Ashley Keenan is a member of the Historic Preservation Board. The following article does not in any way represent the views of the board as a whole, or any of its other members.

This Monday, the City Council will be asked to make a final decision on the status of 142 Free Street, the former site of the Children’s Museum and Theatre of Maine. Is the building which stands there today a historic building protected by the city’s Historic Preservation Ordinance, as the city has so far held? Or should it have always been considered as merely incidental? Should, in fact, the ordinance be changed?

The Portland Museum of Art, which owns the building, has been asking the city to reclassify the building and remove the restrictions which historic buildings like this are subject to, arguing that it never should have been classified as such in the first place. The Portland Museum of Art (PMA) has already unveiled plans for the expansion it wishes to build in the Children’s Museum place, and has staked its hopes on the city agreeing with its arguments.

There’s been no shortage of media coverage on the controversy, which has attracted passionate comment on both sides of the issue, but the question actually being asked is somewhat lost in a sea of context. Questions about architecture, objections to layoffs, concerns about million-dollar donors, accusations of stagnancy, fears of insolvency, aspirations to diversity, and other intertwined topics are interesting, and these should be given their due weight. Nevertheless, there’s a risk that these controversies, which are ultimately secondary to what the City Council is being asked to consider, may obscure the actual question at hand.

Those background issues will not be discussed further here. Instead, what follows is a guide to understanding the (in fact rather technical) question at the heart of the controversy, cutting through (as much as is possible) the web of prejudices and interests surrounding it. No prior knowledge of the obscure world of local politics is required. Armed with the basic facts, residents can incorporate as much of the surrounding context as they deem appropriate and reach their own conclusion on this historic debate.

First, a brief history of the building and of the issue.

A Brief History of the Theater/Church/Chamber/Museum

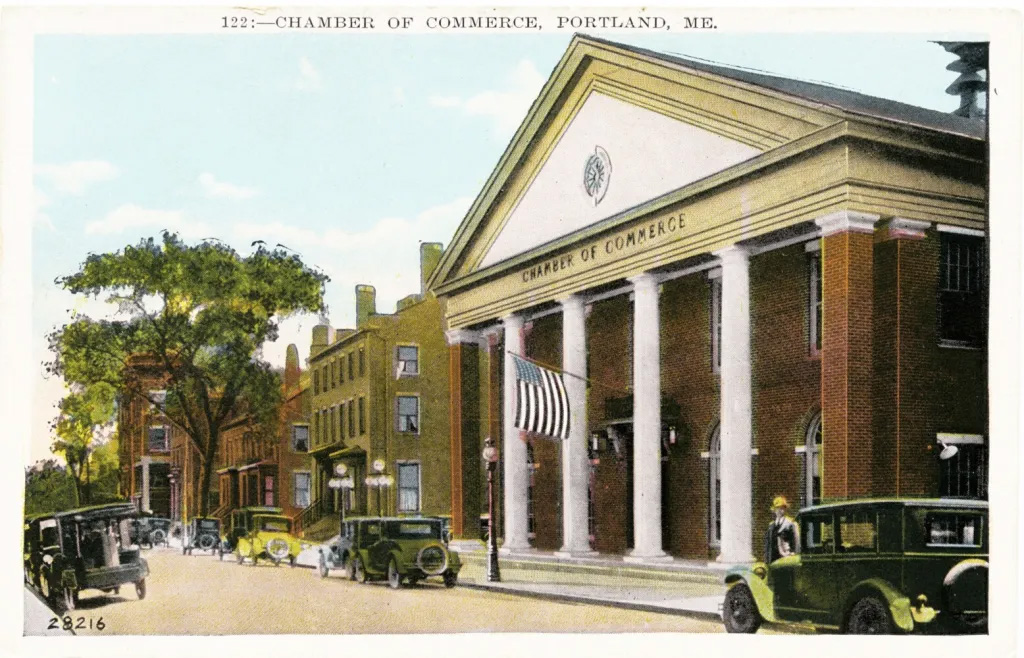

The building at 142 Free Street was originally built in 1830 as a theater, but would have been unrecognizable in appearance today. In 1836 it was purchased by the Free Street Baptist Society, which renovated it into a church. The building then, too, little resembled its modern iteration, and included (for a time) a very prominent spire atop its steeple. While the spire eventually came down, the building remained a Baptist church until 1926, when the congregation merged into what would eventually become the Williston-Immanuel United Church. The Portland Chamber of Commerce, purchasing the building, saw to it that the temple to God was fittingly remodeled as a temple to prosperity and thrift.

