This article has been adapted and updated from prior work published on The Portland Townsman. As disclosure, Ashley Keenan lives in an apartment covered by the current rent control ordinance.

This article is the first in a three-part series on 2023’s Question A.

Portland’s voters have seen referenda on rent control presented before them in November 2020, November 2022, and June 2023; now Portland once more is facing a citizen’s initiative to modify the city’s rent control ordinance.

Before being able to make an informed vote on these proposed changes, however, one must possess a firm grasp on how the ordinance works today. Since St. Paul, Minnesota weakened its own stabilization ordinance, Portland’s recent foray into municipal-level rent control is unique on the national stage. Indeed, when considering only those still-current laws affecting new construction, Portland has a persuasive claim to have the strongest local rent control laws in the United States. (New York City’s patchwork of legacy laws, such as those which continue to hold down certain 3-bedroom apartments on the Upper East Side to $1,300/month, remains the king without said consideration.)

For this reason, there are eyes on our ordinance not just from Portland, not just from Maine, but from left-wing activists and wary landlords around the country. Will our policy stand? And if it does, will it succeed?

So, what is this law which has placed our city near the center of the national rent control debate?

Who’s Covered?

Portland’s rent control ordinance (Chapter 6, Article XII) was implemented by referendum in November 2020, and amended by referendum in November 2022 to strengthen its provisions and address loopholes in the original ordinance. In both referenda, the sponsor was the Maine chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). Many features of the law which has been so handily approved by Portland’s voters are unique to it, and so no standard reference can be made for understanding it. We have to go provision-by-provision in the Portland Code of Ordinances.

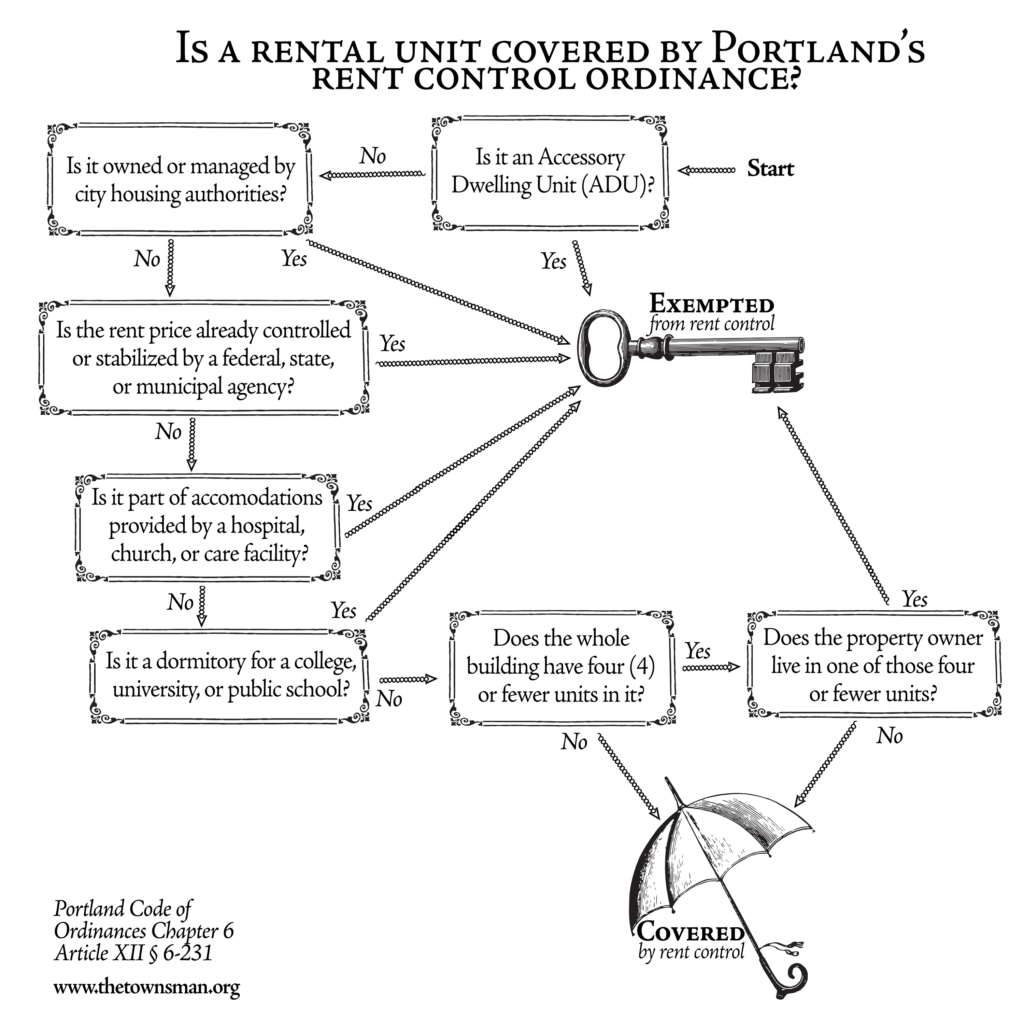

The first thing to understand is which rental units are “covered” by the policy – that is, have their rent prices controlled by the ordinance’s provisions – and which units are exempt.

