Disclosure: Ashley Keenan lives in a Portland apartment covered by the current rent control ordinance.

Last night, March 20th, the City Council placed a referendum on the June ballot after a bloody session which left neither side satisfied. The citizen’s initiative, sponsored by a local landlord association, collected over 3,000 verified signatures, but accusations rang on for over an hour during a public comment period that many of these were gathered by deceitful petition farmers. Councilor Phillips, recently elected to District 3, attempted to torpedo the referendum with a constitutionally subtle move, and this was supported by a throng of citizens turned out by a social media campaign. It narrowly failed, but the council did opt to edit the title and summary of the referendum, making it less ambiguous (and perhaps less appealing) on the ballot. For all the details and intrigue of this marathon council meeting, see our City Council Review.

What we’re concerned with here is that this June, Portland voters will be asked to vote on a narrow but impactful amendment to Portland’s current rent control ordinance.

That current system, itself, was enacted by referendum in 2020 and amended by referendum this past November 2022. While it’s been around for a couple years now, many residents are still confused by its complex provisions; further misconceptions stem from the fact that it’s somewhat unusual when compared to rent control systems in other cities. In order to make an informed decision this June, one needs to understand what’s being proposed – but also understand the current regime. In the interest of ensuring as great an understanding of the issue as possible, what follows is a detailed explanation of Portland’s rent control as it stands today, as it stands to be amended this summer, and how these sit in context both with our neighboring suburbs and the country as a whole.

Rent control is a uniquely divisive issue, as perhaps no other policy asks so directly “who should we make policy for?” Whether the needs of current residents outweigh potential immigrants, those of families outweigh individuals, those of the elderly outweigh the youth, those of homeowners outweigh renters… these value judgments sit quietly in the background most of the time. But for such a deeply impactful policy as rent control, they necessarily come to the forefront, and with them comes passionate debate. In order to vote responsibly, however, we all must have a grasp of the facts.

Rent Control Today

As stated, Portland’s rent control ordinance (Chapter 6, Article XII) was implemented by referendum in November 2020, and amended by referendum in November 2022 to strengthen its provisions and address loopholes in the original ordinance. In both referenda, the sponsor was the Maine chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA.) Compared to other rent control ordinances in American cities (a more thorough comparison will be made later on) it’s a fairly atypical system, so if you’ve never quite understood it then you’re not alone. Let’s walk through the specifics of the policy to ensure that we know what’s even being amended.

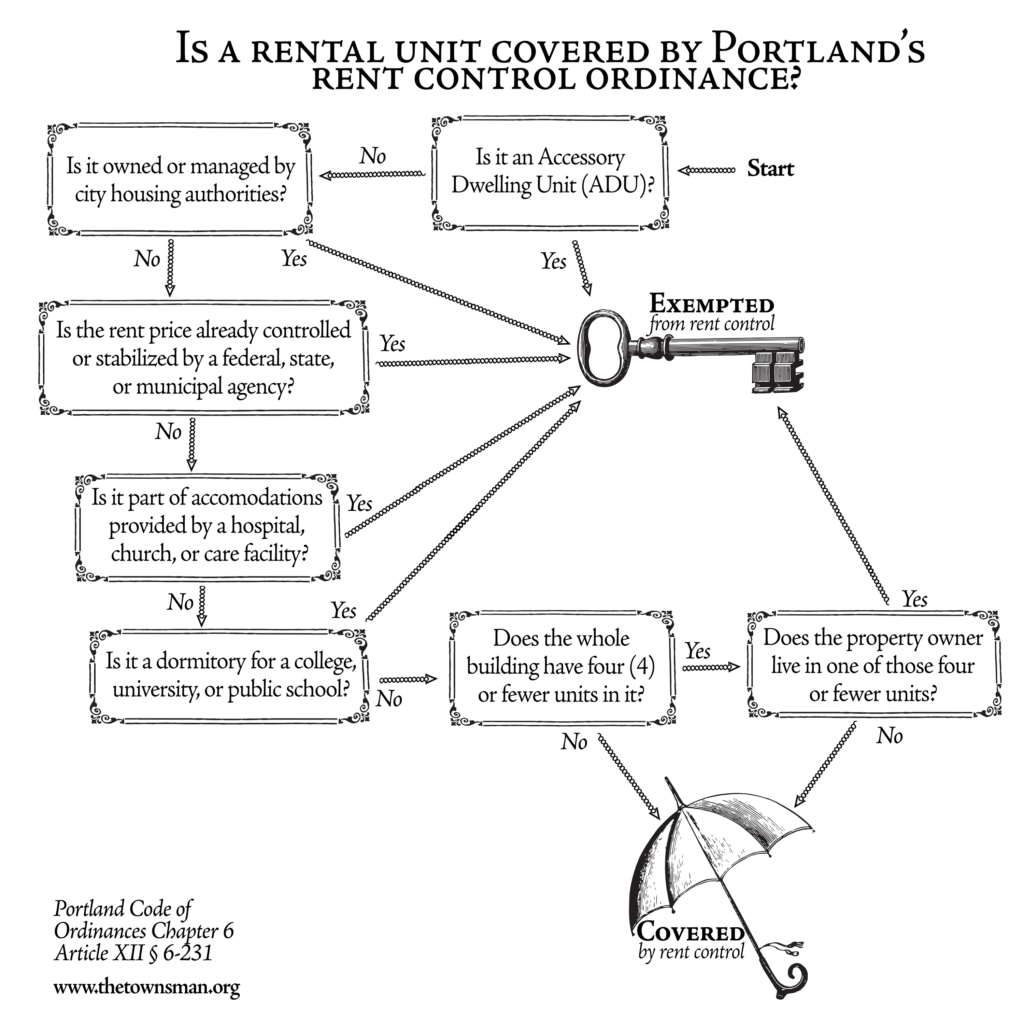

The first thing to understand is which rental units are covered by the policy, and which are exempt.

The rent prices of exempt housing units are entirely unaffected by our rent control ordinance, so we can just put them out of our minds.

