent reviewing this case and the final position they’d take towards the amendment. “I appreciate both councilors trying to turn this into an affirmative statement,” Dion said, “but there’s some assumptions here that I won’t be able to work with tonight.” He pontificated for a period on the perennial debates between “law and architecture,” and said he believed that there are areas of compromise to be found. The Mayor’s ultimate perspective, however, was that he understood his position as being tasked with reviewing the findings of the HP and Planning Boards and determining whether or not they erred. Since he believed their decisions to be rational, he’d vote to uphold them.

“It’s really an unexciting administrative process,” the Mayor stated, “Was procedure followed? Was there reasonable evidence for them to draw the conclusions that they made?” Despite the apparent simplicity of the question, he shared that he’d been inundated with passionate correspondence on the topic. Regarding the pro-PMA messages he received, “it’s almost as if there’s an underlying recognition that ‘The law’s not in our favor, so let’s talk about outcome. Let’s talk about glitter, let’s talk about future.’” He noted likewise that many of the pro-preservation comments were similarly hyperbolic. In the light of all this discourse, Dion felt he had no alternative than to trust the judgment of the HP and Planning Boards’ near-unanimous decisions. He suggested at last that if the preservation ordinance is inadequate, it should be considered for more in-depth reform.

Legal Concerns About the Trevorrow-Sykes Amendment

Interrupting the councilors’ speeches, Corporation Counselor Goldman raised a concern he had acquired regarding the Trevorrow-Sykes amendment to re-classify the property. “The council tonight is acting in a different capacity than it usually acts, it’s acting in a quasi-judicial capacity,” meaning that the body had to make findings of fact and reach a verdict applying the law-as-it-exists. Goldman informed the council, if they didn’t already know, that no matter what they decided, there would almost certainly be a lawsuit to overturn that decision by either the PMA or by the pro-preservation allies. This means that whatever the council decides, what they decide will be reviewed by a court, and so it must be adequate as a quasi-judicial verdict, lest the council be found to be abrogating its duties. He asked the amendment’s sponsors to “give me an opportunity to put together a decision that would, hopefully, stand up on appeal, that would have facts which support the applicable criteria… and support the determination about whether the property is non-contributing or contributing.” If the council listened to his advice, they would withdraw the amendment, postpone the order, and re-consider the issue at the next council meeting, which is on May 20th.

Councilor Sykes did not take this dry announcement lightly. “This is a highly irregular situation,” she began, “We, as a council, are the final authority on this. And we’re being asked to wait for a legal opinion before we render that authority?” She disagreed with the conclusion that her amendment was an inadequate basis for a conclusion, and criticized Corporation Counsel and other city staff members for not taking her amendment seriously. Trevorrow, Sykes’ co-sponsor, more coolly suggested a procedural path which would involve a vote on her amendment, but only with the aim of giving Corporation Counsel guidance as to how the council sees the issue. Some wrangling over the details of Robert’s Rules followed, and the issue was set aside temporarily to allow other councilors time to speak.

“Deterioration,” “Logical,” and “Integrity,” were the three key words identified by Councilor Bullett, who noted that last term as having “many different definitions.” Instead of focusing on the legal issue, Bullett tried to focus on simple practicality, sharing at length an email from the previous owner of the building who had struggled for so long to sell it. She also named other prominent groups, such as the Chamber of Commerce and Roux Institute, which supported re-classifying the building as non-contributing. “To me, that’s really, really strong community support for changing the classification.”

Councilor Rodriguez kept his cards close to the chest regarding the object-level question, but he commented on the procedural path which the council was taking and suggested that they all wait and see what Corporation Counsel would return with. Councilor Ali, similarly, suggested that the group allow for the attorney to come back with more detailed findings, and also did not reveal his underlying preferences. Sykes and Trevorrow both made spirited arguments in favor of moving forward with their amendment immediately, but did not seem to carry much support.

In the first words she had said all evening, Councilor Pelletier of District 2 declared “I’m confused.” She, the Mayor, and Corporation Counsel tried to riddle out the details of the procedure for many minutes. After this concluded, and after multiple councilors indicated that they’d be happy with a postponement, Councilor Trevorrow offered “I’m willing to withdraw the amendment.”

“I’m not willing to withdraw the amendment,” Councilor Sykes sharply retorted, demanding that the council take action that night. She stood alone, however, and the amendment was deemed (through a somewhat confused process) withdrawn. Trevorrow asked why the ‘default’ motion prepared for the council, to confirm the Boards’ findings, was adequate to stand up on appeal, but her amended motion, to overturn the findings, was not. Goldman explained that the HP and Planning Boards had made adequate findings of facts themselves, and so the City Council could use those if they agreed; on the other hand, if the Council disagreed, then they’d need to supply their own findings.

Councilor Phillips made a final argument for confirming the boards’ findings, citing the rich history of historic preservation and recovery in Portland’s recent past, but to no avail. The council voted to postpone the order with 7 in favor and 2 opposed. Those two councilors who dissented did so for opposite reasons, with Phillips on the pro-preservation side and Sykes on the pro-reclassification side.

Almost instantaneously once this vote was confirmed, the council moved to adjourn, ending the late-night and fiery meeting with an anticlimax.

Ashley D. Keenan – Ashley is an editor of the Portland Townsman, with work focusing on the mechanics of local government and housing policy, and also a member of Portland’s Historic Preservation Board. You can reach Ashley personally at ashley@donnellykeenan.com

An excellent summary of the meeting and the comments on both sides of the question – focusing on the division between, on one hand, emphasizing the actual issue of adhering to the legal question vs. attempts to obscure it by re-directing attention to the Museum’s “bright, shiny object.”

As to Councillor Trevorrow’s statement that “nothing is actually illegal until it’s ruled on by a judge”: if you’re walking down the street and someone comes up behind you, hits you on the head, and runs off with your backpack, is the Councillor saying that that’s not “actually illegal” conduct, pending a judge’s ruling? As to Councillor Sykes’ objection to Corp Counsel’s review of the amendment to assess its legal viability: who foots the bill for litigation if the City is party to a lawsuit? Does the Councillor not care if the taxpayers are on the hook if a poorly crafted amendment costs the City money? To my knowledge, neither she nor Councillor Trevorrow is an attorney, nor does either have the legal background to draft a sound (in substance and procedure) enactment that would hold up in court. Why isn’t she willing to work collaboratively with City staff instead joining with Councillor Trevorrow to try and shove a questionable amendment through for a final vote at the last minute – obviously surprising other Councillors, and clearly maneuvering to foreclose public comment?

Pages 126 – 129 from the public comment file completely undercut Ashley’s self-serving characterization of the 1992-1993 Children’s Museum renovations as minor (and that characterization allows Ashley to attack the basis for Councilor Sykes decision which was very legitimate and well-founded even if reasonable people can disagree with that): https://portlandme.portal.civicclerk.com/event/6488/files/attachment/22437

The fact that Ashley and her HPB members never wanted to confront is that you can drive a truck through the standards of classification (because it would expose the foundation of most of Portland’s “preservation program” as being about gentrification, real estate values and politics rather than any truly objective professional standards).

What is funny is that the massive “eye-of-the-beholder” subjectivity here was allowed to work BOTH ways in the case of certain projects which turned “contributing” buildings at 34 Spruce Street (2020) and 183 Brackett St (2012) into demolition victims, but suddenly, because Greater Portland Landmarks and its donors are heavily invested in the John Calvin Stevens myth-making, they refuse to let it work BOTH ways here.