City-owned, city-managed, hospital, church, care, or dormitory units are generally exempt. As are Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), and those units whose prices are already stabilized by a federal, state, or local agency. Further, if the whole building has four or fewer units, and the owner of the building lives in one of those units, then those units too are exempt. The rent prices of exempt housing units are entirely unaffected by our rent control ordinance, so we can just put them out of our minds. Generally speaking, all other housing units rented to tenants are “covered.”

Jargon and Limits

If a unit is “covered” by rent control, it will have two relevant characteristics that are important to understand: its Base Rent and its Current Rent. All covered units have both.

• If a unit was on the market on June 1st, 2020, the Base Rent is what the unit’s rent price was on June 1st, 2020.

• If a unit wasn’t yet on the market on June 1st, 2020, the Base Rent is the rent price the unit was first rented for.

• The Current Rent is simply whatever price it is currently being rented for.

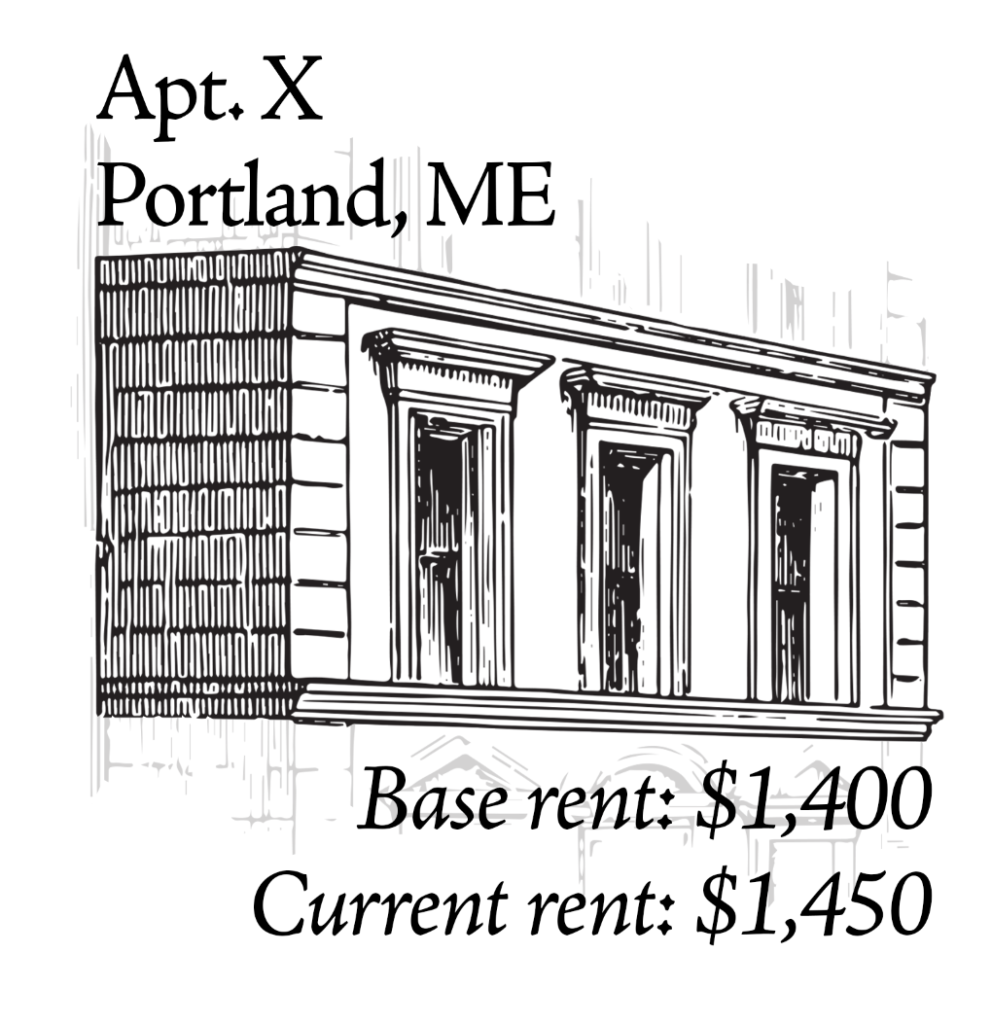

Let’s imagine a covered unit, “Apartment X,” which rented for $1,400 per month on June 1st 2020, and was renting for $1,450 in 2023. We’ll use this apartment as our baseline.

