According to the U.S. Census, Maine’s population grew by about 44,000 souls from 2010 to 2021. Being from a small, rural, sleepy state tucked into one of the most overlooked corners of the union, many Mainers regard this figure with no small measure of anxiety – if not fear. Nearly all of our local- and state-level political discussions eventually invoke population growth as some confounding factor.

But despite seeming such an incessantly-summoned statistic, there are many ill-informed assumptions and mischaracterizations beleaguering the conversation. So, as the title asks, who exactly is coming to Maine? Where are they coming from? And why are they coming here?

Well, first, not everyone is coming here from somewhere else. Some of the population growth is ‘organic’, local families having children. But for those who have come to our state from somewhere else, this can be further divided into three broad categories: those who move to Maine from other states, those who move here from abroad, and refugees and asylum seekers coming from places ravaged by war and other afflictions. After reviewing some general data about population growth, we’ll approach each of these categories in turn. While discussing domestic migration, we’ll also review information regarding intra-state migration, between the Greater Portland area and the rest of Maine, a sub-topic which also bedevils this conversation.

Before continuing, please note that this article primarily serves to provide factual information and context for this information, not advocate for any particular policy platform. Nevertheless, in any document wordier than an Excel spreadsheet, bias is bound to creep in, mea culpa.

General Data

First, please note that almost all population statistics are inexact. I will avoid overly specific figures, in general, to avoid the illusion of certainty in exact numbers. Tracking hundreds of millions of people will inevitably incur substantial margins of error, all the more so as Maine is such a sparsely populated state. Bear this in mind.

The past three years have been an exceedingly abnormal period for statistical analysis in all fields. The COVID-19 pandemic, with its associated crises, has made it so that observations drawn from data even a couple of years old can be woefully inaccurate. Can, for example, trends from 2010-2019 be meaningfully applied to 2020-2022? Maybe, but maybe not, depends on the trend, and it won’t be until years from now that we can confidently sort out what the long-term effects of these disruptions are. This intrinsic weakness will be a running theme throughout the figures presented, so just keep that in your back pocket too.

The most obvious way in which the abnormality of these past years is felt in just how radical the increase in population was from 2019-2021, as opposed to 2010-2019. According to numbers from the Office of the State Economist, from 2010 to 2019 – a decade – Maine’s population increased by approximately 15,800. In just the two years that followed, from 2019 to 2021, Maine’s population increased by approximately 28,200.

Inaccurate estimates in the years leading up to Census 2020 could render the sudden jump slightly less stark, if found, but the general impression that Maine’s population has rapidly increased over the past two years is certain.

One point of data not affected by the pandemic is one that many find unintuitive, fewer and fewer people move every year. Despite much talk of rootlessness and displacement, the U.S. Census provides some evidence to the contrary. Both the absolute number and per capita rate in the United States of people moving from one residence to another has been steadily decreasing since the early ’80s, and the trend has continued through 2021. Only 8.3% of Americans moved last year, while over 20% did in 1985. Of those that did move in 2021, more than 60% stayed in the same county as they moved from, while fewer than 20% moved to a different state.

What does this mean? Well, on its own, not much. But it may act as a counterweight to the notion that housing instability is manifesting primarily as apartment-hopping and inter-city migration. Indeed, this fact may indicate that when faced with rising housing costs, people are more likely to stay put, even in less-than-ideal circumstances, out of fear of being unable to find suitable housing elsewhere. But this is conjecture.

How do Maine’s numbers compare to the rest of the country? As stated earlier, Maine’s population grew by about 44,000 people, or about 3.3%, from 2010-2021. During the same period, as a whole, the United States’ population grew by 7.5%, over twenty million new people. Compared to the rest of the U.S.A., Maine remains a small state with a relatively low rate of growth. It’s important to keep this in mind. The challenges facing Maine are real, but they’re nothing that the rest of the country isn’t experiencing too, and we are certainly able to overcome them.