This renovation, which was a complete visual overhaul of the building, is key to the PMA’s claims. Designed by notable local architect John Calvin Stevens, the new exterior was a sober, temple-fronted design in the Colonial Revival spirit, white columns contrasting against red brick walls. The exact timeline of when this transformation was fully complete appears to be somewhat muddled, but it had certainly taken on its current form, more or less, by 1958. (Note that year, 1958.) A number of minor alterations were made, mostly to the interior, over the next several decades by the Chamber.

Then, in 1991, the site was sold to the Children’s Museum of Maine, which undertook extensive interior renovations but only minor alterations to the exterior. Even if minor, however, the alterations to the facade and addition of a cupola would have, if made today, required approval from the city’s Historic Preservation process. As it was, the Congress Street Historic District was not established until 2009. When Portland did establish this district, the Children’s Museum was classified as “contributing” to its historic fabric. This classification, the PMA now contends, was made in error, and the building should have initially been ruled as “non-contributing” to the historic district.

At last, in 2019, the site was sold to its current owner, the Portland Museum of Art. The Children’s Museum had been planning to relocate to Thompson’s Point, and the PMA had been looking for opportunities to expand, so the sale constituted a clear “win-win.” The PMA, however, soon decided that the current building would not be adequate for its ambitions, and in 2022 it began raising awareness (and money) for its plans to demolish the old building and construct something new. In June of that year, a contest was announced for architectural design firms to submit proposals for the new building, and in January 2023 the winner was announced. Lever Architecture, based in the other Portland, in Oregon, heavily emphasized the inspiration they took from Maine’s indigenous heritage in their design.

With money being raised and a design in hand, only one obstacle yet remained for the PMA to realize its plans: the “contributing” status of the building currently on their land.

But what does it actually mean to be “contributing”? (Or “noncontributing”?) What is this all based on? Why can Portland prevent the museum from demolishing the building, and what options does the PMA have? Was the original classification actually a mistake?

These technical points, rooted in the details of the often-misunderstood Historic Preservation ordinance, are necessary to grasp the question which City Council is being asked to decide on.

The Question

The question at the heart of this process has two halves. The first half is a strictly legal question, applying the law as it already exists to a fact pattern, while the second half is a much more open-ended question, subject to the judgement (and creativity) of the City Council. The question can be summed up as –

First, was the decision to classify 142 Free Street as “contributing” to the Congress Street Historic District in 2009 made in error?

And, if not, should the Historic Preservation ordinance be amended?

The second half of the question, concerning what the council’s options may be in amending the ordinance, will be set aside for the moment. Let’s examine the first half of the question, which simply applies the law as it exists now to the case.

In order to adequately answer the first half, one has to know what the Historic Preservation ordinance is, how it restricts owners of historic properties, what it means to be “contributing”, which properties are supposed to be “contributing”, what the Congress Street Historic District is, and how the implementation year of 2009 matters.

The Historic Preservation Ordinance

Chapter 14 of the Portland Code of Ordinances is the “Land Use Code,” which governs what buildings can be built and how they can be used in different parts of the city. (These parts are called “zones,” and it’s why this is also known as the “zoning code.”) Section 17 of the Land Use Code is titled “Historic Preservation”, and this section is colloquially known as the “Historic Preservation ordinance.” When people refer to the Historic Preservation ordinance, or “HP ordinance,” they’re referring to this section, which can be found here at page 287.

Fortunately, one doesn’t have to read the entire Land Use Code – or even this entire section – to understand what’s going on with 142 Free Street. The thrust of the HP ordinance is quite simple; as the residents of Portland have felt strongly about preserving the historic character of the built environment, the city can designate individual sites or entire neighborhoods as historically significant. By doing so, the buildings and land which are designated this way are subject to additional oversight and restrictions so as to not allow this historic character to be damaged.