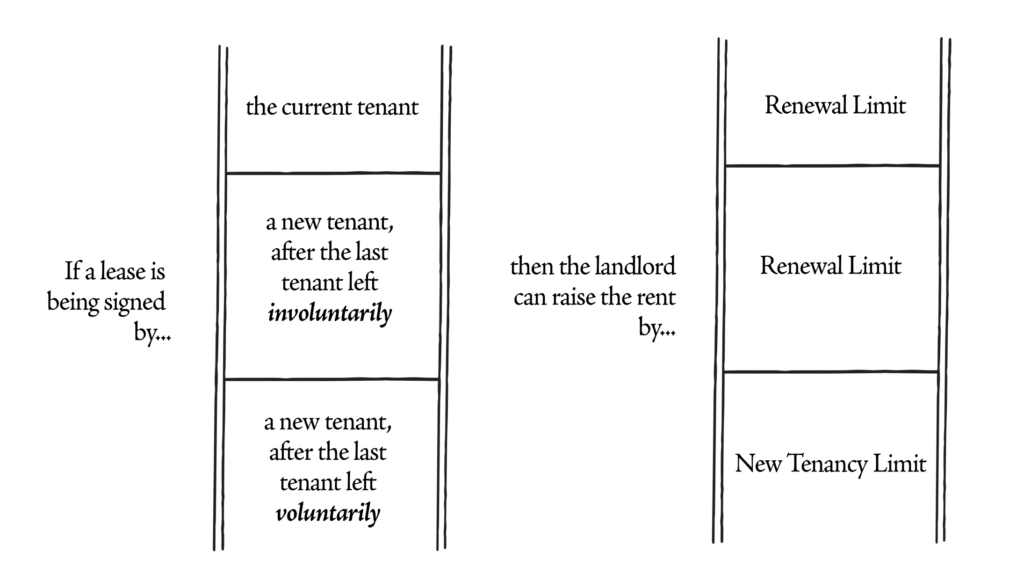

Landlords are allowed to increase the rent price on their units once per year, at most, and this increase is numerically limited. How much it’s limited depends on the scenario:

As you can see, there are two different limits, a Renewal Limit and a New Tenancy Limit. (N.B. These are colloquial, rather than legal, terms.) The first thing to note is that in all cases, whether a lease is being renewed by a current tenant or is vacant and being leased by a new tenant, landlords are restricted in how much they can raise rent. In policy terms this is called “vacancy control,” and can be contrasted against the more common “vacancy decontrol,” which allows landlords to freely set rents to market rate when the unit becomes vacant.

The Renewal Limit, the increase which can be charged to tenants renewing their lease terms, is lower than the New Tenancy Limit, the increase which can be charged to new tenants moving in following a vacancy.

Importantly, however, Portland’s ordinance also does not treat all vacancies equally. If a landlord declines to renew a lease with a tenant, or if a landlord evicts a tenant, the vacancy that follows is considered an “involuntary vacancy.” Involuntary vacancies, as a disincentive for landlords to harry out tenants, hold down rent increases to the Renewal Limit. Without this measure, a landlords could profit more by replacing a tenant than by renewing with them.

On the other hand, if a tenant voluntarily leaves a lease early, or if they are offered to renew the lease but choose not to, the vacancy which follows is a “voluntary vacancy.” In this case, landlords have the opportunity to raise rents by a slightly higher limit, as it will not potentially displace the current tenant.

Calculating the Two Limits

The following examples are for illustrative purposes only, they do not constitute actual estimates of permissible rent increases in Portland for this year or any year.

The Renewal Limit, based on the “Allowable Increase Percentage,” is calculated each year by the Housing Safety Office using the inflation rate (CPI) as measured by the United States Bureau of Labor for the Greater Boston Metropolitan Area. Specifically, the limit shall be set to 70% of the inflation rate for the preceding year, applied to the Current Rent of the unit.

As an example for illustrating the manner in which the Renewal Limit is calculated, let’s use the national CPI inflation rate from 2021 to 2022: 8%.

And now let’s go back to our example apartment, which has a Base Rent (its price in June 2020) of $1,400, and a Current Rent of $1,450.