Organic Growth

While most of the conversation about population growth is tied up with questions about migration, organic growth shouldn’t be forgotten. That said, there’s a pretty good reason it’s often left out. According to the CDC, the 2020 birth rate in Maine is 49.2 per 1,000. This puts us sixth from the bottom across all states. There are not a lot of children being born in Maine, and it’s trending downwards, falling from a still-low rate of 53.4 per 1,000 in 2015.

This has resulted in a fairly consistent number of live births every year, hovering around 12,000 (again, trending slowly downwards.) During the period from 2010 to 2021, approximately 136,700 people were born in Maine, and approximately 170,600 people died.

With these figures in mind, we can see Maine’s net organic growth is actually an organic decline of about 34,000 people. I think it’s worth dwelling on this grim result. We take it for granted that Maine is a state with many senior citizens, but that so few Mainers are starting families, and that so many young Mainers leave for other states, should really make us think about the policy decisions that may contribute to this de facto antipathy towards youth and families. What will the future hold? How might we make a state which welcomes families, which gives a stable foundation for those who wish to have children, and which is appealing for young locals to stick around in? I have no pithy answer to end this paragraph with, it’s a difficult problem.

But during the same period, Maine’s population grew by approximately 44,000 people. So how is this discrepancy of roughly 70,000 people made up for? Naturally, by migration, both foreign and domestic.