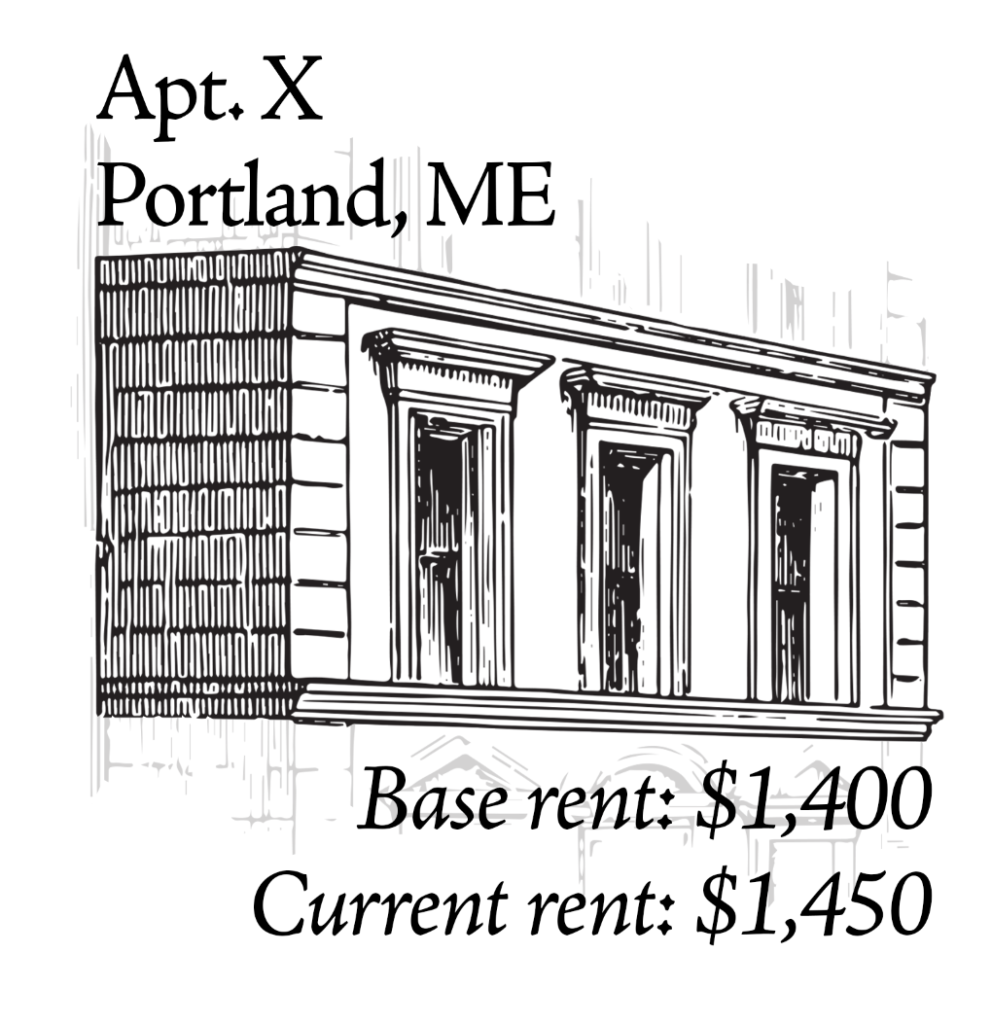

If a unit is ‘covered’ by rent control, it will have two relevant characteristics that are important to understand: its Base Rent and its Current Rent. All covered (i.e. non-exempt) units have both.

• If a unit was on the market in June 1st, 2020, the Base Rent is what the unit’s rent price was on June 1st, 2020.

• If a unit wasn’t yet on the market on June 1st, 2020, the Base Rent is the rent price the unit was first rented for.

• The Current Rent is simply whatever price it is currently being rented for.

Let’s imagine a covered unit, “Apartment X,” which rented for $1,400 per month on June 1st 2020, and was renting for $1,450 in 2022. We’ll use this apartment as our baseline.

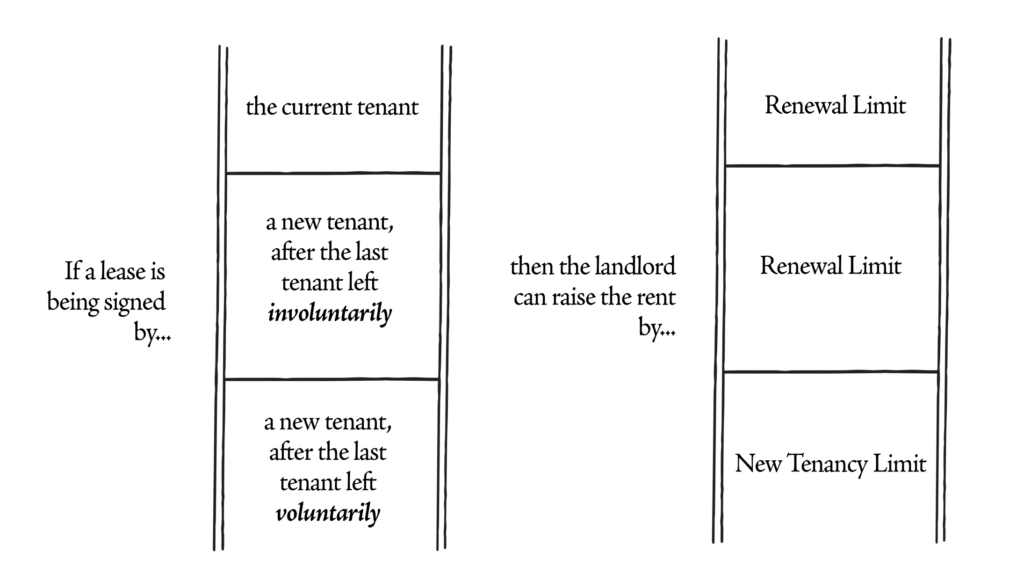

Landlords are allowed to raise the rent on their units once per year, at most, and they are limited in how much they can raise it by. What this limit is depends on the scenario:

As you can see, there are two different limits, a Renewal Limit and a New Tenancy Limit. (N.B. These terms are not used in the code of ordinances, they are colloquialisms.) The first thing to note is that in all cases, whether a lease is being renewed by a current tenant or is vacant and being leased by a new tenant, landlords are restricted in how much they can raise rent. In policy terms this is called “vacancy control,” and can be contrasted against “vacancy decontrol,” which allows landlords to freely set rents to market rate when the unit becomes vacant.

Portland’s ordinance also does not treat all vacancies equally. If a landlord declines to renew a lease with a tenant, or if a landlord evicts a tenant, the vacancy that follows is considered an “involuntary vacancy.” However, if a tenant voluntarily leaves a lease early, or if they are offered to renew the lease but choose not to, the vacancy that follows is a “voluntary vacancy.” In this latter case, landlords have the opportunity to raise rents by a slightly higher limit, as it will not potentially displace the current tenant.

But if a new lease is signed following an involuntary vacancy, e.g. following an eviction, the unit is still bound by the lower Renewal Limit. This is necessary, as otherwise there would be a great incentive for landlords to evict or decline to renew leases.

Calculating the Two Limits

The following examples are for illustrative purposes only, they do not constitute actual estimates of permissible rent increases in Portland for this year or any year.

The Renewal Limit, based on the “Allowable Increase Percentage,” is calculated each year by the Housing Safety Office using the inflation rate (CPI) as measured by the United States Bureau of Labor for the Greater Boston Metropolitan Area. Specifically, the limit shall be set to 70% of the inflation rate for the preceding year, applied to the Base Rent of the unit.

For an example, let’s use the national CPI inflation rate from 2021 to 2022: 8%.

And now let’s go back to our example apartment, which has a Base Rent (its price in June 2020) of $1,400, and a Current Rent of $1,450.

First, we apply the limit rate (70%) to the inflation rate: 70% of 8% is 5.6%.

Then, we apply this new rate to the Base Rent: 5.6% of $1,400 is $78.40

Finally, we apply this dollar figure to the Current Rent: $1,450 + $78.40 = $1,528.40

If you’ve managed to follow this, we can see that the maximum rent a landlord could now ask of their tenant, assuming that they receiving the Renewal Limit, is $1,528.40.

The good people at City Hall don’t actually expect everyone to do this math themselves (they’re not the IRS) so they provide guidelines each year for landlords to comply with. It is worth noting, however, that this binds landlords to raise rents at a lower rate than inflation. This means that every year they are bound by the Renewal Limit, assuming they’re not entitled to other increases, their unit provides less real revenue than the year before.

