This article is the second in a three-part series on 2023’s Question A. As disclosure, Ashley Keenan lives in an apartment covered by the current rent control ordinance.

Portland, Maine has one of the strongest, if not the strongest, rent control laws of any municipality in the country. Whether this is a point of pride, dismay, or indifference varies significantly from resident to resident, but in the three years since it has taken effect it has undoubtedly become a fixture of local life in a way few other municipal ordinances so obviously become. As its supporters proudly resound, it offers a significant degree of predictability to Portlanders who rent a covered unit in which to live; we (this author is one such renter) can rely on the fact that our largest single expense will only rise in cost each year at a relatively small rate. Its detractors, just as self-righteously, point to darkening statistics in rental vacancy, availability, and non-subsidized construction and point to this law as one of its causes.

For a thorough explanation of how Portland’s rent control ordinance works, see the previous piece in this series.

For the third time across three elections, Portlanders are being asked to amend this hugely controversial law. Question A asks, broadly, voters whether they’d like to exempt “small landlords” from the punishing effects of rent control on their bottom line. What, precisely, is proposed to be changed? What effect would these changes have? What is a “small landlord”? Am I going to face a rent spike?

Question A Explained

The proposal, which can be found in full here, is a brief read. It amends just two subsections of the rent control ordinance’s text, 6-231 (Applicability) and 6-232 (Definitions.) The first of these identifies rental units owned “in whole or in part” by a person or entity who owns 9 or fewer non-exempt units in Portland (and isn’t an “affiliate” of one who owns more) as exempt from the ordinance. Herein, this carveout will be called the “Small Landlord Exemption.” The second defines what an “affiliate” is, quite broadly.

A unit which is exempt can have its rent price freely set by its owner, so long as it complies with general state and municipal law.

This seems like a quite straightforward change, and it is – but there remains some subtle ambiguity that may not be immediately understood, and such gray areas are the breeding grounds of misinformation and confusion.

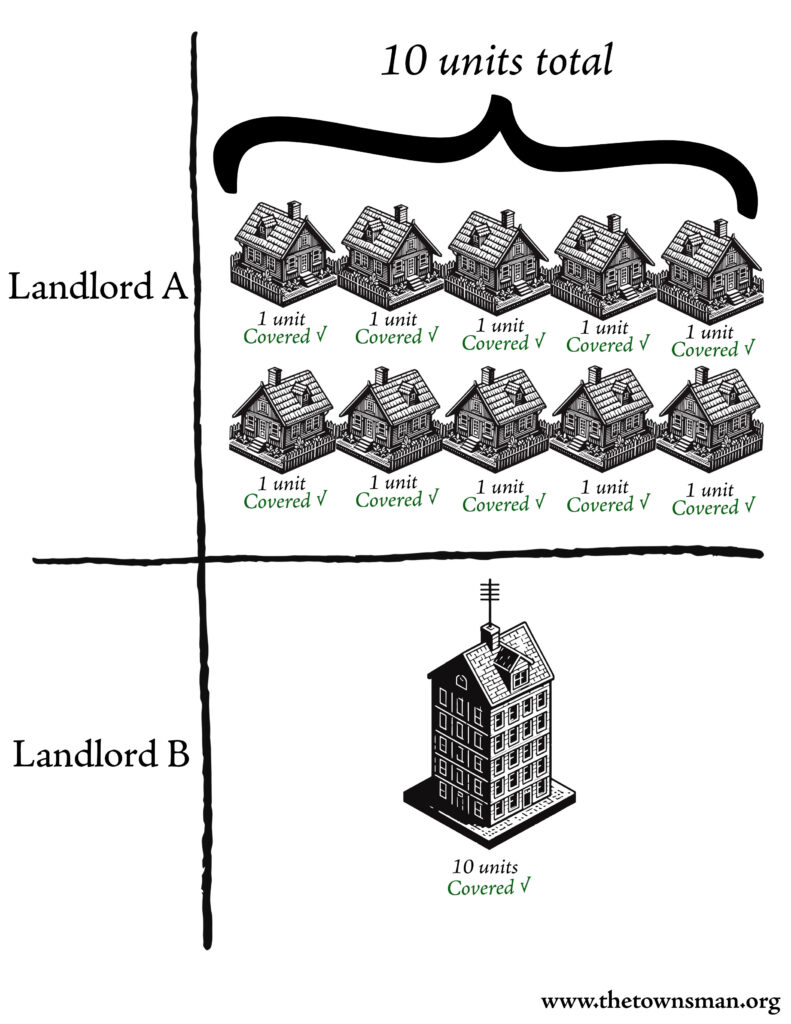

First, the “count” of owned units applies to all units owned in Portland, not just those in the same building. A unit-owning person or entity (which I will herein be calling simply a ‘landlord’ even if the landlord is a business entity rather than a person) which owns 10 units in one building and a landlord which owns 10 units in 10 different buildings are treated exactly the same, and neither would receive the Small Landlord Exemption.

