This is part one of a series of articles from Markos Miller on the past, present, and future of Franklin Street, Portland’s most divisive throughway.

In the 18th century, today’s Franklin Street was known as Essex Street, which ran from Back Street (now Congress) to Fore Street, terminating at Tyng’s Wharf. An 1823 map of Portland showed a new street named Franklin Street, which was aligned with Essex Street, extending north from Congress Street to Back Cove (which sat just past Oxford Street). In the 1850s, Commercial Street was built, and the Essex/Franklin Street was extended out into the harbor onto the new Franklin Wharf. The entire street was christened Franklin Street, from Back Cove to the waterfront.

Histories of individuals or communities are often recounted, but it’s worth it, if you live here, to contemplate the history of this road. To understand the history of Franklin Street is to gain crucial insight into the history of Portland, and what’s more, into the state of Portland today. To get there, however, one must start at the beginning.

Portland’s Great Fire of 1866 destroyed nearly every building on Franklin Street, sparing only the southernmost block and the structures built on recently filled land north of Oxford Street. As the city was rebuilt, Lincoln Park was created between Pearl and Franklin Streets; it was Portland’s first public park, and conceived as a firewall. Lincoln Park established the redeveloped Franklin Street as a desirable place to live. The street was largely residential, with small businesses at the corners of cross-streets. The majority of homes were single-family, built in the Italianate and Second Empire styles. Older homes that remained on the street north of Oxford Street were predominately in the older Federal and Greek Revival styles.

In the later 19th century, many of Portland’s upper middle-class families relocated to the newly developed West End neighborhood, and the single-family homes along Franklin Street were gradually converted to apartments. By the early 20th century, immigrant communities were beginning to settle into the neighborhoods along Franklin Street. Italians founded “Little Italy” near the southern end of the street, with Jewish, Armenian, and other families residing further up the corridor. These communities created local businesses and established houses of worship. Well maintained homes along tree-lined streets are shown on the 1924 Portland tax photos.

The neighborhoods of the Portland peninsula had deteriorated significantly by the 1950s. The lack of investment during the Great Depression combined with postwar shortages in labor and building material had taken a toll. “Maintenance-free” siding materials had obscured much of the architectural detail and character of some buildings along Franklin Street, and subdivision into smaller residential units had increased the density of the neighborhood.