Domestic Migration

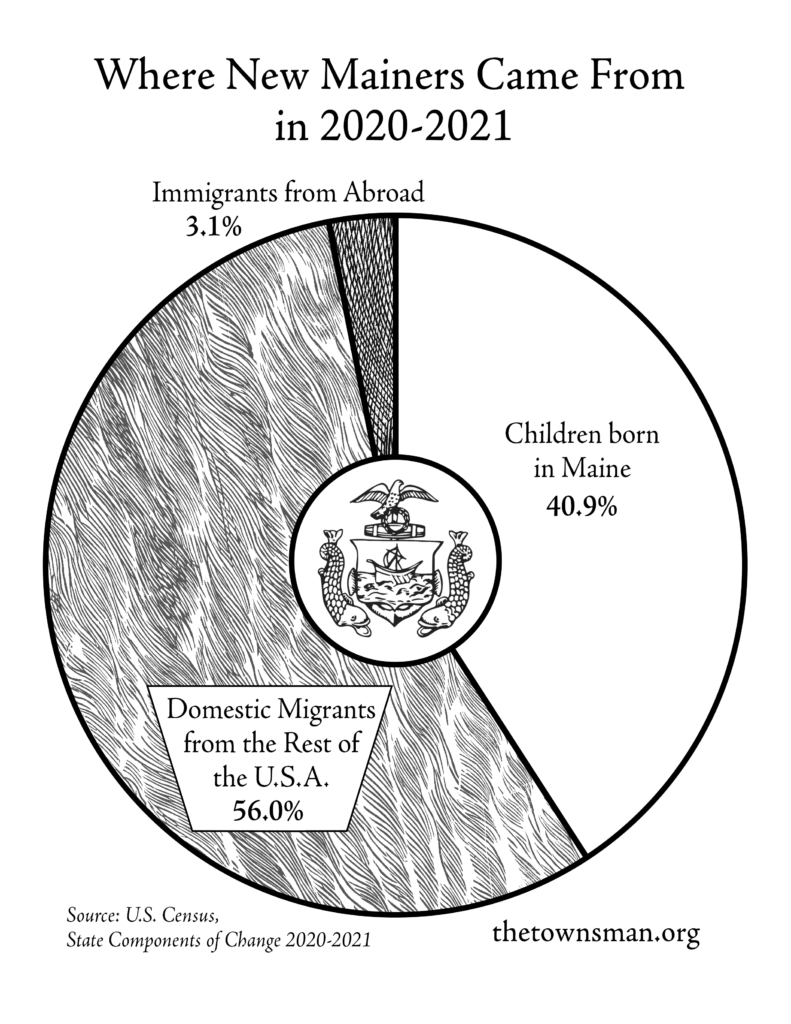

Domestic migration makes up the largest share of population growth, by far. From the Census, despite the organic decline of over 6,000 people from 2020-2021, we more than made up for that loss with an inflow of Americans from other states to the tune of roughly 15,500 people. Of the new Mainers in 2021, 40.9% were children born here, and 56% were domestic migrants from other states. The remaining 3.1% were immigrants from abroad. This general ratio seems to be characteristic of the last several years, and will likely continue to trend true in the future.

Where exactly are they coming from? Data, unfortunately, remains patchy for the 2020-2022 surge in population, but much more robust data can be had for the years up to 2020. From trends collected by the U.S. Census, the rest of the New England states, especially New Hampshire, naturally make up a substantial portion of the inflow. To a lesser extent the same is true of other high-population northeast-ish states, especially New York and Pennsylvania, and further to the south, bustling North Carolina. California sends a thousand or two of her residents to us each year, but for such a large state, this isn’t disproportionate. The only state which really punches above its weight is Florida; in some years Florida has even beat New Hampshire in migrants to Maine. This transfer of populations can be largely chalked up to the retirees and other persons that travel seasonally between the two ends of America’s Atlantic seaboard, but with Florida becoming a more dynamic economic destination for other kinds of migrants, it should not be thought of as only a retirement destination.

All of these states with high inflow to Maine are also the destinations for significant outflow from it, mostly proportionally. One odd artifact in 2019 showed a minor exodus of Mainers to Kentucky, with nearly 2,000 people seemingly moving there from Maine, this over the less than 200 who had moved there in 2018 – but the Census also marked this figure with an unusually large margin of error. It’s likely this is just an inaccurate estimate and there was no Great Kentucky Migration, (interesting of a story as this would be.)

State-level data, while useful, can smear more interesting and granular trends. Although since nearly all of Maine’s population growth happens in Greater Portland, (the rural north has, sadly, been in decline for a long time), in most respects, what’s true of Maine is true of Greater Portland. But while getting granular on the receiving end doesn’t reveal much new information, we can delve deeper into the metropolitan areas across that new Mainers are hailing from.

Inter-city migrants make up a substantial portion of those moving between states, typically following career advancements or seeking cost-of-living relief. The U.S. Census Bureau tracks these citizens that move from city to city, and the collected data from 2015-2019 is an interesting glimpse into the cities Mainers move to and from.

By far the greatest single source of out-of-state domestic migrants to the Portland-South Portland Metro Area is Boston. It’s not even close. More than 4,000 people moved to Portland from Boston from 2015 to 2019 – however, nearly as many moved in the opposite direction. Approximately 3,600 Portlanders moved to Boston. The outcome is a modest net-migration figure, (about 600), but this obscures the substantial mutual population flows that bind Portland and Boston together. Students, graduates, and young professionals seek out higher-paying work and city life in Boston, while the Hub’s older professionals, new families, and seniors are attracted to Greater Portland.

Even including intra-state migrants, Boston is still the most notable urban partner to Portland. But the rest of Maine does constitute the other major source of domestic migrants into Portland, with over a thousand people from Bangor, and over 1,500 people from Lewiston-Auburn moving in. But again, these strong numbers bring with them counterflows, and in fact, for both Bangor and Lewiston-Auburn, there were more people moving there from Portland than people moving to Portland from there.

No other metro area in the United States compares to Boston and other Maine cities in terms of absolute numbers.

What can we conclude from this data? Most notably, that our special relationship with Boston results in a great many migrants in both directions, and this exchange of humanity is surprisingly balanced. Meanwhile, there is much in Maine’s smaller cities that is apparently drawing Greater Portland’s residents to them. Besides these two relationships, with Boston and with the rest of Maine, there aren’t any particularly strong affinities that Portland has with any other metro in the country, only weak trends towards NYC, Floridian cities, and southern California. Note, however, that Portland is not a popular destination at all for west coasters, despite occasionally hearing that we’re being swamped by Californians.