When a unit has become vacant from the tenant(s) leaving voluntarily, however, the landlord can raise the rent by the New Tenancy Limit, which is the Renewal Limit plus an extra 5% of the Base Rent. For example:

First you calculate the Renewal Limit figure: As already calculated, $78.40

Second, you calculate 5% of the Base Rent: 5% of $1,400 is $70

Then, we add these two together: $78.40 + $70 = $148.40

Finally, we apply this dollar figure to the Current Rent: $1,450 + $148.40 = $1,598.40

So, the new total rent, for a new tenant following a voluntary vacancy, could be as high as $1,598.40, right?

Absolute Maximum Limit

No. There is an absolute maximum limit to annual rent increases set at 10% of Current Rent per year. This means that no matter what additional increases a landlord may be entitled to on top of the Renewal Limit, our $1,450 rent price is absolutely limited to a one year-increase of $145. So, the new rent can be $1,595 or less.

This is the total rent, $1,595, that a landlord could ask of a new tenant, assuming the previous tenant left voluntarily. A common question to arise is “How do we know that a tenant’s departure was actually voluntary?” The rent control ordinance charges the Housing Safety Office with the responsibility to investigate any report it receives that a “voluntary” departure was in fact coerced.

This Absolute Maximum Limit of 10% per year is important to understand when evaluating the proposed amendment on the June ballot, as we shall see. It also means that extra $3.40 can’t be added to the rent.

Banking Raises

But where did that extra $3.40 “go”? When a landlord’s theoretical limit exceeds the absolute 10% maximum, any additional percentage increases are ‘banked.’

There are all sorts of reasons why a landlord might not want to max out their annual increase limit. Maybe they know their tenant is going through a hard time, or maybe they’d rather just use “$1,520” instead of “1,528.40.” Whatever the reason, whenever a landlord chooses not to ‘max out’ their limit, they ‘bank’ whatever increase they chose to forgo. This banked increase can then be applied by the landlord in a later year. This is intended to provide some flexibility for landlords, and to incentivize them to not necessarily max out their rent raises each year. The sum of the Base Rent plus all actual and banked increases is called the Banked Rent, and represents a theoretical maximum rent price.

Banked increases cannot be used to exceed the absolute maximum limit of 10% for annual rent rises. It’s the absolute maximum. With this in mind, a common criticism of Portland’s rent control scheme is that in medium-to-high inflation economies (like we are in now) it is practically inevitable that landlords will accumulate large ‘banks’ of increases that they can never actually ‘spend,’ as they are already hitting the 10% maximum. But even if a landlord hasn’t stored up banked increases, there are other ways to obtained allowed increases.

Additional Raises

An interesting piece of jargon in the rent control ordinance is “fair return on investment.” This is defined in the code as the amount of profit sufficient to allow a “just and reasonable rate of return, to encourage the investment of capital in the rental housing market, to fairly compensate investors for the risks they have assumed, and to achieve minimum constitutionally protected standards.” It goes on further to state that, in typical cases at least, the amount of profit earned by landlords for the 2019 fiscal year should be used as the baseline for a fair return on investment. A system for evaluating the profitability of rental units was introduced by St. Paul in Minnesota based on the principle of “Maintenance of Net Operating Income” (MNOI), a long-standing legal precedent in determining a fair return under rent control ordinances. With this framework, they ask for a substantial amount of data from landlords requesting additional raises, and calculate what to offer them. In 2022, Question C included implementing similar guidelines here in Portland.

Updated 3/21/22 – A previous version of this article misreported the origins of MNOI. Thank you to Buddy Moore for the correction.

Last night, March 20th, rules complying with the MNOI-based ordinance were approved for the Rent Board. Multiple members of the City Council criticized the rules as being too complicated for small-time landlords, requiring full-time accountants and attorneys, but the chair of the Rent Board conveyed that his hands were tied. He agreed that the forms his team produced were very complicated, but that the referendum-enacted statute did not allow for any simplifications to be made.

This Rent Board was also established by the referendum of 2020, and its primary concern is to arbitrate this issue. Landlords who wish to raise rents higher than the limits prescribed in the law have to make their case to this board for why they are justified in doing so. The board is composed of seven members, appointed by the mayor, and while it is not mandatory, the ordinance suggests that they include at least three landlords and three tenants. If the Rent Board sees fit to allow for additional increases, then they can authorize the landlord to do so. Not even the Rent Board, however, can exceed the absolute maximum limit of 10% per year. It’s the absolute maximum.

The Rent Board may also consider adjusting a unit’s Base Rent, a very difficult thing to change under the current ordinance, but only following a “major renovation or reconfiguration” as described in §6-233(c). The only other way for a single unit’s Base Rent to be reset is by taking it off the market for more than five years before leasing it again.

Even with this system in place, and with a competent Rent Board at hand, the idea of a “Fair Return on Investment” still inevitably remains subject to differences of opinion. This is especially the case for the question of “encouraging investment,” which will always be a relative comparison to other towns. For an ordinance drafted by avowed socialists and intended to apply to landlords, we can certainly assume there will be quite distinct conceptions of what a fair return really is.

Other provisions made by the rent control ordinance include a variety of anti-discrimination protections, a complete ban on application fees, and a substantial notification period required for landlords intending to raise rents.

~

This, as it stands, is the structure of Portland’s current rent control ordinance. There is certainly more information contained in the code, regarding edge cases and further specificity, but this basic system is what’s in place right now. How has it affected Portland so far? It’s difficult to say. In the two years its been in effect, COVID-19, a swathe of other housing-related ordinances enacted by referendum, and the recent amendment in November all make it hard to directly tie particular outcomes to particular policies. It will take more time, and more data, to speak confidently. For now, rent prices continue to rise, and housing supply continues down, but it’s really too early to speak conclusively from the data available.

However, this coming June, voters will be asked to choose from two possible futures for Portland.

The June Ballot

Earlier this year, the Rental Housing Alliance of Southern Maine (RHA) began collecting signatures for what they saw as a much-needed adjustment to the current rent control ordinance. The RHA is the organization’s new name, it was founded in 1975 as the “Southern Maine Landlord Association,” and this name (and “SMLA”) are still commonly associated with it. For example, the official website is still www.smlamaine.com. Some have criticized this politically-advantageous shift as being dishonest, but updating a nearly half-century old name isn’t unusual in the world of industry advocacy.

The RHA met and well surpassed the required number of signatures for its petition and submitted its initiative to the city clerk. At this point it was clear that it would be going on the June ballot, and the hearing was set for last night, the 20th of March, to make it official. This is the same routine process that all ballot initiatives go through, and the Townsman prepared to dissect the proposal.

An Intriguing Surprise

But then, just days before the 3/20 council meeting, something unusual happened. Appearing quietly on the agenda, a new attachment showed that two councilors – Phillips and Trevorrow – had sponsored a competing referendum. A rarely-employed tactic explicated (very briefly) in §9-41(c)(3) of the city code, councilors do have the power to sponsor referenda directly, and place them in competition with citizen-sponsored counterparts. A three-way race between the “RHA Amendment,” the “Phillips Amendment,” and the status quo.

In a 3-6 vote, with only Councilor Pelletier joining her colleagues, the council decided against placing this competing referendum on the ballot, but not even opponents of the Phillips Amendment seemed to grasp the subtlety of this move. According to §9-42, and confirmed by city staff in 2021, any new policy enacted by referendum requires a majority… even if it’s a three-way race. This would result in a strongly stacked deck in favor of the status quo, even if only a small minority voted for it.

This is not to say that Councilors Phillips and Trevorrow intended their proposal to be simply a millstone around the RHA’s neck, both testified that their concern was to provide voters with a moderate, via media option, and they are almost certainly telling the truth – but the result of their action would have been to render the RHA amendment probably null and void before the election even happened.