When individual sites are recognized as historic, they are called “landmarks,” but 142 Free Street is not a landmark, so we don’t need to delve any further into that.

When a whole area is recognized as historic, a “Historic District” is created. Today, Portland has twelve Historic Districts, which run from the iconic Waterfront (Old Port) Historic District recognized in 1990, to the most recent, the Munjoy Hill Historic District established in 2021. Each district has a unique description which attempts to capture the character of the area, and these descriptions are what proposed alterations, constructions, and demolitions are measured against. 142 Free Street is within the Congress Street Historic District, which, as mentioned previously, was established in 2009.

Contributing vs. Noncontributing

All buildings are subject to restrictions within Historic Districts, but there are two classifications which establish the basic division within the districts: “contributing” and “noncontributing” properties. The law defines these terms as follows –

Contributing: A classification applied to a site, structure, or object within a historic district signifying that it contributes generally to the qualities that give the historic district cultural, historic, architectural, or archaeological significance as embodied in the criteria for designating a historic district.Noncontributing: A classification applied to a site, structure, object, or portion thereof, within a historic district signifying that: 1) it does not contribute generally to the qualities that give the historic district cultural, historic, architectural, or archaeological significance as embodied in the criteria for designating a historic district; 2) was built within 50 years of the date of district designation unless otherwise designated in the historic resources inventory; or 3) where the location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, and association have been so altered or have so deteriorated that the overall integrity of the site, structure, or object has been irretrievably lost. A portion of an otherwise contributing or landmark structure may be determined by the Historic Preservation Board to be non-contributing if it meets one or more of the above conditions.Put more crudely, a building is “contributing” if it’s part of what makes the district historic, and “noncontributing” if it doesn’t.

When the Congress Street Historic District was established in 2009, the initial report included 142 Free Street as a “contributing” structure. Once again, the Portland Museum of Art today claims that this was decided in error.

One detail which the eye may have glazed over in the “noncontributing” definition is worth paying attention to –

“a site… built within 50 years of the date of district designation”The Congress Street Historic District (CSHD) was designated in 2009, meaning that the ‘end point’ of historic character for the site is considered, by default, to be 1959. By coincidence, this is just one year later than 1958, the year by which it is broadly agreed that 142 Free Street assumed its modern form.

The building had not been totally untouched since 1958, however, and underwent some renovation in the 1990s when the Children’s Museum purchased it. Whether these alterations constitute the “irretrievable loss” described by the HP ordinance is part of what the City Council will have to decide on Monday.

In any case, though most of the buildings in the CSHD were (and remain) classified as “contributing” to the historic fabric, there are plenty of exceptions. Examples of buildings in the CSHD of both kinds have been selected below –

While there’s clearly a great variety of styles in both the “contributing” and “noncontributing” structures, it doesn’t take a scholar of architecture to sense a clear distinction between the two sides. Which side 142 Free Street falls on will, again, be up to the City Council on Monday.

No Way Out

The PMA’s representatives have stated they believe 142 Free Street ought to be considered “noncontributing,” and that the site should never have been classified as “contributing” in the first place. If the City Council were to agree with their convictions, it would also be conducive to the PMA’s aim of demolishing the old building and erecting a new, modern wing.

The reason why the distinction between “contributing” and “noncontributing” is so important to the PMA, and many other property owners, is that a “noncontributing” property is subject to very few Historic Preservation-related restrictions. “Noncontributing” properties remain part of the district, and are still subject to some oversight to ensure nothing too disruptive is built, but property owners have no obligations to preserve “noncontributing” structures.

Owners of “contributing” properties, on the other hand, face much more significant obligations and restrictions. The key issue, from the perspective of the PMA, is that ”contributing” buildings may not be demolished. “Contributing” buildings can be substantially altered, expanded, and even modernized with approval, but if a building is classified as “contributing” then the owner is not entitled to destroy it.