This dataset concludes prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which doubtlessly will substantially change these figures, but any shift will likely be a short-term disruption, rather than a long-term adjustment in what cities Portland is organically paired with. This being said, preliminary post-pandemic data does suggest Florida is increasing in importance as a destination for Maine’s emigrants.

A Common Question: Is Portland’s population really the same as it was a century ago?

This canard often pops up, especially in discussions related to housing. It is typically deployed as an argument against the need for Portland to adapt to circumstances, as, since there aren’t more people in Portland, change is unnecessary. The following statement is, technically, correct: “Portland, Maine’s population is roughly the same today as it was in 1920.”

Wow! Right? Well, this lacks some serious context. First of all, Portland experienced serious population decline between 1950 and 1980, losing over 20% of its population during that period. The causes for this were manifold, ranging from mass demolitions of the city’s housing stock, to the collapse of local industries, to a nationwide trend of suburbanization, but its important to understand that this reversal of trends towards a growing population really only dates back to 1990.

But here’s why the statement is really misleading: during that same period, the Portland metropolitan area, including surrounding towns, has exploded in population, nearly quintupling from just over 100,000 in 1910 to now over 500,000. Why has Portland’s population stagnated while the suburbs see such enormous growth? There are, again, manifold reasons, but a large contributor is that Portland’s housing stock stagnated under restrictive anti-housing policies, while out in the suburbs new housing could sprawl outwards. This has resulted in a significant price differential, housing outside Portland is notably cheaper, but requires a longer commute if you work in the city. Would everyone who currently lives in the suburbs live in the city if there was less of a cost delta? Certainly not, but many, many would at least consider it. People like to live close to their jobs, and to other people.

For this reason, it must be understood that Portland’s seemingly stable population is a policy decision, not a natural invariable. The externalities of this policy decision should be considered carefully.

Immigration from Abroad

As earlier shown, only a single-digit percentage of Maine’s population growth comes from beyond America’s borders. In the explosive census period from 2020 to 2021, just 867 of the more than 16,000 migrants were estimated to be from abroad. But this area of growth hefts disproportionately in the minds of many locals, for whom it is the most visible sign of change. And there is good reason for this visibility!

The U.S.-born population of Maine increased by 3.9% from 1990 to 2000, and by 4.3% from 2000-2019. By comparison, the foreign-born population of Maine increased by 1.1% from 1990 to 2000, but by 42.8% from 2000-2019. And this is before the bulk of the asylum seeker influx over the past two years. This significant increase in the proportion of foreign-born Mainers over the past twenty years doubtlessly colors the perceptions of Maine’s growing population, especially in the eyes of our older residents who have seen this transformation happen.

This increase is somewhat exaggerated when using percentage figures, however, as Maine had a relatively small foreign-born population in decades past. In real figures, the image is a little less stark. From 2000 to 2019, the population of foreign-born Mainers grew from 36,691 to 52,419, an increase of 15,728 people, almost entirely concentrated in and around Portland. Of these folks, most are naturalized citizens, with fewer than 5,000 being noncitizens. This number has certainly increased with the crisis of refugees and asylum seekers, but non-citizens nevertheless make up a rather minute proportion of Maine’s residents. Further, approximately 14,480 of native Mainers as of 2019 had at least one foreign parent, indicating that most of the immigrants who have settled in Maine are putting down roots. According to Catholic Charities, (a key organization in handling immigration), Maine is a popular ‘secondary’ destination for people coming from abroad, both as asylum seekers and as economic migrants. This means that while initially arriving and living in some other state, migrants then make a second move from there to Maine. With this in mind, it’s no surprise that those who arrive here are content to make Maine their home for good.