But their proposal failed to garner a majority of the council’s votes, so we don’t need to dwell on counterfactuals (even if they are constitutionally interesting.) This summer, voters will have only two options, to implement the RHA Amendment, or not. So what is it?

The RHA Amendment

This proposed amendment is the first, but likely not the last, attempt to use citizen initiatives to moderate the swathe of laws enacted by other citizen initiatives over the past few years. Despite much concern from tenants’ advocates, this proposal does not seek to massively overhaul the rent control ordinance – indeed the change it proposes is minor, and depending on how it is legally interpreted, maybe even negligible. The full text, unlike so many recent referenda, is very short, so it has been included in full below.

6-233 (c) Base rent upon new tenancy following voluntary termination. If the Tenancy of a Covered Unit is terminated voluntarily by a tenant, the landlord may establish a new Base Rent at their discretion. Voluntary termination occurs when a tenant decides to return the leased premises to the landlord before the expiration of the lease or determines not to renew a lease. The Housing Safety Office shall investigate any report that a tenancy was not terminated voluntarily by the tenant, or that the tenant was coerced or unreasonably influenced by the landlord to terminate the tenancy. Any tenancy in which the property owner served the tenant with a notice to quit or summons and complaint for forcible entry and detainer shall not be deemed to be a situation in which the tenant voluntarily terminated the tenancy.

An Act to Amend Rent Control and Tenant Protections

It also strikes section 6-234(b)(2), which currently governs the new tenancy increase and would be redundant. As an aside, despite the brevity of this proposal, and §9-42’s direction for the city to print the full text of proposed referenda on the ballot, City Council decided to only include the title and summary instead.

This proposal does not affect whatsoever the “Renewal Limit” discussed earlier, which applies to current tenants renewing leases and new leases that follow involuntary vacancies. Instead, it only amends the “New Tenant Limit,” which applies to new leases signed by tenants following a voluntary vacancy. For this, it seems at first glance to switch Portland to “vacancy decontrol,” allowing landlords to set a unit’s new rent price to whatever they choose after a voluntary vacancy. Not only this, but they can also set this new price as a new Base Rent, something which is only possible currently with the express permission of the Rent Board following major renovations. It seems clear that the intent here is for voluntarily vacated units to “break out” to market price.

But does it actually allow this?

Does it Override the Cap?

Despite coverage from major media outlets claiming that this proposal allows for unrestricted rent adjustments upon voluntary vacancy, this may not be the case.

Astute readers will remember the Absolute Maximum Limit in the current rent control ordinance. §6-234(c) reads:

At no time may a Landlord raise the rent of a Covered Unit by more than ten (10) percent. Any rent increases available to a Landlord in excess of ten (10) percent must be banked for later use.

Portland Code of Ordinances, Chapter 6

This categorical restriction doesn’t apply uniquely to the Renewal Limit, or to the New Tenant Limit, but to any and all year-on-year rent increases for covered units. Nothing in the RHA amendment explicitly overrides this. This section is not struck, the section that is struck is irrelevant, and the added text does not provide for a carveout. On a plain reading, landlords are still legally barred from raising the rent on their units by more than 10% of the Current Rent in a 12-month period.

The Portland Townsman spoke with Brit Vitalius, President of the RHA, to ask if this was intentional or an oversight, but he declined to give a statement, merely gesturing that there are multiple possible interpretations. Surely the sponsor of a referendum did not intentionally make it unclear what the referendum actually does. This evident lack of certainty on the part of Vitalius itself may speak volumes. Is it moderation, or a mistake?

By comparison, the Phillips Amendment, drafted in conjunction with the city’s Corporation Counsel, did explicitly override the cap. In §6-234(c), the proposal would have amended the language to read:

At no time may a Landlord raise the rent of a Covered Unit by more than ten (10) percent, except and only as provided in subsection (b)2b in which case a Landlord may not raise the rent of a Covered Unit by more than twenty (20) percent. Any rent increases available to a Landlord in excess of ten (10) percent, or only in the case of subsection (b)2b twenty (20) percent, must be banked for later use.

Proposed Ballot Referendum

Added language in bold. This is what a cap override would probably need to look like, and this is simply not present in the RHA Amendment. Pending further clarification from legal counsel, the current position of the Townsman is that the RHA Amendment most likely does not override the 10% annual maximum.

In any case, far from representing a free-market free-for-all, the RHA amendment may prove to be less impactful for most renters than even the Phillips Amendment would have been. It will almost certainly need to be decided in court what the actual law is, should this amendment pass, but landlords looking to the RHA proposal for salvation may find themselves disappointed.

Base Rent and its Impact

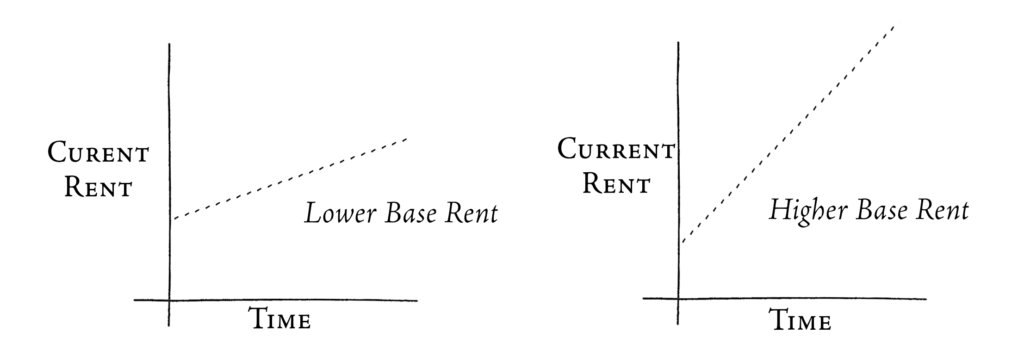

However, the RHA Amendment does still have one unique feature that would be a boon to unhappy proprietors. The ability to not just set Current Rent but Base Rent to a higher figure is a key feature of the proposal. It’s the Base Rent which determines the Renewal Limit, which means that a higher Base Rent results in greater yearly increases being legal.

These will still only kick in after a new tenant moves in, so current tenants need not fear, but this means that units won’t be permanently anchored to their 2019/2020 value, and can instead be periodically adjusted by right. But between those voluntary vacancies, the Renewal Limit will still be linearly calculated, as it is now. A tenant, both now and if the RHA Amendment passes, that sees their rent increase by $100 one year will probably see it increase by about $100 next year too, and the year after that, and so on.

For those that remember Algebra I, the Base Rent determines the slope of the line, but it’s still a straight line either way.

In summary, now that we know all the relevant jargon and assuming that the plain legal reading holds, the RHA Amendment shall allow the following:

After a voluntary vacancy of a unit, upon signing a lease with a new tenant, a landlord can raise the unit’s rent price by up to 10% of Current Rent, and then set this new rent price as the new Base Rent for the unit. (This does not require the use of any “banked increases” or permission from the Rent Board.)

If the legal process finds, instead, that the term “discretion” does override the 10% cap, then instead it will enable (under the same circumstances) landlords to raise the unit’s price to any figure they choose until a new lease is signed, and set that as the Base Rent.

How does this compare with other cities?

