This opinion is the third and final article in a three-part series on 2023’s Question A. Unlike the previous two articles which were objective reports, this is a subjective editorial expressing the opinions of Ashley Keenan alone.

As disclosure, Ashley lives in an apartment covered by the current rent control ordinance.

Portland’s rent control ordinance, as it stands today, is a millstone around our necks. It is, only somewhat arguably, the strictest active rent control ordinance of any city in America. We are venturing the well-being of Portland’s citizens on a very risky experiment.

I believe that some form of rent stabilization is necessary to prevent the shattering displacement of individuals and communities in Portland, and I am not surprised that the city voted in favor of a referendum enacting one. But this issue demands those most unfashionable of responses – nuance and moderation. Preventing sudden leaps in rental costs during an unprecedented housing crunch is a simple moral good, but worsening the underlying crisis by stifling home-building and spreading out growth to the outer suburbs is a cure as hazardous as the disease. We should not repeal rent control, but if Portland is to recover its role as Maine’s leading light in equity and prosperity, we must reform it.

But Question A is not the reform we need. It would make things worse.

The Consensus of Economists and Why You Should Care

First, it must be emphasized that rigorous rent control is uniformly considered to be a deeply destructive force by, without meaningful exception, every single expert on the subject. “The fastest way to destroy a city other than bombing,” or so goes the famous quote by former Nobel committee chair Assar Lindbeck. Meta-analyses of the field found no population of economists (an argumentative and contrarian bunch!) who supported rent control measures in 1992 and 2009. In a 2012 survey of 42 top economists found only one (a non-specialist) who was even willing to cautiously disagree with the notion that rent control was always negative. This was the most one-sided issue in the survey, weighted for confidence. A Brookings review in 2018 discusses the continued, universal revulsion among economists of both orthodox and heterodox tendencies towards rent control. Not a single economist of note supports any policy resembling that which Portland enacted in 2020 and 2022.

Some will tell you different. The Maine Democratic Socialists of America, (which really ought to be called the Portland DSA, judging by their area of activity,) cited a study from the University of Southern California staking out a cautious contrarian take on rent stabilization… but even in this report, if one takes the time to read it, the severe provisions of Portland’s ordinance are specifically advised against. The DSA cited a study in support of their policy which explicitly opposes their policy. A similarly infamous 1995 study by contrarian economist Richard Arnott reached a similarly modest conclusion. The literature in favor of rent control is so thin that ephemeral blog posts from auxiliary orgs like the Othering & Belonging Institute (formerly the Haas Institute) are cited in what can only be described as desperation.

But, why should anyone care what these eggheads think? Economics as a discipline hardly has an unblemished track record, and what matters is keeping a roof over needy people’s heads, not maximizing profits for shareholders. As one of those people who is kept under a roof by the rent control ordinance, I am in fact deeply sympathetic to this point of view. But it’s worth stepping past just citing economists as authority figures and reaching in to understand why rent control is so starkly villainized.

Running through the rap sheet of observed, measured effects is usually enough to scare straight most local policy wonks. Introduction of rent control ordinances led to an increase in both overcrowding smaller apartments and empty-nesting in larger units. Rental units are permanently warehoused – empty – off the market when maintenance costs outpace income. Business investment (in unrelated markets!) drops off, and economic prospects for tenants decrease even considering their savings on rent. Conversion of rental units to condos increases even in the face of upfront costs to the landlord. Tenants with ‘soft’ factors that work against them in rental applications (e.g. criminal record, pet owner) are more systematically excluded from open units. Multi-unit buildings are consolidated into fewer-unit, or even single-unit, structures for sale as homes. Corruption, extortion, intimidation, and black-market housing transactions increase in frequency, especially within (and at the expense of) immigrant communities. The list goes on.

There are even effects which haven’t had the opportunity to be thoroughly studied precisely because rent control ordinances which don’t account for them are so rare. For example, even in the rent control regimes (both present and historical) which are considered to be archetypal examples of overreach, it’s rare to see a rent control ordinance which doesn’t make exemptions for new construction, so as to not discourage home-building.

But Portland’s ordinance doesn’t exempt new construction.

If nothing else, should Portland’s voters and representatives choose to keep our rent control ordinance essentially as-is, it will be a very valuable opportunity for economists to study such an outlier system.

