Ask any halfway-informed Portland voter to comment on recent elections and you’re bound to hear the term “Referendum.” Technically, what they’re usually referring to is defined in Portland’s laws as an “initiative,” but the term “referendum” has become the preferred colloquialism in this heated debate.

After two years of rising discontent, our City Council is currently deliberating the first major reform to Portland’s referendum process since it was introduced over half a century ago. This past March 27th, the first workshop was held in which the council laid a blueprint for the reforms going forward. This November, as Portlanders are electing a new mayor, they will also be deciding on the future of referenda in our city. While everyone seems to have an opinion on this subject, there are many different ways that the process could be reformed, and few are well-understood.

How did the last two major elections, and this June’s upcoming ballot, come to be so entangled with referenda? How did Portland get here, and what reforms to the law are being considered by the city council now? Is it true that referenda are “taking over” local politics, and that they’re more complex than ever? Or is this just anti-democratic rhetoric? What do other cities do, and what will we be voting on in November?

A reasonable place to start is looking at the law as it exists now. If you feel like you already have a firm grasp of the law as it exists, (and you may not realize all the nuances,) click here to skip to more recent developments.

Referendum Policy Today

You are likely familiar with the general outline of Portland’s referendum process, as prescribed by Chapter 9 of the Portland Code of Ordinances, but it’s worth reviewing the specific provisions to ensure we understand what’s being reformed.

There are actually two kinds of “referendum” that Chapter 9 details, citizen initiatives and “people’s vetoes.” This latter type is used for overturning ordinances voted in by the city council, but is rarely employed, and won’t be reviewed here. For citizen initiatives, as shown in the chart above, the process begins with 10 registered voters forming a petitioners’ committee. This committee presents a petition to the City Clerk, containing their proposal for a citizen initiative, or as we’ll continue to call it, a referendum.

The City Clerk has one week to return the petition to the committee with the appropriate forms, and then it’s off to the races. The committee, and other registered voters that want to help them, have at most eighty days to collect 1,500 signatures from other registered voters in Portland. The signatures must be accompanied by the signer’s printed name, street address, and date of signature. Everyone who takes the time to circulate the petition, (e.g. standing in parks asking passersby for signatures,) must be a registered voter of Portland, and they may charge a fee for their services.

Once a sufficient number of signatures have been gathered, the sponsors of the referendum return to the City Clerk. They file the petition there for the clerk’s office to validate, ensuring that all signatures are legitimate and from registered local voters. This must be done within fifteen days. In order to avoid anxiety during validation, it usually behooves the sponsors of the referendum to gather as many as they can, well above 1,500. For example, this June’s referendum secured over 4,000 signatures, but only 3,087 could be verified by the City Clerk. This is still more than enough, but a ~25% rejection rate isn’t outside the norm.

If the petition is found to be insufficient, the City Clerk returns it to the committee and gives them one chance to fix it. This could be because there weren’t enough signatures, or that too many couldn’t be validated, or some other procedural reason. If this happens, the committee has eight days to register an intent to supplement their petition, and then a further ten days to actually refile the petition. If it is still found insufficient, the Clerk will inform the committee, then keep and seal the package for security.

But if the petition is found to be sufficient, then the City Clerk informs the City Council, and at the next regular meeting of the City Council they will set a date for a hearing. This hearing must be within the following 30 days. At this hearing, the City Council can’t just reject the proposed referendum, but it does have a few options:

- 1 ~ Approve referendum for ballot. This is the most common and straightforward response, being used for all twelve referenda over the past two-and-a-half years. Simply put, the council approves the form of the question, and directs city staff to put it on the ballots for the next regular election. This election must be more than 60 days away, but not more than 180 days away. If there is no regular election scheduled that fits these criteria, then a special election is called.

- 2 ~ Adopt a competing measure, then approve for ballot. This subtle prerogative held by the council was attempted (unsuccessfully) this past month by Councilors Phillips and Trevorrow for this June’s RHA referendum. This option allows the council to sponsor its own version of the citizen-initiated referendum, (typically a more moderate version,) to go on the ballot alongside it. This turns a simple yes/no vote into a three-way race, but the consequences are even more profound, as city law requires a majority vote to implement an ordinance by referendum. This means that either the citizen or the councilor referendum needs to get more than 50% of the vote, (a difficult feat in a three-way race,) otherwise the status quo will prevail. This can torpedo an otherwise-promising campaign, and is the closest thing the council has to killing a referendum. After this is approved, the actual citizen referendum is approved for the ballot in the same way as the first option.

- 3 ~ Adopt the referendum. This last option is the most drastic, and was recently attempted (unsuccessfully) by Councilor Zarro regarding Question E in the November 2022 election. In this case, the council votes to adopt the proposed ordinance immediately, bypassing the need for the referendum entirely. While this might be done by a friendly council, it may also be done by a council hostile to the referendum, as (among other reasons) it does not carry with it a 5-year limitation on amendment. This limit will be discussed more later, and the adopt-and-amend process was detailed on the Townsman in more depth here.