A View to South Portland

For an immediate comparison, we don’t have to look far. In the summer of 2022, Redbank Village, a housing development in South Portland with many low-income residents relying on government aid, dramatically increased rent prices for its dozens of tenants. Following a sale of the properties to JRK Investments residents faced unexpected spikes of $400 to $600 extra per month. This shock, which was poised to displace many of Redbank’s tenants, elicited a response from South Portland’s city government, which instituted a ban on evictions and a temporary city-wide ordinance capping rent increases at 10% until a more permanent solution could be found.

Since then, the city has slowly wended towards a permanent rent control ordinance, keeping a leery eye on Portland’s not-always-positive example. Substantially, South Portland approached this goal by council legislation, not dueling referenda, and so has had ample opportunity to tweak, balance, modify, and seek consensus. After many lively meetings during which councilors, city staff, subject-matter experts and residents all gave input, they’ve settled on a final bill that they will be voting on (and likely passing) today, March 21st.

The City Councilors of our neighbor across the Casco Bay Bridge explicitly stated that their intent with their rent control ordinance is to keep long-term residents in their homes, prevent unexpected rent spikes, and ensure that landlords do not exploit their tenants – all while allowing landlords to maintain a degree of freedom over their properties, encourage the building of new housing, and retain harmonious relationships between landlords and tenants.

South Portland’s Policy

The basic structure of SoPo’s pending rent control ordinance is much more straightforward than Portland’s. In brief, Base Rent is freely set by landlords at the beginning of each new tenancy, and every year landlords can raise the rent price by 10% of this Base Rent.

That’s it. Pretty simple, isn’t it? No mention of inflation, Boston, banking increases, a Rent Board, voluntary vacancies, or a “Fair Return on Investment.” But lest you think it’s an unsophisticated policy, it’s worth dwelling on the variety of specific differences between it and Portland’s.

Exemptions

In addition to those kinds of units that Portland exempts, which isn’t very much, South Portland also exempts:

• All new housing.

→ All housing built and first occupied after May 27th, 2023 is completely exempt from this rent control ordinance. This is to not discourage investors from building new housing amid a critical housing shortage.

• Units owned by a landlord who owns 15 or fewer total units.

→While Portland’s policy has little sympathy for “mom and pop” landlords, treating nearly all landlords with the same rules, South Portland explicitly designed this ordinance to only apply to “large” landlords with 16 or more units. There was much debate over where exactly this line should be drawn.

• Short-term rentals

→Portland’s rent control ordinance also applies to short-term rentals, (e.g. AirBNBs) and this has a number of confusing implications. While the language of the law goes a long way to untangling these, South Portland preferred to not deal with them at all.

These exemptions are the most fundamental difference between the two cities’ policies, and is indicative of the responsive nature of South Portland’s interests.

Base Rent

Unlike Portland’s model, which sets a permanent Base Rent tied to a unit’s price in 2020, South Portland sets the Base Rent on a per-tenancy basis, resetting for each new tenant. This provides tenants with protection against unexpected leaps in rent, while also allowing units to reset to market rate on a regular basis.

The Base Rent for each tenancy is set as the initial rent price upon entering into a lease. For current, ongoing leases, it is set to the rent price effective on January 1st, 2023.

Banked Increases

South Portland’s City Council considered implementing a sort of “banked rent” system like Portland, but ultimately decided against it. The reasons for this were various, for one thing councilors were concerned that keeping track of all the banked rents (as Portland’s law obligates our city staff to do) would simply be too much of an administrative burden on South Portland’s small staff.

This does mean, however, that every year’s permitted increase is a “use it or lose it” situation. Landlords have very little incentive to not max-out their full 10% increase every year, since they won’t be able to make up for the difference later (at least until a new tenant moves in.)

Inflation

Very similarly, South Portland also does not consider inflation at all in its limitation, for essentially the same reasons. Portland’s law calls for the Housing Safety Office to use figures from the Department of Labor’s Consumer Price Index for the Greater Boston Area to calculate a unique inflation-tied rate at which landlords can increase their rent each year. South Portlanders think that all sounds way too complicated, “10%” works.

But really, those calculations take expertise and manpower, things that South Portland’s staff don’t have surpluses of (at least according to their own City Council) and so impacted landlords all know that the rate is 10%, every year. While predictable and straightforward, this does mean that in high-inflation environments, landlords may face significantly greater challenges than in low-inflation ones. But perhaps helping tenants during inflationary periods is a good thing in itself.

Voluntary Vacancies

Under Portland’s law, not all vacancies are alike. A vacancy which follows a tenant leaving of their own accord is rewarded with a higher permitted rent increase, while a vacancy in which a landlord evicted a tenant, or declined to renew a tenant’s lease, is more heavily restricted. The intention here is obvious – to discourage evictions and tenancy terminations – but it also punishes landlords for engaging with risky tenants, (e.g. those with criminal backgrounds, or poor credit scores.)

South Portland does away with this distinction, instead treating all vacancies the same, allowing landlords to reset their unit’s Base Rent to market rate. This may encourage more tenancy terminations, but South Portland’s councilors determined this was a remote risk.

Fair Market Rents

One exemption that smacks more of Portland’s intricate rulemaking than South Portland’s minimalism is Sec. 12-505(d). This allows for landlords renting units for below the U.S. Housing and Urban Development Department’s “Fair Market Rent” for South Portland to freely raise the rent to this level. This is to avoid punishing landlords for choosing to rent at below-market prices.

What is the HUD’s “Fair Market Rent”? It’s a figure calculated for every county and a variety of unit types roughly equal to the 40th percentile of rent price. For example, Portland’s 2023 FMR for a one-bedroom apartment is $1,448. Under South Portland’s exception, if a landlord was renting a unit for less than that, then they could freely raise their rent to that figure.

Sunset Clause

The poison is in the dose – this applies as much to rent control as to medicines. Unlike Portland’s ordinance, which actually harshens over time due to its sub-inflationary rate, South Portland has set their rent control law to automatically expire in 2030. The council hopes that by then it will no longer be necessary, but if the council then finds it to still be necessary, then they can choose to renew it with or without amendments.

~

Splintered Twin

South Portland’s pending policy is evidently very different from Portland’s. Some of the distinctions seem clearly superior in one direction or the other, but most are simply differences of philosophy and context. Will one be more successful than the other? We will have to watch things unfold.

But there’s more to the world than just Cumberland County. What other cities have rent control ordinances like Portland’s?

Rent Control Across America

St. Paul, Minnesota

This isn’t the first time St. Paul has made an appearance in our story, and it’s clear we’re walking a similar road to Damascus. Our paths are closely twinned, as we passed our rent control ordinance at the ballot box in November 2020, they passed theirs the same way in November 2021. Both ordinances were expansive in their scope, encompassing nearly all rental units on the market. Both were similarly strict, with ours maintaining a sub-inflationary renewal limit, and theirs ignoring inflation entirely and limiting increases to 3%. Both allow for a similar suite of exceptions, using similar tools to calculate what ought to be a “Fair Rate of Return.” Both, initially, had very similar vacancy control measures, a rare feature in rent control ordinances.

A major difference between our two cities is that St. Paul’s city charter allows for the city council to much more freely amend popular referenda, and the council used this power to moderate some of the strictest provisions in the ordinance, particularly regarding new construction and vacancy decontrol. But despite some accusations to the contrary, the council did not “gut” the ordinance, and it remains substantially in place.