Where are they coming from? Good question. Again referring to the data from 2019, about 22% of foreign-born Mainers are European in origin, about 28% Asian, 17.7% African, 11.2% Latin American, and nearly 20% Canadian. A small remaining portion hails from Oceania and other islands. More specifically, besides Canadians, a notable proportion of Maine’s immigrant population are British, Filipino, and East African.

Much of this data, however, is already showing its age. Over the past two years, Portland, like many other cities around the country, has been wracked with a new crisis, attempting to receive and care for an influx of refugees and asylum seekers.

Refugees and Asylum Seekers

This subject must be approached with care. No one can doubt the horrors of war and strife worldwide that drive good, decent people to leave their homes and seek safe passage and refuge in the arms of the United States – but many have doubts as to whether Maine has the capacity to adequately receive our share of this influx without pushing our resources to breaking point. What is our ‘capacity’? If we are indeed pushing against our limit, is this ‘limit’ on capacity intrinsic, or a matter of policy? To what extent must we prioritize the needs of entrenched locals against those of New Mainers? Must these interests be in conflict at all?

These questions vex Mainers, and often envenom discussions of policy. These questions entangle facts, statistics, assumptions, projections, ethical judgments, and moral intuitions in an often-unstable political alchemy. I will not be further discussing them here. I will try instead to disinterestedly present useful information about the ongoing crisis.

A brief refresher on definitions, a refugee is someone who has come to the United States already recognized by the government as someone fleeing war, violence, or persecution. Such individuals typically spend time in humanitarian camps or similar circumstances abroad, already having been displaced from their home, and while there, the United States recognizes their status as a refugee and gives them permission to enter the country. An asylum seeker is someone who fits, or believes themselves to fit, the definition of a refugee, but didn’t wait to come to the U.S.A. Instead, they entered America by some means, often under great duress, and now seek recognition and permission to stay permanently. If this recognition and permission is given, they are considered an asylee, roughly equivalent in legal terms to a refugee. Asylee status can take years to obtain, so until such status is granted or denied, they remain an asylum seeker.

It must be understood that adequate data on this matter is difficult to acquire. The best way to make estimates as to the size and nature of our asylum-seeking population is to look at figures relating to aid being distributed by Portland and Maine, especially housing aid. This, however, is problematic for two major reasons. First, there is certainly a number of asylum seekers who are not receiving aid out of a lack of need, a lack of trust, or a lack of knowledge. These individuals and families may be trying to sustain themselves, or they may be receiving aid indirectly through friends and relations, (bunking with them in city-provided housing, for example.) Such people usually make themselves known to ‘the system’ eventually, but this also requires transparency and clear lines of communication between the city governments, the state government, and the non-profit organizations which facilitate much of the on-the-ground business.

The second reason that relying on aid figures can be problematic is that it’s almost inherently invoking a policy discussion. Many on both sides of the argument find Portland’s and Maine’s response to this crisis wrongheaded, either for not doing nearly enough for these most vulnerable of people, or alternatively, for spending ludicrous amounts of money in unsustainable schemes. When talking about aid figures, it’s hard to avoid feeding into one of these polemical narratives. Still, they’re the best snapshot we have into the crisis.

As of July, Portland is housing about 1,450 Asylum Seekers, mostly in twelve local hotels. Portland spends about $1,000,000 on housing these asylum seekers and other unhoused persons each month, most of which is reimbursed with state and federal funds. But more than 35 families and 120 individuals seeking asylum don’t have any permanent shelter at all. These numbers were presented by the Immigrant Legal Advocacy Project after Portland announced, on May 5th, that the city can no longer guarantee shelter or services for new arrivals. The ILAP, with 79 other organizations as cosigners, urges that this guarantee be renewed, and asks other municipalities to assist.