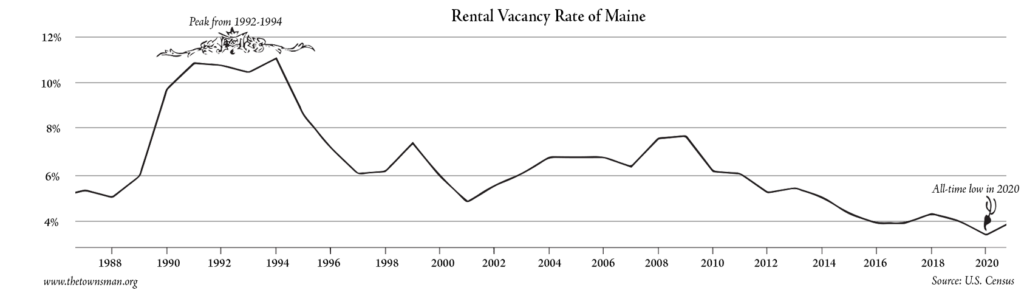

Needless to say, however, the prognosis is grim. Greater Portland is in a deep housing shortage, with rental vacancy rates at multi-decade lows as there’s simply not enough units to go around. In a famine, food becomes precious. In an oil crisis, gasoline prices skyrocket. In a housing shortage too, the prices can only go in one direction. To address housing costs equitably and sustainably, one needs to address the shortage. Despite this, and despite what some will baselessly suggest, over the last 15 years Portland and its suburbs have been downright lethargic in building new homes for people.

While there are many other factors which may prove (the data is as yet insufficient to speak confidently) to be more impactful in this sphere, the fact that any new rental units constructed will be held below inflation in price increases is a massive disincentive to build any but the highest of luxury units. Why not choose Scarborough instead for anything else? Contribute to the car-dependent sprawl engulfing the outer suburbs.

Even in the face of the mountains of evidence that Portland’s rent control ordinance is designed for failure, there will be those that simply deny it. To delve any deeper into such persons’ motivations would be an exercise in psychology I opt not to entertain. But for those of us willing to engage with the academic consensus, it leaves us in an unenviable bind.

If we accept that Portland’s rent control needs to be reformed, is this Tuesday’s Question A the way to do it?

No.

Why Question A Isn’t It

So in response to these problems, how does Question A purport to address them? By exempting landlords with nine or fewer units.

I cannot stress this enough: This is not a reform; this is a carveout.

Instead of addressing the underlying economic and social problems which the housing shortage and rent control pose, this referendum seeks only to shield a certain cadre of landlord from its most direct impacts. The overall economic detriments of rent control will be only slightly mitigated, (for reasons of simple scale,) while up to 40% of rental households will face leaps in rent prices and possible displacement.

Will Question A address the issue of disincentivizing new construction? No, in fact it will add to that problem a slight incentive to build fewer, less dense units instead of the efficient and sustainable housing which Portland’s renters need. Building homes in Portland will remain an unattractive option compared to our neighbors.

Will Question A address the issues of deleterious socio-legal effects around the scramble for too few units in a shortage? Not at all, it will continue to exert a strong pressure on landlords to make “safe bets” on privileged applicants for the limited available housing. It’s unclear what effect it would have on black market risks, but I doubt it would be a significant improvement.

Will Question A address the issue of economic investment declining, and tenant prosperity decreasing? How could it? If the only landlords able to act freely are small entities axiomatically unreceptive to outside investment, Portlanders will continue to suffer the hits to our income/expenses ratio.

Will Question A make it easier to address these issues in the future? Quite to the contrary! If a significant chunk of Portland’s professional landlords receives arbitrary exemptions from rent control, it would become even more difficult to establish consensus for fair reforms.

So, what does Question A offer?

Well, if you’re a “small landlord,” you will be able to charge more for your units. If you’re not a small landlord, it’s far from clear what this unprincipled exception has to offer you. I believe this simple fact helps to explain why campaigning for this referendum has been so relatively anemic compared to similar efforts in the past, and why I ultimately believe it will fail.

The obvious motivation, (beyond simple self-interest,) is an “anti-corporate” feeling. It’s the same feeling which motivates people to prefer small businesses to large chains, or mom-and-pop restaurants to franchisees. It’s a natural feeling, and usually a positive one – but this feeling should be examined routinely, lest it lead you wrong. I like going to small restaurants and businesses when the atmosphere is warmer, the experience more authentic, the connection to community more real, and the product superior. In addition, the dollars I spend are more likely to stay in the local economy, ultimately to all of our benefit.

But not every small business is like this. Plenty are just more expensive and less convenient versions of the experience I can get at a nationwide corporation. Any plenty of others are just… bizarrely irrelevant. How this city sustains its high-end, boutique artisan galleries which litter the peninsula, I’ll never know. I do know that I will never be purchasing the handcrafted porcelain bowl for $800.