St. Paul is roughly four times the size of Portland, so the impacts were able to be more clearly measured – and many were dismayed by the results. Building permit applications fell by over 80% as, like Portland, new construction was initially not exempt. Since then, more exemptions have been carved out to reverse this cratering of productivity, which has helped to stabilize the situation somewhat. Minnesota too is facing a housing shortage, and this “strictest rent control in the country” did nothing to persuade prospective builders to choose St. Paul. To learn lessons from St. Paul, (as one should,) we may consider implementing our own exemptions for new construction.

San Francisco, California

One of the most famous rent control policies in the country is found in San Francisco, where all units with initial occupancies older than June 13th, 1979 are covered by strict rent control policies. Like in Portland, they have a Rent Board which calculates the permissible rent increase each year. Also like Portland, they have in addition to this an Absolute Maximum Limit, in their case 7%.

Unlike Portland, however, it does not vacancy control, and usually allows landlords to freely set rent to market rate between tenants. In this way, they resemble what Portland would look like if we were to pass the RHA amendment, and it’s found that it does override the absolute maximum limit. Furthermore, San Francisco actually has stricter rules against termination of tenancies, requiring a “just cause” to do so. However, San Fran’s definition of “just cause” includes some questionable examples, including condo conversion.

How has this fairly strict rent control served San Francisco? The city is notoriously unaffordable, with the median rent in 2022 being over $3,300 for an apartment. As in all such warped markets, the answer ultimately lies in supply, and it’s notable that despite only 40+ year old apartments being covered, over 60% of rental units in the city are rent controlled. This points to a sluggish pace of construction, which rent control has certainly been some factor in.

But this should not be taken too far – San Francisco is hardly unique among its neighbors. While SF’s situation is particularly galling, unaffordability and underbuilding is a statewide California problem with state-level factors involved as well. Nevertheless, the hilly city remains a powerful counterexample to the claim that rent control will always bring affordability.

New York, New York

One city that Portland is very much not like is New York City. Certainly the most famous rent control laws in the country, the Big Apple’s headache-inducing patchwork of ordinances with byzantine rules and little consistency is evidence of the policy’s long history. Whereas in most jurisdictions “Rent Control” and “Rent Stabilization” are more or less synonyms, in NYC they reflect two entirely different suites of policy that continue to coexist. In world capital where the median rent is even higher than San Francisco’s, some lucky heirs live in 3-bedroom apartments on the Upper East Side for $1,300 per month. These extremely fortunate renters don’t represent a downtrodden underclass given succor by merciful state intervention, they represent the importance of knowing the right people, and having the right family.

But again, NYC is a very different city to Portland. Unlike Portland’s broadly-applicable, unified, carefully-crafted policy put in place as one whole, NYC’s laws cover a shrinking minority of units as the city tries to move away from its self-diagnosed failures experimenting with the policy. Are there lessons Portland can learn from New York City? I’m not sure there are, actually.

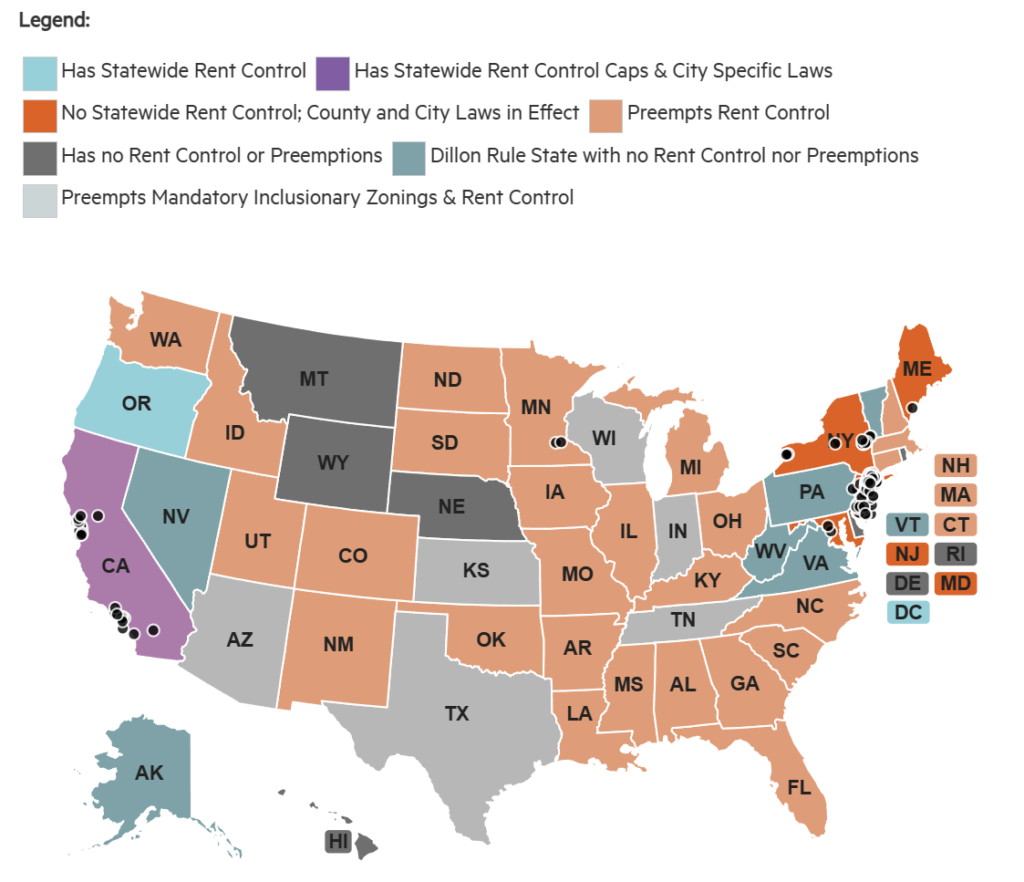

Note the black spots marking cities with local rent control laws.

The Rarity of Municipal Rent Control

If this seems like few examples, this is because local-level rent controls are quite uncommon in America. There are about 200 cities which have rent control, but 162 of these are in New York and New Jersey, and another 18 are in California. The remaining handful of cities are found in the District of Columbia, Maryland, Minnesota and – you guessed it – Maine. And most of those cities, especially in New York and New Jersey, have only quite old rent control laws. Only a handful, including ourselves and St. Paul, are actively expanding new rent control regimes. 44 out of 50 states have no municipal-level rent control at all, and this will necessarily restrict the amount of meaningful data we can gather.

We could look abroad to foreign cities, but comparisons quickly become difficult. Advocates freely point out that cities like Vienna maintain affordability with rent control, but this is only in conjunction with a manic rate of public-private construction unknown in America. Tokyo, an even more affordable city despite its high growth rate, has no rent control, but like Vienna relies on a very high rate of construction to meet demand and keep rents low. We may seek to mimic the policies of Tokyo and Vienna, but for the purposes of useful comparison, we’re mostly limited to the few American examples.

Does this paucity of comparable jurisdictions mean that we should step back from the brink? Or does it mean that we’re leading the pack? Possibly neither, but I think we’d be well-advised to watch our step.

Rent Control According to the Experts

Asking the Economists

It is commonly said that there is economic consensus on the severe negative impacts that rent control has on a city, even among otherwise left-wing academics. Assar Lindbeck, Swedish Economist who once chaired the Nobel prize committee, famously quipped that rent control is “The fastest way to destroy a city, other than bombing.” If this is true, it could render the city’s Sisyphean efforts to implement a strong-yet-balanced rent control policy by referendum over the past years nearly indefensible. But is it so?