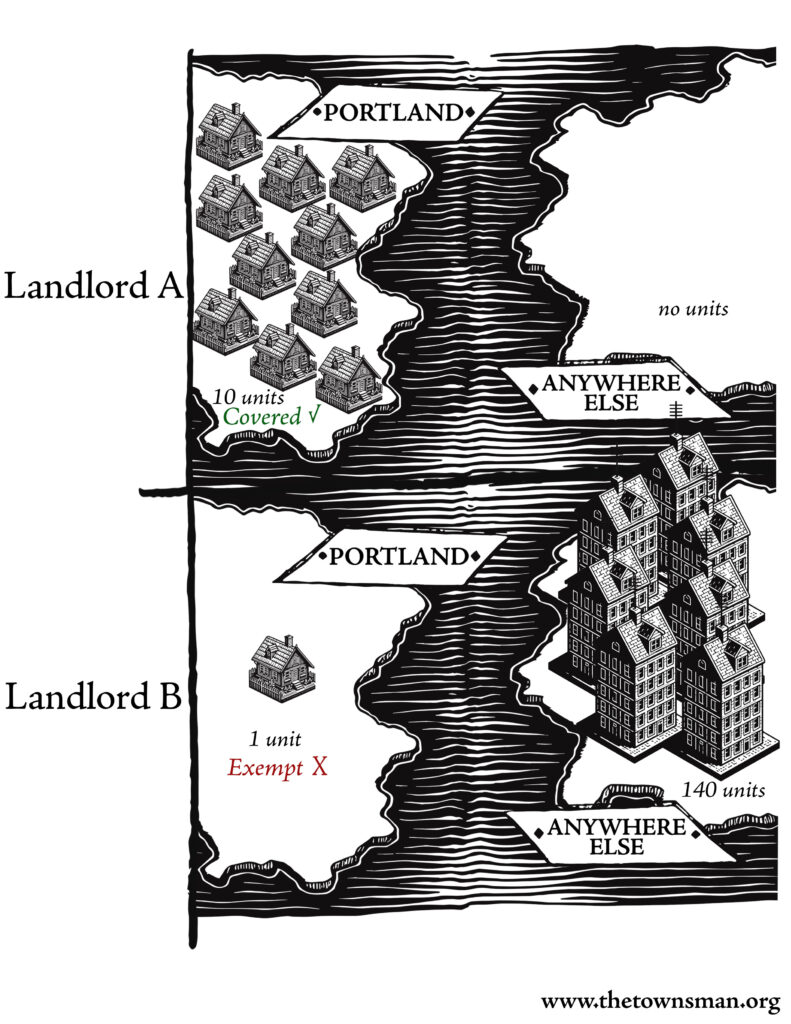

However, the “count” only includes units that are physically in the city of Portland. This means that the ordinance is completely blind to what units a landlord may or may not possess outside of Portland. A landlord with many units in other towns will qualify as exempt if they own fewer than 9 in Portland, and a landlord with 10 units in Portland will not qualify even if they don’t own any other units at all.