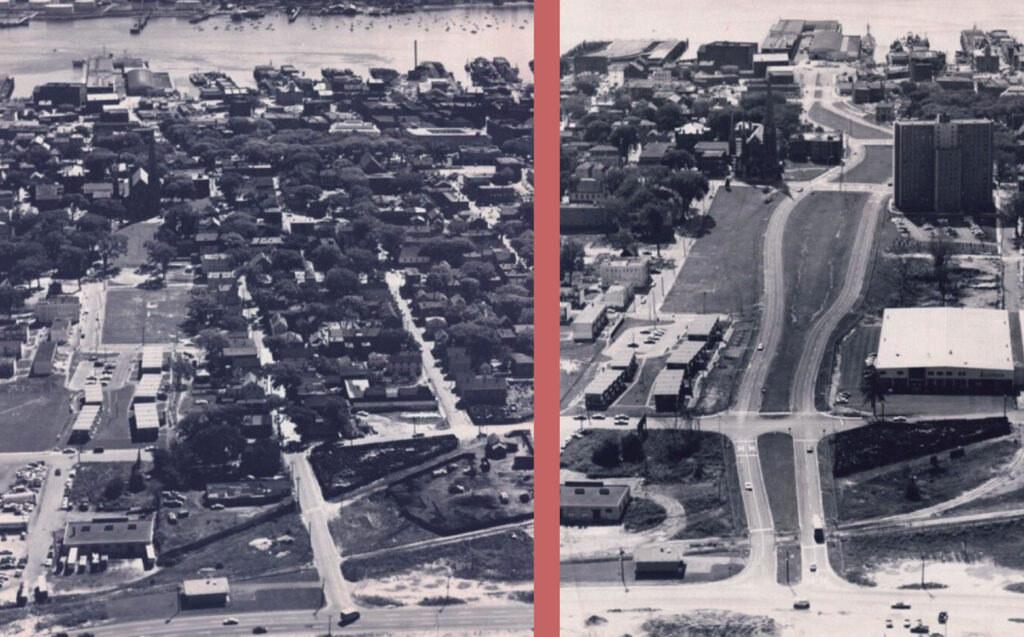

In 1958, Portland’s slum clearance authority classified many of these neighborhoods as “slums.” The ‘Little Italy’ neighborhood, bordering Franklin, was demolished. The many buildings along Vine, Deer, and Chatham Streets were deemed ‘substandard’ and razed, displacing 64 families, 28 individuals, and 27 small businesses. That year another phase of “slum clearance” targeted the mixed-use block between Lancaster, Pearl, Somerset, and Franklin Streets – where Whole Foods now sits – making way for the ‘Bayside West’ project. This area was home to more than 85 residents, and included 44 housing units and at least 31 households. Another 54 units were razed for the “Bayside Park” urban renewal project across Franklin Street. Now called “Kennedy Park,” this area’s through streets were truncated in an attempt to limit access to outside traffic. Later, the low-income housing built here was fenced off with chain link to keep pedestrians out of the corridor. What remained of Franklin Street was razed to the ground beginning in 1967. At least 100 structures were demolished and a still-unknown number of families dispossessed.