There is only one exception to this rule, and it hardly can even be considered. Per 17.7.9(A) of the Land Use Code, “any applicant seeking demolition of a… contributing structure must apply for a Certificate of Economic Hardship to the Board of Appeals.” While this may sound reasonable, “economic hardship” doesn’t simply mean that the owner would suffer a lack of profitable use, it’s an extremely strict standard. According to 17.9.2(A), such a certificate can only be granted if failure to do so would “result in the loss of all reasonable use of the structure.” Anything short of the building falling into a sinkhole would be unlikely to meet with success, and this is even before considering the American Gladiator-esque bureaucratic gauntlet which even a plausible application would have to go through. Once the applicant assembles the very demanding corpus of financial and legal documents necessary to even begin an application for Economic Hardship, the applicant would still have to expect probing by expert consultants, a thorough public hearing, intervention by City Council, and more. Even once all this is complete, there’s simply no guarantee that a certificate would actually be granted.

For a building in as good repair as 142 Free Street is, and for an organization the size the PMA is, this option is simply off the table.

And… that’s all. There is no backdoor to the HP ordinance. “Contributing” structures cannot be demolished, and if 142 Free Street is “contributing,” then the PMA’s plans are dead in the water. A way forward is available if, and only if, 142 Free Street isn’t “contributing” after all. Since 2009, when the classification was first made, the building hasn’t undergone any sort of disfigurement or disaster, so the only plausible argument that the old Children’s Museum is “noncontributing” is to assert that it should never have been considered as contributing to the Congress Street Historic District in the first place.

The Congress Street Historic District

As previously mentioned, all Historic Districts have a “description” which details the history, visual character, and other features of the district. This description serves as the documentary basis for decisions made about the district, such as whether or not a new building would be appropriate for the district. The description for the Congress Street Historic District can be found here.

The full document is about eight pages long, but a passage around which much of the discussion has turned can be found on page six, underneath the heading “Visual Character,” and which has been presented below, with added emphases –

“The visual character of the district is rich and varied. Unlike several other historic districts in Portland, which were largely constructed within a limited ‘period of significance,’ the character of the Congress Street District is one of layered historical development over time. This results in an area with a delightful mix of historical architectural styles from 18th century Colonial and 19th century Federal to 20th century international and 21st century Post Modern styles, with examples of nearly every significant style of residential, commercial and civic architecture in between. This diversity of styles has been part of the area’s visual character since early in its history and (with a number of large underutilized lots within its boundaries) its continuation into the future is likely.

“Represented in the district are the works of many prominent architects from the early 19th through the 20th centuries. Maine architects and architectural firms that have contributed to the street include Charles Quincy Clapp, Francis H. Fassett, Frederick A. Thompson, John Calvin Stevens, George Burnham, John P. Thomas, Miller & Mayo and Orcutt Associates.”

Does 142 Free Street fit this description? Notably, the building’s architect John Calvin Stevens is listed explicitly by name, and the mix of styles and time periods could easily include the building’s late-19th/early-20th century Colonial Revival character. On the other hand, the building’s specific style is not named, so it can be argued as distinct. Likewise, John Calvin Stevens did design at least one other building in the CSHD’s boundaries – the L.D.M. Sweat Memorial Galleries, also owned by the PMA – and so it can be argued that the reference to Stevens means this design of his, and not 142 Free Street. But ultimately, whether or not 142 Free Street fits within the description, too, will be decided by the City Council on Monday.

How to Become Noncontributing

It was foreseeable that some properties which were classified as “contributing” may have been called such in error, or that changes in circumstances could nullify the contributions of a “contributing” site. Therefore, the Historic Preservation ordinance briefly outlines the process for how to go about amending the classification of a “contributing” property in section 17.5.9 of the Land Use Code.

The process is straightforward, if involved. At the request of either the property’s owners or the City Council, the petition to change the classification of a property goes first before the Historic Preservation Board, which reviews the facts and makes a recommendation to City Council. Then, the Planning Board holds a similar hearing, also reviewing the facts and making a recommendation to City Council. The City Council then holds a third and final hearing itself, taking into consideration the recommendations (while in no way being bound by them) and making a final judgment. The Historic Preservation and Planning Board hearings have already taken place, and their decisions will be briefly surveyed in the following segment.