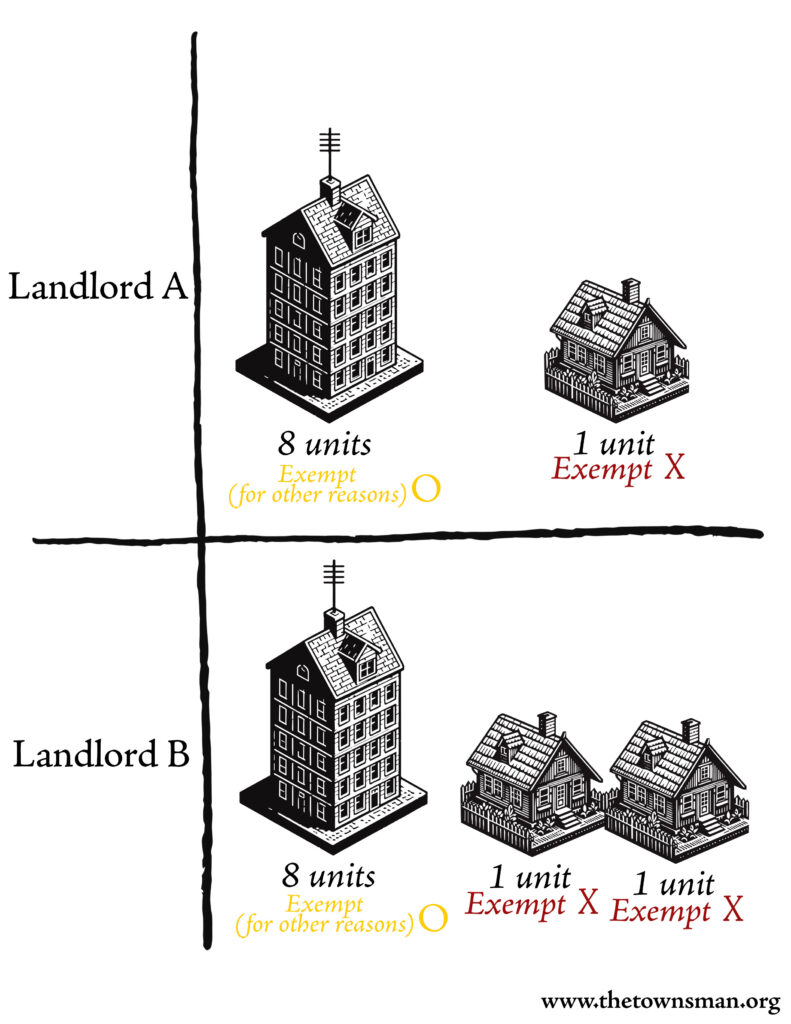

To further clarify, the “count” only includes those units that are not otherwise non-exempt. For example, if a landlord owns 8 units which are exempt for other reasons, (e.g. they’re college dormitory units, or ADUs,) and 1 ordinary non-exempt unit, the ordinance only “sees” that they own 1 unit. The landlord is free to add up to 8 more non-exempt units before losing the Small Landlord Exemption.

So, with all this in mind, it’s exactly what it says on the tin. If a landlord owns less than 10 otherwise non-exempt rental units inside of Portland itself, those units are exempt from the rent control ordinance. Unlike last June’s referendum, which had a number of ambiguities hanging over it due to imprecise drafting, this November’s referendum is quite straightforward and simple. Are there any lingering questions about this one at all?

“In Whole or In Part” – Loopholes and Conspiracies

Just one.

Refer to the following selection from the text of Question A:

Any rental unit owned, in whole or in part, by an owner where that owner and all affiliates of that owner…