Excluding that third option, no matter what happens, at the end of this hearing, the referendum goes on the ballot. While these hearings often bring out supporters and opponents of the referendum to give public comment, as if to sway the City Council, the council is actually quite limited in what they can do. One of the few things they can do is decide how they direct city staff to present the referendum to voters.

The code calls for the full title and text of the proposed ordinance contained within the referendum to be printed on the ballot, but at the council’s discretion, the city may opt to print only the sponsor-provided summary instead of the full text. This option has been consistently utilized by our City Council in recent years as a cost-saving measure. If the council does choose to only put the title and summary of the referendum on the ballot, (both of which were supplied by the committee sponsoring the referendum,) they may also choose to edit the title and summary to more accurately, fairly, or neutrally portray the proposal. This happened last month when Councilor Dion led the effort to slightly reword the (as it was perceived) misleading title and summary of the RHA’s referendum.

At this point all relevant parties probably busy themselves preparing for the vote and campaigning for their preferred outcome. Procedurally, there’s nothing further until election day.

On election day, the voters cast their ballots. If the referendum fails, then it obviously does not come into effect. There is nothing preventing sponsors from trying again with substantially the same referendum next election, though this hasn’t happened yet.

If the referendum earns more than 50% of the vote – not simply the most votes – then it passes, and comes into effect 30 days afterwards. No further action on the part of the council is necessary, this entering into law is automatic.

And finally, here is the element which has garnered perhaps the most criticism out of any part of the referendum process: this ordinance may not be amended by the City Council for five years. This is a very long time in politics; a City Councilor term is only three years. The referendum can be amended by a new referendum, indeed this was done in 2022 when the DSA-sponsored Question C amended the ordinance passed in 2020 by the DSA-sponsored Question D. (Incidentally, in doing this, the clock was essentially “reset” to a fresh five years.) But the city’s elected officials will have their hands tied from making even slight amendments to the ordinances exactly as passed by referendum.

That’s the referendum process as it exists in Portland, and it is the same as it has been since 1991, (the last notable amendment,) and substantially the same since 1954, (when it was first introduced.) The Interim (and candidate) City Manager has called for this system to be “brought into this century.” But for a policy that’s been in place for so long, it seems like we’re hearing about it a lot more now. Why is this?