First, we apply the limit rate (70%) to the inflation rate: 70% of 8% is 5.6%

Then we apply this new rate to the Current Rent: 5.6% of $1,450 is $81.20

Finally, we add this dollar figure to the Current Rent: $1,450 + $81.20 = $1,531.20

If you’ve managed to follow this, we can see that the maximum rent a landlord could now ask of their tenant, assuming that they receiving the Renewal Limit, is $1,531.20.

The good people at City Hall don’t actually expect everyone to do this math themselves (they’re not the IRS) so they provide guidelines each year for landlords to comply with. It is worth noting, however, that this binds landlords to raise rents at a lower rate than inflation. This means that every year they are bound by the Renewal Limit, assuming they’re not entitled to other increases, their unit provides less real revenue than the year before. It is this provision, which amounts to a real decrease in the price of rent each year for renewing tenants, that makes Portland’s ordinance stand out among municipalities with rent control laws.

When a unit has become vacant from the tenant(s) leaving voluntarily, however, the landlord can raise the rent by the New Tenancy Limit, which is the Renewal Limit plus an extra 5% of the Base Rent. For example:

First you calculate the Renewal Limit figure: As calculated above, $81.20

Second, you calculate 5% of the Base Rent: 5% of $1,400 is $70

Then we add these two together: $81.20 + $70 = $151.20

Finally, we apply this dollar figure to the Current Rent: $1,450 + $151.20 = $1,601.20

So, the new total rent, for a new tenant following a voluntary vacancy, could be as high as $1,601.20, right?

Absolute Maximum Limit

No. There is an absolute maximum limit to annual rent increases set at 10% of Current Rent per year. This means that no matter what additional increases a landlord may be entitled to on top of the Renewal Limit, our $1,450 rent price is absolutely limited to a one year-increase of $145. So, the new rent can be $1,595 or less.

This is the total rent, $1,595, that a landlord could ask of a new tenant, assuming the previous tenant left voluntarily. A common question to arise is “How do we know that a tenant’s departure was actually voluntary?” The rent control ordinance charges the Housing Safety Office (HSO) with the responsibility to investigate any report it receives that a “voluntary” departure was in fact coerced. The HSO earlier in 2023 added several new hires to its staff, partially with the intention of making enforcement of this policy more reliable.

This Absolute Maximum Limit of 10% per year is important to understand. The drafters of this past June’s referendum didn’t understand it, and handicapped their own proposal in doing so. (cf. “Does it Override the Cap?“)

It also means that extra $6.20 can’t be added to the rent.

Banking Raises

But where did that extra $6.20 “go”? When a landlord’s theoretical limit exceeds the absolute 10% maximum, any additional percentage increases are ‘banked.’

There are all sorts of reasons why a landlord might not want to max out their annual increase limit. Maybe they know their tenant is going through a hard time, or maybe they’d rather just use “$1,530” instead of “1,531.20” on their invoices. And of course, as we have seen, sometimes landlords are obligated to bank some of their allowed raise in order to comply the absolute maximum limit. Whatever the reason, whenever a landlord does not ‘max out’ their limit, they ‘bank’ whatever increase they chose to forgo.

This banked increase can then be applied by the landlord in a later year. This is intended to provide some flexibility for landlords, and to incentivize them to not necessarily max out their rent raises each year. The sum of the Base Rent plus all actual and banked increases is called the Banked Rent, and represents a theoretical maximum rent price.

Banked increases cannot be used to exceed the absolute maximum limit of 10% for annual rent rises. It’s the absolute maximum. With this in mind, a common complaint of Portland’s rent control scheme is that in medium-to-high inflation economies (like the one the United States is only now beginning to exit) it is possible that landlords will accumulate large ‘banks’ of increases that they can never actually ‘spend,’ as they are already hitting the 10% maximum. But even if a landlord hasn’t stored up banked increases, there are other ways to obtain allowed increases.

Additional Raises and the Rent Board

An interesting piece of jargon in the rent control ordinance is “fair return on investment.” This is defined in the code as the amount of profit sufficient to allow a “just and reasonable rate of return, to encourage the investment of capital in the rental housing market, to fairly compensate investors for the risks they have assumed, and to achieve minimum constitutionally protected standards.” It goes on further to state that, in typical cases at least, the amount of profit earned by landlords for the 2019 fiscal year should be used as the baseline for a fair return on investment. A system for evaluating the profitability of rental units was introduced by St. Paul in Minnesota based on the principle of “Maintenance of Net Operating Income” (MNOI), a long-standing legal precedent in determining a fair return under rent control ordinances. With this framework, they ask for a substantial amount of data from landlords requesting additional raises, and calculate what to offer them. In 2022, Question C included implementing similar guidelines here in Portland.