This crisis is not totally unprecedented, in 2019 a sudden influx led to the city transforming the Expo into an emergency shelter. Even that famous surge, however, pales in comparison to the current challenge; fewer than 450 individuals had arrived in 2019. A stark difference, however, was that in 2019 the arrival of these people in need happened all at once, rapidly testing the city’s resources. Meanwhile the current crisis is a slower burn, with individuals and groups trickling into Maine over a much longer period. This can ease bureaucratic strain, but can also muddle planning.

How does this recent inflow of over 1,500 asylum seekers fit into the data we explored previously? In short, not cleanly. They make up about 15% of recent migrants, but categorizing them is difficult. Some are counted as immigrants from abroad, but as you may remember, in the period from July to July, 2020-2021, only 867 individuals were estimated to have moved to Maine from other countries. Wouldn’t that now seem to be an underestimate?

Not when you consider that many of these asylum seekers have arrived in Maine as a secondary destination, having previously sought refuge in another city immediately after arriving in the U.S.A., as Catholic Charities describes. With this in mind, many of these individuals and families would actually be correctly considered as domestic migrants. This can be unintuitive, but no source considers citizenship as a prerequisite to be counted as a domestic migrant.

And further, one must consider that many asylum seekers are not “on the radar,” avoiding tabulation for fear of state retribution. And some asylum seekers have had children while in Maine, so those infants would be counted as part of the organic growth and decline of the state. This means that when thinking about the previous categories, (organic growth, domestic migrants, and immigrants from abroad), an asylum seeker could reasonably fall into any of them, or none at all.

This is all to say that data in these cases is very incomplete, and even misleading. It’s a difficult enough series of problems as it is, but politicians trying to sink their teeth into it will be further frustrated by a lack of good statistics to use.

Conclusion

So, what to make of all this information? Well you don’t necessarily need to make anything of it. This said, there are a few large takeaways that I think are key for an informed Portland citizen to know:

1) Maine’s population has increased over the past decade by about 44,000 people, almost entirely concentrated in Greater Portland.

2) The bulk of this growth was during the period from 2019-2021, in which the population surged at unprecedented levels.

3) While this surge will likely represent local peak in the data, it’s likely that Maine will continue to see elevated levels of population growth compared to previous decades.

4) Maine’s ‘organic growth’, (in-state births, minus deaths), is deeply in the negative. Growth in population comes from migration into the state.

5) The vast majority of this migration is domestic, people coming to Maine from other states.

6) Portland’s strongest bonds are with Boston and the other Maine cities, exchanging with each thousands of people in both directions every year.

7) Strong inflow/outflow relationships also exist between Maine and the rest of New England and Florida, as well as, to a lesser extent, with New York, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina. California is notable as a destination for outgoing Mainers, but Maine is not a popular destination for outgoing Californians.

8) Immigrants from other countries make up a small proportion, about 3%, of Maine’s yearly growth.

9) Portland’s current refugee crisis does not cleanly map onto the rest of this data, with asylum seekers being difficult to count, classify, and consider.

10) Despite this statistical difficulty, a safe assumption is that approximately 15% of the recent population surge are asylum seekers and related individuals.

Growth is good. All living things must grow, change, and adapt. An organism which does not do these things is, in jargon terms, dead. And yes, cities are organisms, make no mistake. But growth presents challenges, and we must intelligently respond to them, with informed understanding, clear-sighted rationality, and not least, heart.

~

Non- or Partially-Linked Sources Consulted, (non-exhaustive):

Various reports, including Maine, State-to-State Migration Flows, Metro-to-metro Migration Flows, and others, The U.S. Census Bureau

Office of the State Economist, Maine

Division of Public Health Systems, Maine

Maine, Migration Policy Institute

Refugees and Asylees, DHS

Refugee and Immigration Services, Catholic Charities

Population Change by State, Pew

Ashley D. Keenan – Ashley is an editor of The Portland Townsman, writer on urbanism, local small business-owner, and Maine native. Her work primarily covers the national housing crisis, building sustainable and livable cities, responsible market economics, and New England culture and history. She lives in Portland with her fiance and can be personally reached at ashley@donnellykeenan.com.