In the case of landlords, are “small landlords” somehow more intrinsically virtuous? As someone who’s rented from both mom-and-pop landlords and corporate management companies in Maine and Vermont, I’m not inclined to think so. Small landlords are sometimes kind, understanding, and handy in a way that a corporate landlord will never be… but there’s an opposite side to that bell curve. The most nightmarish landlord experiences which I or my loved ones have had were also at the hands of “small landlords.” By contrast, corporate landlords are usually much more predictable; they won’t cut you much slack but they won’t give you undue grief either, and one can reliably engage with them professionally.

If someone, (perhaps after one of those bad experiences,) prefers a reliable-if-cold corporate landlord to engaging with a local triplex owner, who are we to tell them that they are wrong to do so? If a landlord with nine units is successful and fair-dealing, why would we be opposed to them operating more units? Why would we want to incentivize landlords with ten or twelve units to consolidate them and become an officially “small” landlord?

Already in the ordinance, those landlords who rent out three or fewer units in the building they live in are exempted from rent control. This carveout wouldn’t be helping your grandmother who rents out her basement; this carveout would be helping a minority cadre of professional landlords. It’s utterly opaque to me why professional landlords who have declined or failed to acquire more than nine units should be so especially rewarded.

In short, while helping “small landlords” may sound appealing in passing, it’s hard to riddle out any tangible benefit to the city or its inhabitants other than those who are, themselves, “small landlords.” Rent control would still need reforming, but now it would be further bedeviled by entrenched, protected minority interests.

Question A solves nothing.

What Reform Might Look Like

So, if not Question A, then what might a real reform look like? I believe that a good rent control policy reform would need to satisfy three criteria:

- Protect current tenants from displacement

- Incentivize the construction of new homes, including rental units

- Point towards a sunsetting of rent control provisions as the market normalizes

By meeting these three points, a reform could prevent mass displacement in the short-term, work towards treating the underlying causes of the housing crisis in the medium-term, and wind itself up as a relevant law in the long-term.

It should be noted at this point that Question A fails all three points.

A better law might keep all current tenants under rent control protections, only raise prices during the vacancies which follow voluntary departures, create a bonded exemption to all newly built homes, and ultimately result in a reset to general market rates after so many turnovers.

If this sounds somewhat familiar, this isn’t too dissimilar from the reform proposed this past June, also called Question A. The June referendum, despite being the product of the sinister Rental Housing Alliance, (f/k/a the Southern Maine Landlord Association,) was an almost shockingly moderate compromise. It was somewhat sloppily drafted, but seemed in all respects to be an earnest, good-faith effort by an industry organization to meet rent control halfway. It would have affected zero current tenants, while this November’s Question A is set to affect up to 40% of current tenants. Indeed, this November’s referendum is by nearly any reckoning a far more clear-cut cash-grab by a group of landlords. Yet because it has a whiff of “anti-corporate” feeling about it, this is not how it is perceived by many Mainers.

I do not criticize the DSA or its allied organizations for advocating against the June Referendum, it was also opposed to their interest. I, myself, was ambivalent on the proposal at the time. But it is now quite difficult to establish the difference between a truly dangerous undermining of rent control – as we are facing this week – and a good faith effort at problem solving, which we voted against in June.

I don’t think Question A will pass this week. But if it does, and Portland’s rent control status quo is plunged even further into dysfunction, we will look back at the multiple opportunities to reach a settlement. Likely with regret.

Vote No on Question A.

Ashley D. Keenan – Ashley is an editor of The Portland Townsman, writer, local small business-owner, and Maine native. Her work primarily covers the mechanics of local government, the ongoing housing crisis, responsible market economics, and New England culture and history. She lives in Portland with her fiancé and can be personally reached at ashley@donnellykeenan.com.

It’s reassuring to see even rent control skeptics see Question A for what it is… A worse deal and a much bigger threat to the community that Question A mark I ever was.

Some questions the analysis raises:

Is it really necisary to increase rent on new construction beyond the allowed amount per year? I don’t know enough about financing to know. It seems like in order to get the funds together to build, the market would already allow a high enough rent to more than break even on financing, even if the market where to stagnate- otherwise you wouldn’t be able to break ground in the first place… Our law doesn’t dictate how much can be charged initially, only how much it can increase each year. How much does new construction’s rent usually go up every year in a normal city without rent control, or in a healthy rental market like Austin TX?

Another which I’ve been thinking about is 3rd point: if we get to the point where the market is stable due to construction of private and public housing and rents aren’t being raised as much as rent control allows them due to market saturation, or they’re even falling as they may have begun to do in Austin TX or Minneapolis, MN, why get rid of it? Not that I think that level of success is likely in Southern Maine…

The threat of falling rents may explain why some landlords are also against zoning reform, and other possible solutions to the housing crisis, come to think of it…