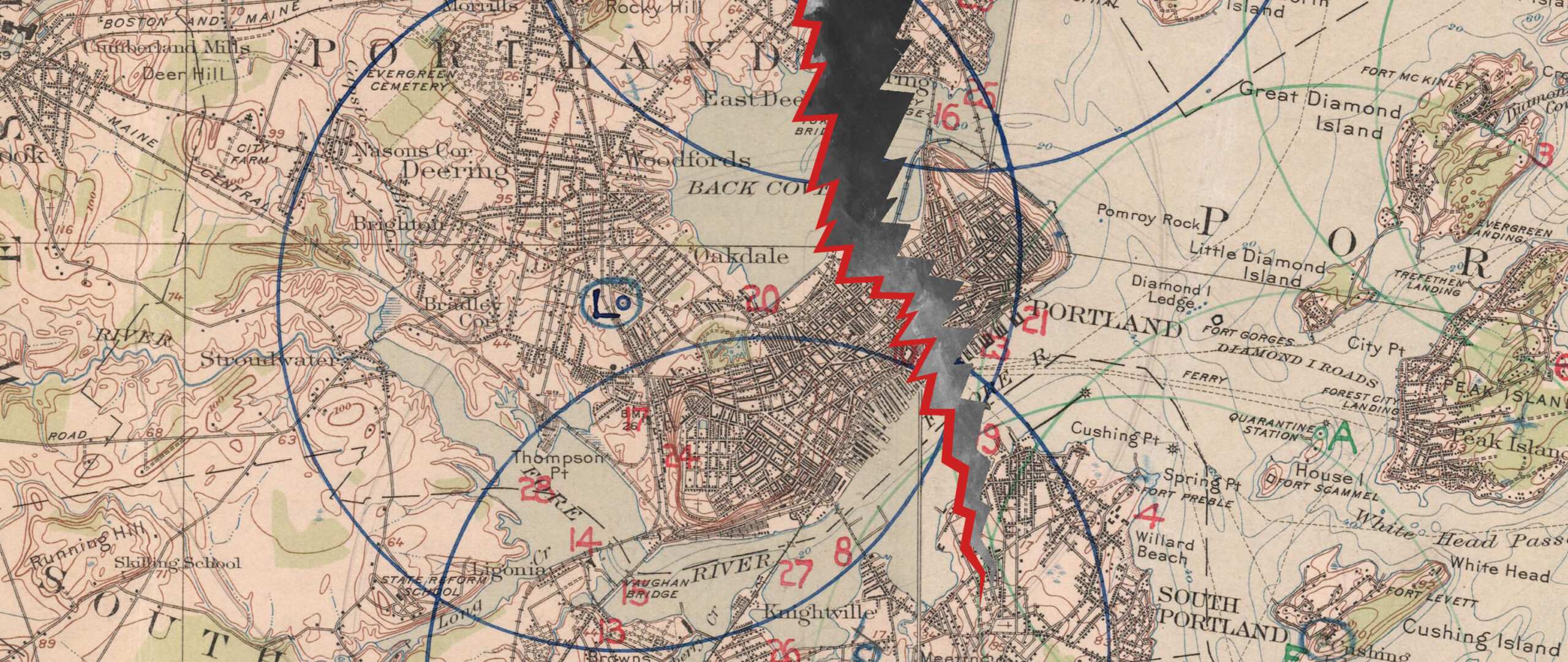

Franklin’s current design – two lanes southbound and two lanes northbound separated by a wide undeveloped median – is only the first phase of the original Franklin Arterial plan. Connections between the east and west sides of Lancaster, Oxford, Federal, and Newbury Streets were severed in order to promote the uninterrupted flow of automobile traffic. The arterial plan, as envisioned in Victor Gruen’s “Patterns for Progress,” called for future high-speed lanes to be tunnelled underneath Cumberland and Congress Streets in the center median. It was projected that traffic growth would necessitate this by the late 70s or early 80s.

Franklin Street, and other Portland streets, were connected to the newly built Interstate 295 in 1971. The Franklin Street Arterial was but one part of a larger transportation plan for the Portland peninsula. “Patterns for Progress” envisioned a ring of arterial roadways like Franklin Street running around the peninsula. Other signs of this plan include Middle Street, which had gently turned up towards Monument Square, being redirected west, and connected to Spring Street. The widening of Spring Street had also begun, but when it became clear that the bulldozers would continue towards the wealthier West End, residents protested until the urban renewal plan was abandoned. Of course, it was too late for the East End neighborhoods.

The Franklin Street arterial is now a major corridor for traffic entering the east side of the Portland peninsula from I-295. This new Franklin Street was designed to function like a highway, while the original Franklin Street was an integral part of the diverse neighborhoods in Portland’s East End. It was once a regular two-lane neighborhood street running north-south across the peninsula. The cross streets of Oxford and Lancaster had connected East Bayside and West Bayside, with Anderson Lane providing another connection to the east. On the south side, overlooking Portland Harbor, Franklin bordered the “Little Italy” neighborhood, home to some of the poorest of the peninsula’s residents, but also a vibrant and cohesive neighborhood community.

Today, Franklin Street is a dividing rupture through the peninsula. The road poses severe challenges for pedestrians and bicyclists, and is considered one of the most significant barriers to safe and effective movement of pedestrians in the city. Franklin Arterial has never been reintegrated into the fabric of the urban environment. It is a place only for cars, not people; and even then, it is not that safe for drivers either, with a number of intersections classified as “high-crash” areas with other safety and mobility issues for vehicles. Other than crosswalks at the few intersecting streets, alongside temporary sidewalks built 15 years ago, there is no pedestrian infrastructure. The long blocks force people to walk up to a quarter-mile out of their way to reach their destination on the other side of the street.

Nevertheless, the old cross streets have never died. Holes in chain link fences and footpaths worn into the median attest to the local residents’ persistent demand to cross, even at great hazard. Furthermore, Franklin Street has no accommodations for public transit. It presents a deep tear in the traditional street grid, and along with a mixture of dead-ends and one-way streets, prevents bus access and easy circulation to adjacent neighborhoods.

Franklin’s configuration presents a decisive psychological barrier to non-automotive travel, in addition to being a substantial physical barrier. The street’s wide footprint and unbuilt roadside are out of scale with the surrounding urban landscape, creating a “no man’s land” effect. Only two buildings face today’s street, where once dozens of homes and businesses did. The city has largely, literally, turned its back to Franklin. It is a clear and distinct rip in the neighborhood fabric of the area, creating an obvious and unmistakeable border.

In 2006, Portland completed the Peninsula Traffic Study. The purpose of this study was to project future traffic patterns based on a maximum build-out of the peninsula, all while strengthening some of the pedestrian amenities and open space assets that had been degraded by arterial expansions in the ‘60s and ‘70s. The Traffic Study was based on a ‘worst-case scenario’ projection of traffic growth and sought to shift this projected traffic onto Franklin Street. In order to accommodate this increase in traffic, Franklin was envisioned to be doubled in width, with four lanes of traffic each direction. Taking a cue from Gruen’s plan, the Peninsula Traffic Study considered sunken through-lanes running under Cumberland and Congress Streets. The study also failed to address obvious pedestrian needs and other economic and community opportunities in the corridor. Some have suggested that the extreme recommendations of the study were meant to be a wake-up call about the costs of increased road widening and reliance on an auto-centric transportation system. If this is the case, no one in leadership took the hint.