Question A, November 2023

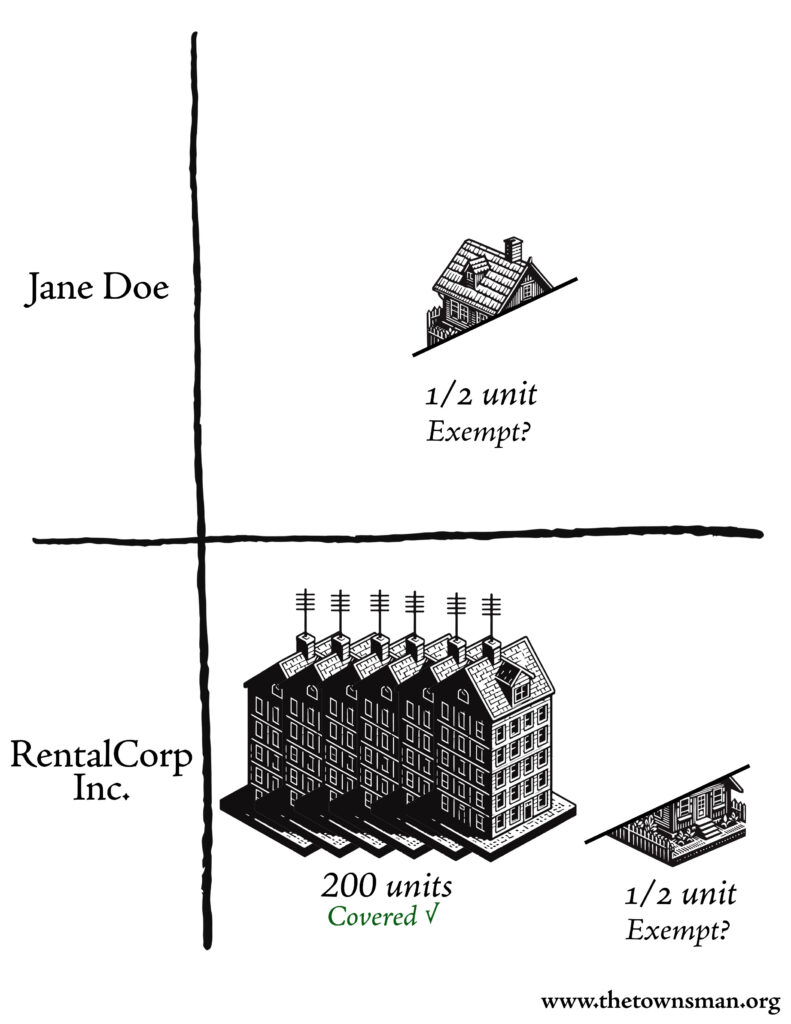

Emphasis added. If you have the sort of mind inclined to look for technical loopholes, this parenthetical may have needed no emphasis at all. An immediate possibility springs to mind: Could a “small landlord” own half (or less) of a rental unit otherwise owned by a “large landlord” and, by so doing, render the unit exempt from rent control for the benefit of all of its owners?

Answer: No… probably.

The reason why this genius stratagem for evading the ordinance probably wouldn’t work is in the second part of the selected text:

Any rental unit owned, in whole or in part, by an owner where that owner and all affiliates of that owner…

Question A, November 2023

“Affiliate” was previously not a defined term in Portland’s code, so the drafters of the question had to define it themselves. And, to their credit, they did so quite broadly. Below is a (non-exhaustive) list of persons who would be considered an “affiliate” of a landlord:

- Spouse

- Domestic partner

- Conservator

- Guardian

- LLC which landlord is a member or manager of

- LLC which landlord’s spouse is a member or manager of

- Any member or manager of an LLC which landlord is a member or manager of

- Any member or manager of an LLC which landlord’s spouse is a member or manager of

- Corporation which landlord is an officer of, director of, or otherwise in control of

- Corporation which landlord’s spouse is an officer of, director of, or otherwise in control of

- Business partner

- Business partnership including landlord

- Any like affiliate of someone considered an affiliate, (e.g. a spouse’s business partner)

The definition is quite comprehensive, and also serves to dispel the loophole that a landlord could just open up a slew of LLCs to own 9 units each. This is evidently accounted for. But to address the “in whole or in part” loophole at hand, we’re most concerned with those last few examples, concerning a business partnership.

Business law is, obviously, a very complex subject. The gritty details of discovering implied partnerships, beneficial ownership, etc. are far beyond the scope of this article, (and the faculties of this author.) Be assured also that this should not be taken as legal advice. But, in short, while LLCs and Corporations are business entities which are quite formal in their creation and existence, Partnerships can be more informal, and even found to be in existence by courts of law without any concrete documentation. (Varies by jurisdiction.)

In other words, if two people agree to work together to turn a profit, they may be found to be in “partnership” even without signing any sort of agreement establishing one as such.

As a result, if RentalCorp, Inc. and Jane Doe conspire to have Jane, who owns no other rental units, come into possession of partial shares in 9 of RentalCorp’s units… this is probably an implied partnership, and would not make those 9 units exempt from the rent control ordinance. That is, assuming their scheme is noticed.

But, just because this sort of overt conspiracy goes against the letter of the law, that doesn’t mean this language couldn’t result in some puzzling situations. Imagine, for example, if a mother passed away and left a single-unit rental property in Portland to her two adult children, neither of whom own any other units, in two equal shares (in jargon, suppose a joint tenancy.) Further, let’s suppose one of these children sold their share to RentalCorp, which naturally seeks to collect the one half of the rental profits their share entitles them to. Because the other child owns less than 9 units, (just half of 1 in fact,) this unit could be found to be exempt from rent control despite co-owner RentalCorp owning hundreds of other units in the city.

While this may look like a partnership, a glance at the relevant statutes (Title 31 Chapter 17) casts some doubt over this. “Joint tenancy, […] joint property, common property, or part ownership does not by itself establish a partnership, even if the co-owners share profits made by the use of the property”; “A person who receives a share of the profits of a business is presumed to be a partner in the business unless the profits were received in payment: […} of rent.” §1022, emphasis added. While any whiff of intentional structuring by RentalCorp or its real-world peers would be looked upon with wicked disapproval by any court of law, the possibilities certainly seem open.

How would this actually play out in court? Difficult to say, and it’s a pretty unlikely scenario anyway. But this sort of legal ambiguity is a common feature of citizens’ initiatives. Even the original rent control ordinance, plagued by loopholes, had to be tightened up by a further referendum just two years later.

With this one oddball loophole out of the way, however, the thrust of the proposal remains quite simple. But what would it mean for Portland’s renters?

Ramifications

You have, especially if you’re also a renter in Portland, picked up on the most obvious consequence of Question A, should it pass. Any tenant currently renting a unit from a “small landlord,” as designated, would immediately cease to be covered by rent control’s restrictions against market-rate adjustments of rent prices. While the reality would surely vary greatly between individual circumstances, it would be reasonable to expect significant increases in rents as leases come up for renewal over the next year.