On March 20th of this year, rules complying with the MNOI-based ordinance were approved for the Rent Board. Multiple members of the City Council criticized the rules as being too complicated for small-time landlords, requiring full-time accountants and attorneys, but the chair of the Rent Board conveyed that his hands were tied. He agreed that the forms his team produced were very complicated, especially for “smaller” landlords, but that the referendum-enacted statute did not allow for any simplifications to be made.

The attitudes of these “smaller” landlords are at the heart of the November 2023 referendum.

This Rent Board was also established by the referendum of 2020, and its primary concern is to arbitrate this issue. Landlords who wish to raise rents higher than the limits prescribed in the law have to make their case to this board for why they are justified in doing so. The board is composed of seven members, appointed by the mayor and confirmed by the City Council. While not mandatory, the ordinance suggests that they include at least three tenants and no more than three landlords. The Board has suffered from extended periods of vacant seats over the past three years, and even today the District 3 seat remains vacant for want of volunteers.

If the Rent Board sees fit to allow for additional increases, then they can authorize the landlord to do so. Not even the Rent Board, however, can exceed the absolute maximum limit of 10% per year. It’s the absolute maximum.

The Rent Board may also consider adjusting a unit’s Base Rent, a very difficult thing to change under the current ordinance, but only following a “major renovation or reconfiguration” as described in §6-233(c). The only other way for a single unit’s Base Rent to be reset is by taking it off the market for more than five years before leasing it again. Should a landlord ever deem a unit to be unprofitable, they have the option of removing its tenant at the end of their lease and holding the unit off-market for five years, at which time it can re-enter at market price.

Even with this system in place, and with a competent Rent Board at hand, the idea of a “Fair Return on Investment” still inevitably remains subject to differences of opinion. This is especially the case for the question of “encouraging investment,” which will always be a relative comparison to other towns. For an ordinance drafted by avowed socialists and intended to apply to landlords, a capitalist class if there ever was one, we can reasonably assume there will be quite distinct conceptions of what a “fair return” really is.

Other Provisions

The rent control ordinance, beyond this core mechanism for holding down the rent prices of covered units, also implements a number of satellite regulations for landlords to adhere to.

One of these is a popular ban on application fees, which bans both discretionary processing fees as well as expense fees for running background or credit checks. Applying for an apartment must always be free of charge in Portland. While the usual economists correctly point out that the expenses for such work are inevitably rolled into the rent price instead, advocates nevertheless champion this removal of a perverse incentive to receive as many applications as possible – holding the unit vacant in the meantime – before finally entering into a lease.

Another popular element is the extended notification periods prior to the termination of tenancies, boasted of by tenants’ advocates for offering security and dignity to tenants while costing landlords little to nothing in money. The termination of any long-term tenancy must be preceded by a 90-days’ notice from the landlord to the tenant, in order to give the tenant enough time to make other arrangements. (Short-term rentals, naturally, are exempt.) This definition of a termination includes the intention to not offer a renewal to the tenant at the end of a lease term.

The landlord can shorten this period by paying up, however. By refunding one month’s rent payment to the tenant, the landlord can legally provide a 60-day notice instead. With a two months’ refund, the landlord can get away with just 30 days. If you open your mail to discover you have 30 days to get out, at least you should receive a sizable check in the same envelope.

The tenant protections also include strong anti-discrimination rules, some of which are redundant by state- and federal-level protections. Nevertheless, written out in the city’s code can be found – on top of the usual bans on discrimination based on race, sex, disability, nationality, sexuality, etc. (curiously not religion) – landlords shall also not refuse as tenants any recipients of government assistance, nor shall they judge any source of income to be different from another, nor shall they retaliate against any tenant for organizing a Tenants’ Union.

These provisions and others can be read in full in Chapter 6 of the city’s code, notably in Articles XI, XII, and XIII.

Knowing Where You Are

Before one can understand the November 2023 referendum, Question A, one must understand the law its modifying. Careful readers, if I’ve done my job, should now be able to confidently say that they do. Once we know where we are, we can look at where we want to go.

Learn more about the proposed changes in Question A in Part 2, coming soon.

Ashley D. Keenan – Ashley is an editor of The Portland Townsman, writer, local small business-owner, and Maine native. Her work primarily covers the mechanics of local government, the ongoing housing crisis, responsible market economics, and New England culture and history. She lives in Portland with her fiancé and can be personally reached at ashley@donnellykeenan.com.