–

The Historic Preservation Ordinance, In Summary

With these explanations in hand, the reader should have a firm footing to understand what the City Council will be voting on this Monday. To recap this survey of Portland’s HP ordinance, remember the following points:

- 142 Free Street, built in the 1830s originally, underwent a series of major design overhauls in its early life but was settled into its current form by 1958.

- Nevertheless, some moderate renovation did continue after this, including additions made in the 1990s.

- 142 Free Street is located in the Congress Street Historic District (CSHD), which was designated in 2009 and is intended to preserve the “delightful mix of historical architectural styles” from 1959 and earlier.

- 142 Free Street has been classified as a “contributing” structure in the CSHD since the original report, meaning that officials determined it helped form the historic fabric of the district.

- “Contributing” structures cannot be demolished.

- The one exception to this rule, Economic Hardship, is almost certainly not applicable to the PMA or 142 Free Street.

- The PMA is arguing that the building should never have been considered “contributing” in the first place.

- The City Council, and the City Council alone, has final judgement in determining whether or not they are correct.

Boards and Board Decisions

The reader will recall that the question at the heart of the matter has two halves –

First, was the decision to classify 142 Free Street as “contributing” to the Congress Street Historic District in 2009 made in error?

And, if not, should the Historic Preservation ordinance be amended?

The second half, whether the ordinance should be changed – a question of judgment and prudence – is something which can only be considered by the City Council, which is made up of elected officials. The first part of the question, on the other hand, does not ask what the law should be, but only what the law currently is, and how to apply it. For most questions of how to apply the law, the city relies on its staff and its boards of appointees, in this case the Planning Board and the Historic Preservation Board, on which this author serves.

Boards like the HP Board are constituted of unpaid citizen volunteers, interviewed and selected by a Council committee and appointed by a vote of the whole City Council. With the help of city staff who are charged with facilitating the work of the boards, these bodies of unelected representatives make decisions on how to apply the laws which the City Council has passed. Boards may also be asked to make recommendations to the City Council on various issues within their domains, and they can hold hearings to review projects and proposals which the Council couldn’t possibly have time for. In short, boards are charged with making the countless little decisions necessary to apply modern laws. They are not in the business of making up the law themselves.

Boards do not possess any independent authority, all of their decisions are ultimately subject to the judgment of the city’s sole legislative body: City Council. As we live in a democracy, it the elected representatives, and not any of their unelected bureaucrats, (myself included,) which have the last word.

So, per the directions of the HP ordinance, both the Historic Preservation Board and the Planning Board were asked for recommendations on how the ordinance applies to 142 Free Street. The question before both of these boards was not “Would the PMA’s expansion be a good idea?” Or “Is the Children’s Museum an important building?” Rather, according to the boards’ legal counsel, the task was simply to determine whether the standards of “contributing” or “noncontributing” best applied to 142 Free Street.

This was not, however, the focus of most of the commentary around the hearings. The PMA’s application packet, running a whopping 112 pages, addressed the question, but also spent a great deal of effort making a variety of arguments orthogonal to the primary question. Others followed suit, with public commenters, nonprofit groups, and journalists either condemning the PMA’s plans or condemning the law for standing in their way.

It was the unanimous position of the HP Board that 142 Free Street clearly met all the criteria for being a “contributing” structure. This does not mean that the members of this board were opposed to the PMA’s dreams, it simply meant that the law as on the books today did not permit any alternative interpretation. When I offered my thoughts from the dais, I tried to capture this position. “I feel that the PMA is asking us for something we don’t have the power to give,” I said. It wasn’t our job to change the law, only to read and apply it.

The Planning Board hearing followed a similar course. Though not unanimous, (member Marpheen Chann dissented on account of a disagreement with the legal interpretation of the Planning Board’s purview,) the consensus reached there echoed the HP Board’s. The standards for “contributing” structures, on a plain reading, applied to 142 Free Street. Representatives from the PMA were not particularly put out by either of these decisions, considering them as expected. They knew the real decision would be in the third hearing.

So both the HP and Planning Boards have sent their recommendations – that the HP ordinance as written classifies the building as “contributing” – to the City Council, for the third and final hearing before them. But the Council exists at a higher plane of consideration. The Council doesn’t just interpret the law, it makes the law.