This anxiety is felt keenly, and it is further kindled by the activism of the rent control ordinance’s originating organization – the Maine Democratic Socialists of America. The Maine DSA (most active in local Portland politics) has been able to reuse a lot of their signs this election season, fresh off of beating back the vaguely similar Question A back in June.

Seeking to make the issue immediately real for many renters, the DSA, in cooperation with an independent web developer, released this fantastically useful tool: https://no-on-a.anvil.app/

If you enter your address in this website, it will respond with a (probably correct) determination of whether or not your unit will be affected by this change. If you, for any reason, aren’t sure whether your landlord qualifies as a “small landlord” for the purposes of this proposal, wonder no longer. I’m fortunate in that my landlord owns far too many units to qualify, but it’s obvious that there are many, many units in Portland which would be made exempt by this referendum.

But, how many?

Tools like the DSA’s only further press the urgency of this question. There is much information which is publicly available, or available upon request, regarding Portland’s housing stock… but trying to make sense of it in concert is a daunting task. Even for the best datasets which exist, most are incomplete, outdated, littered with bad data, or otherwise imperfect. Any estimate will only ever be an estimate, and the quality of the guess is inherently limited by the quality of the underlying data, that is to say, not ideal.

Matt Walker, member of the City of Portland’s Rent Board and the Trelawny Tenants’ Union, and I like to think a friendly acquaintance of mine, unsurprisingly was unintimidated. Splicing together datasets from across various sources, (including at least one which is not available to the general public,) manually refining the datapoints, and making a few educated assumptions, Mr. Walker was able to reach a plausible estimate.

The key tactic here – easier said than done – is to connect each individual rental unit on the market with a landlord’s address connected to their tax bills. This method is the most likely to catch “affiliates” which otherwise aren’t obvious, and can mostly identify those units which belong to owners with more than 9 units in Portland. This involves a lot of manually sorting through data for nearly 20,000 units.

Even this estimate, however, isn’t without its faults. It may result in overcounts, for example by missing “affiliates” or not detecting when landlords use multiple addresses. But it also may result in undercounts, mistaking property managers (which work for many landlords) for individual large landlords, or by mistakenly identifying “affiliates” where there are none. Furthermore, Mr. Walker comes into this battle with an avowed agenda – opposing Question A and the landlords who support it, (in his internal spreadsheets, Question A is even referred to as the “Landlord Referendum.”)

No approximation could ever be perfect, and the motivation of Mr. Walker shouldn’t be overlooked. Nevertheless, after reviewing his methodology and the data for myself, I believe this to be at least a plausible guess; I have enough confidence in it to publish the result here. Others who have attempted to riddle out their own estimates have reached similar conclusions. So, what’s the verdict?

40%, approximately, of currently non-exempt units, would become exempt should Question A pass, or, more than 4,200 units.

To place this in an even broader context, counting all rental units that the Housing Safety Office has data for, there’s about 18,000 rental units in Portland. Right now, about 60% of these are covered by the rent control ordinance, and about 40% (unrelated number) are exempt. Should Question A pass, the center of gravity would swing across the median; approximately 36% of units would be covered, with 64% being exempt.

In other words, even if we assume a massive margin of error, if Question A passes then a heavy majority of Portland’s rental units will be exempt from the rent control ordinance.

To compare with the 40% of units which would immediately become exempted from rent control, had this past June’s Question A passed, 0% of currently-occupied rental units would have become exempted.

For privacy concerns, I have elected to not publish raw data which was provided to the Portland Townsman by Mr. Walker. However, if any interested parties would like to examine this information, I encourage you to reach out to me personally at ashley@donnellykeenan.com.

Stakes and Ladders

With the understanding of how the mechanics of Question A are constructed, and with a reasonably accurate view into what the impact of this would be on Portland’s renters, readers should feel confident in having enough information to form their own opinion. Rent control’s detriments are well-documented by economists with virtually zero dissenters among them, and there’s plausible reason to believe that Portland is already suffering some of its effects. But to suddenly, instantaneously remove rent control restrictions on nearly half of all tenants who currently count on them will surely have a massive impact on our city’s communities. Is Question A the answer?

Ashley D. Keenan – Ashley is an editor of The Portland Townsman, writer, local small business-owner, and Maine native. Her work primarily covers the mechanics of local government, the ongoing housing crisis, responsible market economics, and New England culture and history. She lives in Portland with her fiancé and can be personally reached at ashley@donnellykeenan.com.