A common source for this claim is Econ Journal Watch’s 2009 meta-analysis of economists, which finds across 140 jurisdictions that no notable bloc of economists endorses rent control. In an enclosed 1992 survey, 6.5% of individual economists do record their disagreement with the statement: “A ceiling on rents reduces the quantity and quality of housing available.” But even this tiny minority, EJW finds, does not voice approval for rent control as it exists in most cities which have it.

A more recent survey in 2012 was more specific, asking 42 of the country’s top economists (among a variety of other questions) whether New York City’s and San Francisco’s famous rent controls, and comparable schemes in other cities, have had “a positive impact over the past three decades on the amount and quality of broadly affordable rental housing[.]” Only one, Bengt Holmström of MIT, answered “agree,” and he did so with low confidence (3 out of 10.) No one voted for “strongly agree.” This wasn’t the only issue where the 42 economists reached broad agreement, but it was one of the most one-sided.

Less thoroughly, but more readably, Stanford economist Rebecca Diamond reviewed the available literature for Brookings in 2018, and found that little had changed in the intervening decade. “While rent control appears to help current tenants in the short run, in the long run it decreases affordability, fuels gentrification, and creates negative spillovers on the surrounding neighborhood.” She suggests that related policies, such as a social insurance program to insure renters against unexpected, large rent spikes could be more effective, but that adequate data doesn’t yet exist.

Evidently, among economists, there are fiercely few dissenters against the rent control consensus, and even fewer that are confident in their dissension. Are there any at all? The aforementioned Holmström, despite his response to the survey, hasn’t written anything on the subject. In 1995, economist Richard Arnott wrote a notoriously ambivalent semi-defense of first-generation rent control efforts, but even in this paper he stated: “I shall not dispute that… controls were harmful (they almost certainly were)” The Haas Institute is a specialist team at UC Berkeley funded by the university’s Equity, Inclusion, and Diversity initiative. Miriam Zuk, for the Haas Institute, published a brief blog post in 2015 outlining a potential defense of moderate rent control measures. This hasn’t led yet to any deeper studies.

Our own Maine DSA points to this study from the University of Southern California as evidence for rent control’s positive impacts, but their choice in doing so is questionable. The paper is largely ambivalent, admitting to rent control’s myriad flaws but maintaining that some form of “rent regulation” remains warranted. The policies it does endorse include exemptions for new construction and vacancy decontrol – neither of which are present in Portland’s ordinance, which was written by the DSA. Evidently, they did not base their policy on the findings of this study.

Some lay policy analysts, like Jerusalem Demsas at Vox, accept the detriments, but reason that in unprecedented crises limited rent control protections may be worth it anyway. She does not deny the risks, indeed she characterizes her position as ‘learning to love the bomb,’ agreeing with Lindbeck that the city may be leveled in the process.

Demsas is a journalist, not an economist. Yet, Demsas’ work does point towards the source of rent control’s persistent popularity. Economists, when adjudicating this debate, were concerned with the overall economic prosperity of a city and its immediate environs. Median incomes rising or falling, median costs of living spiking or dropping, quality of life being higher or lower, etc., etc. Taking a snapshot of a city and its residents at a single point in time, and comparing it to other snapshots. If your top priority is the long-term health and prosperity of a city and its long-term residents, then it would be ridiculous to go against the economists.

Qui bono?

But that isn’t how everyone sees the issue. After all, there is the simple fact that for a certain type of person, rent control is almost all upside, at least in the short-term. If you meet the following qualifications, then you are in the ideal position to benefit from rent control:

• You are a tenant in a covered unit

• You can comfortably afford your rent right now

• You plan on staying in the apartment you’re in for the foreseeable future

• You don’t have roommates or other co-lessees

• Your landlord won’t (or feasibly can’t) sell or convert your apartment

There’s a decent chance that these apply to you, and full disclosure: they apply to me. For people like us, the short-term impact of rent control is largely beneficial. We save money. Some others may stand to benefit from long-term rent control, for example:

• Suburban homeowners, who may see significant property value rises

• Landlords of exempted units, who may see significantly higher demand

• Connected people able to acquire leases in low-supply environments

So what sorts of people, according to economists, most suffer under rent control provisions?

• Tenants of non-covered units, who will see greater price rises

• Young families looking to expand their living arrangements, and older families looking to downsize

• Businesses that rely on local workers

• Anyone entering the rental market for the first time, such as immigrants, asylum seekers, young adults moving out of their parents’ home, divorcees, those fleeing domestic abuse, etc.

• Anyone trying to help a friend or family member move to the city, or hoping to move to a new apartment of their own

• Tenants or prospective tenants with criminal records, low credit scores, or poor rental history

In short, anyone that’s already stable benefits, at least in the short-term, while anyone in flux suffers.

The Risks

Of course, most economists would object to my characterization of even those sorts of people as “benefitting,” as the long-term effects impact every resident. Economists have found that in rent-controlled environments, black market mechanisms such as “discrimination, quality deterioration, forced tie-ins, finder’s fees, side payments and bribes” proliferate. We in Maine are often confident that we’re above such things, but the risks of normalizing extra-legal transactions looms over any market. Rent control is also known to decrease the rate of new construction, as Harvard Chair Edward Glaeser observes, comparing build-friendly Chicago to rent-controlled NYC. This is especially perilous for a community like ours in a housing shortage.

But what are the risks of not employing some form of rent control? Well as we saw in South Portland, it is to watch long-time neighbors suddenly and through no fault of their own staring down displacement, and even homelessness. Not only socialists but true conservatives, people who believe in things like continuity of community, find this reprehensible, and we saw how even with the politically divided South Portland council such scenarios can spur united action. Every city that engages with rent regulations has to try and thread a needle between protecting community members from the vagaries of global capitalism while not destroying their own economy. It’s not an easy path to walk.

Looking to June

With all of this context in mind, how ought one to vote this summer? The RHA amendment, it must be said, isn’t unreasonable. It is what its advocates attest it to be: a narrow amendment to the existing rent control ordinance, not a new paradigm overturning it. On the Maine DSA’s webpage opposing the measure, it lists as the top priority for rent control “to keep people housed.” The RHA amendment does not threaten the stabilized rent of current tenants, long-term renters are unlikely to see much either way. Economists nearly universally consider exemptions like the one on this ballot to result in more and higher quality housing compared to vacancy controls, which we have now.

For the specific purpose of keeping people in place, rent control can be effective, notwithstanding economists’ warnings. But a city needs more than to keep people in place. It needs to provide adequate housing for people to move, grow, consolidate, and live freely. Among the crowd of voices sharing their perspective with the City Council last night, one of the most common refrains was how hard it is to find anywhere to live, especially for newcomers. They painted Portland as we’d all like to see it: a safe harbor. Unfortunately, rent control is ill-suited to address this problem. Rent control can help those already set in place, people like me, who are lucky enough to have a comfortable apartment that I’d be happy in for a long time. But for people struggling with too many roommates, or immigrants and asylum seekers, or those fleeing domestic abuse, or those with a criminal record, rent control does little. It encourages people to stay hunkered in place, while discouraging the development of new housing units. It’s an insular policy, but this doesn’t mean it can’t be useful.