The Open-Ended Question

The second half of the question being asked of the City Council on Monday is

And, if 142 Free Street is a “contributing” structure, should the Historic Preservation ordinance be amended?

The City Council has the opportunity to disagree with its subordinate boards and find the opposite conclusion, that 142 Free Street should never have been called “contributing” and should be re-classified. The PMA’s representatives have said they’ve always been aiming for this outcome, and aren’t arguing for any greater reform.

But the City Council also has the opportunity to agree with the HP and Planning Boards, also finding that the building is “contributing,” but deciding that the project should go ahead anyway.

Portland’s Historic Preservation ordinance is relatively strict. There are no avenues for owners of “contributing” property to take if they want to demolish their viable buildings, even to make way for universally-loved proposals. Should there be?

The danger of weakening the ordinance is obvious, it could undermine the entire point of the law – to preserve the city’s historic character. But should there be some sort of ‘out,’ some sort of release valve to allow good projects through anyway? Maybe you don’t consider the PMA’s new wing to be one of these “good projects,” but one could just as easily imagine a new hospital, affordable housing, transit infrastructure, or a public library being proposed instead. Should any of these projects have an exception?

There are infinite ways which the Council could amend the HP ordinance. A broad-based loosening of the law could kickstart a boom of activity in the city’s Historic Districts, or a very narrowly-tailored exception could feasibly never be applied to any other project again. We’ll just have to wait and see what the assembled councilors can come up with together.

Be sure to keep an eye on the City Council meeting this Monday, May 6th at 5:00 PM. If – now that you understand the question – you want to make your voice heard, be sure to offer your public comment or get in touch with your councilor. Historic Preservation is the protection of our heritage, not a blockade against progress.

Ashley D. Keenan – Ashley is an editor of the Portland Townsman, with work focusing on the mechanics of local government and housing policy, and also a member of Portland’s Historic Preservation Board. You can reach Ashley personally at ashley@donnellykeenan.com

Thank you for this great reporting!

That was a great lesson on what is being considered. Thanks a bunch, you all are providing a great civic service to Portland.

This is a laughably bad (and self-serving) analysis of the situation which pretends that the poorly drafted (intentionally so) legalisms that the historic preservation ordinance purports to stand on can remove the inherent subjectivity of the whole exercise of “contributing” classifications and the designation of historic districts in Portland. As per the practice of our historic preservation regime here in Portland, virtually no actual history informed anything in the decision-making process – not an honest appraisal of the original creation of the Congress Street Historic District (an embarrassing NIMBY exercise conceived to stop the energy seen during Congress Street’s (mostly the “Arts District” area) brief revival between the late 1990s and 2006 and locked down during the worst days of the Great Recession in early 2009 when most everyone was distracted) nor the anti-democratic nature of the entire historic preservation kludge which uses wide-open, subjectivity to bring properties into its regulatory talons but then insists afterwards that the same loose, substance-less standards cannot be re-evaluated with fresh eyes by public officials down the road.

The HP Board and the Planning Board were more than happy to engage in a lazy, superficial examination of the situation while the cowardly (and equally self-serving) city planning staff helped to muddy the whole saga with confusion, outright misinformation and avenues of review completely untrodden. They did not wrestle with anything, they merely punted after using city staff’s evasions as cover.

Also, the author should source material it borrows from other places. For example: https://www.mainememory.net/record/25661

The PMA has made available a host of material regarding this situation and of course Greater Portland Landmarks has done so as well. Links below:

https://static1.squarespace.com/static/594bea6eccf210316877b8f2/t/6500a8789bd27118fe98f9c0/1694541949808/History+of+142+Free+Street.pdf

https://static1.squarespace.com/static/594bea6eccf210316877b8f2/t/6500a7f518e09a5b6283862e/1694541813515/Application+Letter.pdf

https://www.portlandmuseum.org/aspects-of-integrity

[Links came from here: https://www.portlandmuseum.org/blueprint%5D

Here is a link to the Greater Portland Landmarks jihad page on the matter: https://www.portlandlandmarks.org/pma-key-talking-points [at the end of this page is a link to their more comprehensive microsite on this issue]