The study’s recommendations were widely rejected by the community. The assumptions underlying the traffic projections were questioned, costs were deemed prohibitive, and the neighbors found the widened roadway concept unacceptable. The City Council tabled the study after extensive feedback from neighborhood organizations and other groups. The Traffic Study had failed to address needs and opportunities other than the movement of vehicles, but it did draw greater attention to these deficiencies, and provoked a community debate about how Portland should sustainably move people on and off of the peninsula.

Discussion about the future of Franklin Street continued in the community. Architalx, a local architecture and design non-profit that focuses on raising awareness of quality design, held a local design competition titled “Lost Sites,” which selected ten ‘lost sites,’ or underutilized/abandoned locations on the Portland Peninsula, to be re-evaluated by the design community. Most of the submissions reenvisioned Franklin Street. The event helped stimulate a community brainstorm to see beyond what currently existed in the corridor and to envision a more vibrant roadway that serves multiple communities while connecting the peninsula.

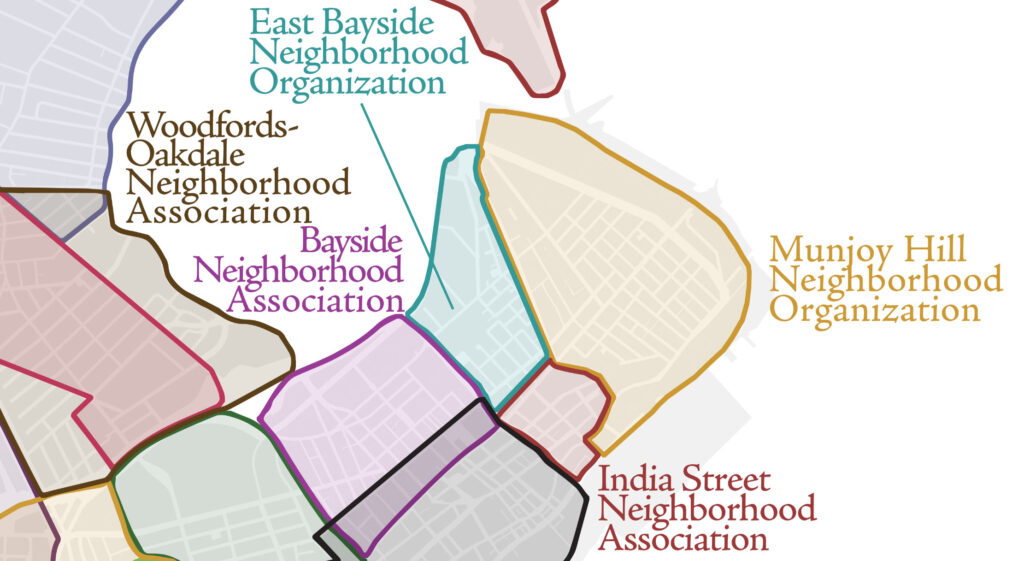

In 2007, the Bayside Neighborhood Association and the Munjoy Hill Neighborhood Organization formed the “Franklin Reclamation Authority” (which, despite the name, was a private organization.) The group held a community workshop, “Re-Thinking Franklin Street Arterial.” With 70 members of the public attending and city staff on hand as observers, participants worked in small groups, following a consensus-based process to create a Problem statement and a Vision statement for Franklin. The workshop, and the outcomes were documented in a report and shared with then City Manager Joseph Gray, and others in the community. This work was welcomed for its inclusive process and alternative vision for Franklin Street, and led to the creation of Portland’s Franklin Street Redesign Study Committee the following year.

This committee inaugurated today’s ongoing effort to reimagine and rebuild Franklin Street to better match the needs of the community. In the next part of this series, I catalog the progress of this endeavor, and how the city arrived at the Master Plan being put into action today. We can also look into the future of Franklin Street, and what challenges still remain. This solitary road slicing through the peninsula is, both literally and figuratively, at the heart of the peninsula, and the debate about what Portland ought to be.

Markos Miller – Markos is a founding member of the Franklin Reclamation Authority and served as the co-chair of both phases of the City’s Franklin Street Redesign Committee from 2008-2015. He is an educator, community organizer, and resident of Munjoy Hill.

Thank you for writing this. Very informative, and I look forward to following this series.

Good information. As a sometime visitor to Portland, I’ ve often wondered what led to its development. Thank you gor your research. I look forward to more information about this.