Rent control is best at protecting long-term tenants from unexpected rent spikes that would displace them. If you believe that there’s something special about being a Mainer, and that Mainers should be able to stay in Maine, then you may support rent control regardless of your other politics. We saw this happen in South Portland, where even conservatives mobilized to defend long-time residents, and the policy they created has been fine-tuned for that purpose. So how does the RHA amendment affect this intention? As advocates have routinely stated, it is narrowly focused on rent adjustments that follow a voluntary vacancy. Landlords remain incentivized to renew leases and to avoid eviction, as if they pursue such tactics they will continue to have their rent held down. But in the event of a tenant freely choosing to leave an apartment, advocates ask: isn’t freely setting the price for the next tenant a victimless crime?

Critics allege that this will cause rent prices to skyrocket, but high prices are evidence of a simple, heartbreaking fact – too many people want to live in Portland, and we don’t have enough housing for everyone. Some people respond to this dilemma by trying to scare away newcomers, harassing immigrants and criticizing efforts to assist them. A much better solution would be to advocate for plentiful, dense, sustainable housing built by both public- and private-sector hands, overcoming the anti-housing laws put in place to protect suburban aesthetics. A speaker at the meeting last night mournfully relayed that she now lived in Westbrook, as she couldn’t find anywhere to live in Portland. Her vote was stolen from her by housing scarcity.

Rent control is like an opioid. It has a real purpose, and in certain circumstances it’s inhumane to not use it for the relief of intense pain. But it is just a painkiller, not a cure. Using rent control to protect Mainers now while we address our housing shortage may be wise, but if we rely on rent control instead of solving the underlying disease, we will simply waste away.

Only you can decide how you will vote in June, but for the sake of everyone, we must engage with one another as informed stakeholders in our community trying to reach a policy arrangement that we can all live with, in good faith. (Even if they did change their name.)

Ashley D. Keenan – Ashley is an editor of The Portland Townsman, writer on urbanism, local small business-owner, and Maine native. Her work primarily covers the national housing crisis, building sustainable and livable cities, responsible market economics, and New England culture and history. She lives in Portland with her fiancé and can be personally reached at ashley@donnellykeenan.com.

Just want to make a correction here. Maintenance of net operating income (has) been used since the advent if what’s called “soft rent control” or “rent stabilization” in the late 1970’s. It’s not really a debatable piece of terminology. There are years of court precedent establishing it as the legal standard for determining a fair and reasonable return on investment for rent price controls. It was *not* first introduced by St. Paul only a few years ago. Please see the work of Dr. Kenneth Baar.

I disagree with some other subjective statements made in here which are presented as objective fact, namely the speciousness, conflicts of interest, and inherently flawed methodology of Rebecca Diamond’s study, but for now I just wanted to make sure you’re aware that some of your reporting on MNOI is incorrect.

Thank you, I based that origin on comments made by the Rent Board, but evidently there was some inaccuracy with details. I’ve made the correction and cited you. It is the case that the specific guidelines implemented for the Rent Board are based on St. Paul’s implementation, but I clearly mistook the specific for the general. If there’s any further errors of facts you are aware, please let me know!

That’s what stuck out on the first read, besides my policy disagreements. Personally wish you’d stuck with more accepted terminology for certain concepts. Agree with you on vacancy rates being an issue, but might diverge in opinion on the best path forward. I’m very skeptical of the private market’s ability to adequately address this crisis. Think it requires massive public investment. Happy to talk more about this anytime. You have my email.

I guess I’ll also add, as someone who has struggled with substance use disorder, and knows many people whose lives have been destroyed by the opioid epidemic, I found your analogy to be a bit offensive. Housing insecurity, homelessness, displacement, gentrification, addiction — these are all very real issues that affect real people in devastating ways. It seems a bit dehumanizing to reduce this all to a tenuous analogy.

Another incorrect statement here is that only allowing an increase of 70% of CPI doesn’t *necessarily* mean a landlords revenue is decreased, I.e., not providing a fair return. It creates a *presumption* of a fair return that is rebuttable my the landlord.

I will disagree with you here, real revenue axiomatically decreases when rent income rises at sub-inflationary levels. How this is set against costs, profits, re-investment, etc. may vary, you’re right, but real revenue does decrease.

70% is what many cities use. The reason is that at least 30% of the cost of most housing developments are fixed, like the mortgage. In fact, it is generous to assume the costs of maintaining a capital asset are 70% of CPI, since so much of those cost can be capitalized.

Mortgages are not permanently fixed. They have a maturity date, at which time they need to be refinanced. Landlords are highly at risk at these maturities if, like now, interest rates have moved up significantly. The rent control ordinance does nothing to provide relief for such an increase. Even the MNOI adjustment excludes interest expense from consideration.

I think it may be useful to clarify this statement “Exempt housing units are entirely unaffected by our rent control ordinance, so we can just put them out of our minds.”

While its true that the ordinance doesn’t regulate rent for exempt units, a number of important tenant protections were added for those units. For example, banning application fees, limits on security deposits, and non-discrimination based on income source. While the SMLA proposal does not affect those provisions, its not much of a stretch to be concerned about further gutting of the ordinance if SMLA prevails in June.

One aspect of the SMLA initiative itself to be concerned about is the perverse incentive created to create a “voluntary” turnover. How much faith do tenants really want to place in an already overwhelmed City government to ferret out all the sneaky ways landlords will work to get around this? Its hard to see why any tenant would vote yes on this referendum and complicate already difficult tenant-landlord relationships.

That is a good point, and while I was specifically referring to the regulation of rent prices in that sentence, it should have been worded more clearly. This has been edited for clarity, if you’d like for me to thank you in a correction note, just leave your name!

While the level of work behind this is appreciated, and some of the analysis truly helpful, I am sorry the author does not appear to have reached out to anyone in Portland who helped develop, draft, fight for, and pass the two referenda that gave Portland one of the strongest, most effective rent control policies on the eastern seaboard. Every piece was well thought out and modeled after good public policy. Additionally, we could have sent you much more data and resources to bolster the case as to why rent control is helping tenants across the country and in Portland.

That said, there are two publicly available data points which should modify your conclusions that RC is bad for newcomers. The first is housing development post rent control vs prior. The second is the level of rent increase since.

On the first, Portland has approved, on average, 50+ units of housing a month since RC passed. That is compared to <30 units a month in the four years prior. Additionally, almost 1,300 units of housing were under construction in 2022 in the city, the most at any given time in decades. Every economist you cite who says RC slows development should then be questioned.

On the second, the rent board itself, unanimously published a report last year showing that rent increases in the city were below 2% for all units, exempt or not. Compared to the average 8% increases the press herald reported on in 2015 over five years, that is a remarkable turn-around. And while exempt units did see increases higher than controlled units (go figure), the increase for exempt units was only 2.5%.

I hope you will incorporate these statistics into your next analysis, and hopefully come to different conclusion about how rent control hurts new comers to the city. While I agree that it is too early to draw any definitive conclusions, the early data indicates that what the people passed is working as planned. And, at a minimum, showing the naysayers completely off the mark.

Indeed, if anything will hurt newcomers, it not the current law. It is the landlord referenda in June that will allow them to hike the rent and base rent to whatever level they choose.

This is ridiculous. The ” almost 1,300 units of housing were under construction in 2022 in the city, the most at any given time in decades” were all approved prior to RC and the green new deal.

He also sites housing units being approved by Portland, hah. Note that he suggests, but does not say “rental housing units”. These are predominately condos, some of which are renovations of what were formerly apartments.

Bootlickers, rent control keeps broke people in rentals. Disgusting to see all this faux-intellectualism pass as a “newspaper”. YIMBY cultists are a joke. Hard to understand broke people when most of Portland’s residents are now from very well off backgrounds.