Referenda over the Past Decade

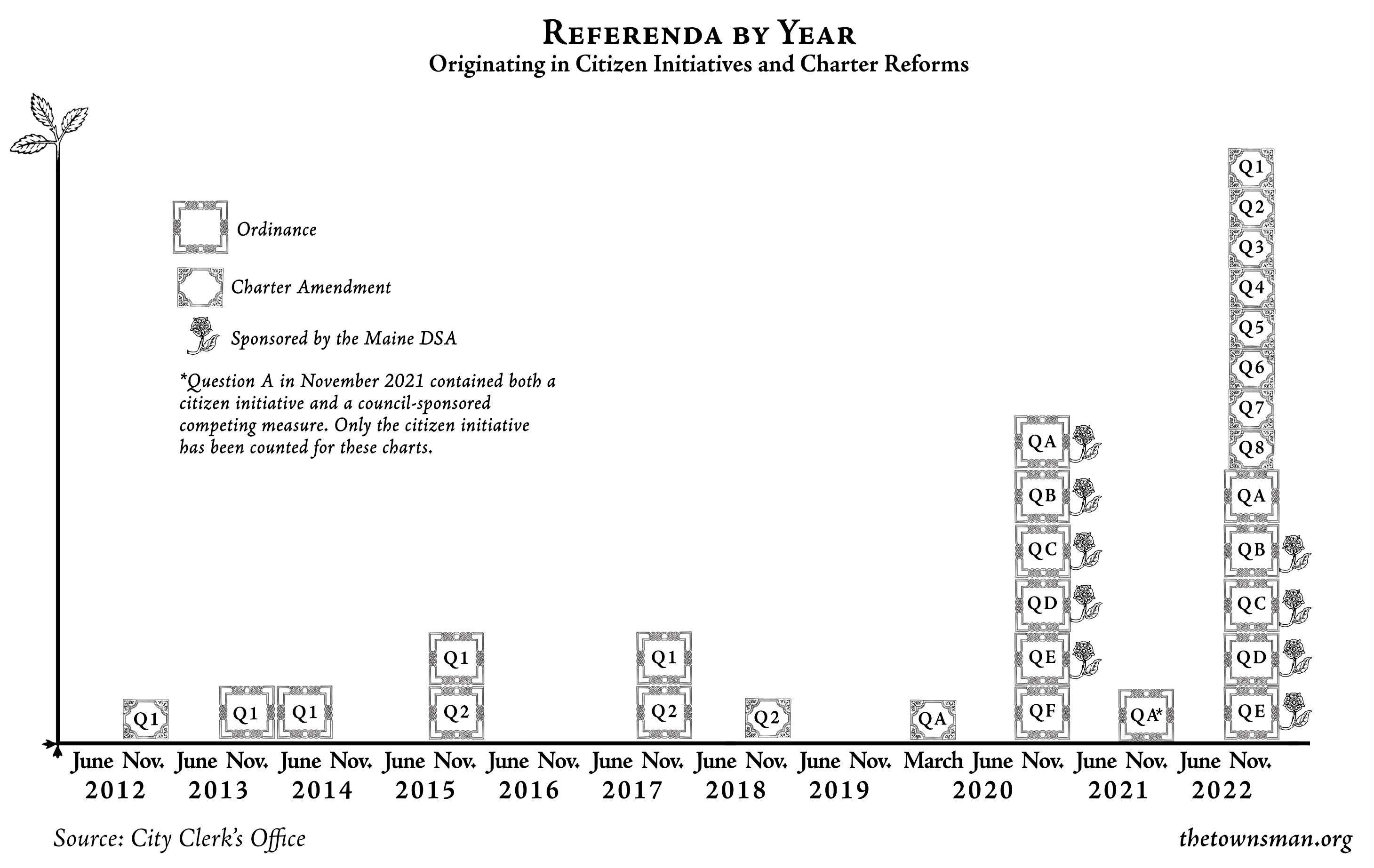

It is often said, in one form or another, that the past couple of years has seen unprecedented exploitation of this process to pass sweeping legislation without legislative review. Is this true? To zero-in on a particular word there, “unprecedented,” we can ask: what does the recent history of citizen initiatives look like?

In terms of count, it’s evidently true. At no time in the past decade, prior to 2020, were more than two citizen initiatives on a single ballot. But 2020 saw six of these referenda, and 2022 saw five more. 2022 felt even more overwhelming because on top of these five initiatives there were also eight proposed charter amendments, (something dedicated readers of the Townsman will remember.)

A single organization, the Maine chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America, has single-handedly driven this explosion in referendum use. In the above chart, referenda sponsored by the Maine DSA have been marked with a rose, (a long-time symbol of democratic socialism,) and of the twelve citizen initiatives proposed since 2020, nine have been DSA-sponsored. And one of the remaining three was proposed as a direct challenge to a DSA proposal.

Of the nine they’ve sponsored, five received approval by a majority of Portland voters and passed into law. The DSA is without question one of the most active, dedicated, and – by virtue of their own industry – influential political groups in Portland. With the ongoing cost of living crisis, change is obviously needed, and the Maine DSA are proud of using all legal options available to them to implement reforms they believe to be desirable.

Significant criticism has been weighed against legislating this way, however. Ordinances which originate in City Council usually start with the initiative of a popularly-elected politician in a committee setting, where they can receive input from city staff, subject-matter experts, and the general public. It is then voted on by the committee before going to the City Council, which over the course of two meetings reads, debates, amends, and votes on the law out in the open, and after public comments. Meanwhile, referenda are written by private, unelected individuals or groups behind closed doors, with no requirement for public or expert input, before being put directly to the voters without any changes.

The Maine DSA has scrupulously adhered to the law, there is no question of impropriety as concerns their sponsored referenda. Despite this, many Portlanders have felt as though their actions constitute a breach of norms, if not law. As we can see, despite it being fully legal, the average rate from 2012-2020 was less than one referendum per year. But the accusation of breaking norms goes beyond the number of referenda, it also concerns the character of the ordinances proposed. The accusation goes like this, “Not only are there more referenda, but they’re much bigger and more complex than before!”

Complexity

Is this true? How does one measure complexity? There’s no objective way to measure the ‘complexity’ of a law, but we can try to sus out an outline by using some abstraction which is more easily graphed: word count.

This isn’t a perfect strategy, but with the enormous help of Paul Riley at the City Clerk’s office, I was able to analyze the full text of every ordinance proposed by referendum since 2012. Not the summary language, which is often printed on the ballot, but the actual changes to the Portland code of ordinances. By putting together the text added by the proposed ordinances with the text struck from the existing code, we arrive at a figure that can be said to estimate the breadth of the impact an ordinance had (or would have had) on the code.

Even assuming perfect data, a longer sentence is not necessarily more complex than a shorter one. But laws aren’t literature, and in calculating these figures, I feel confident that these at least loosely correspond with the legal complexity of the ordinances. The charter amendments have been left out, as they are largely not comparable to ordinance proposals. Some of the documents provided to me, unfortunately, were low-resolution scans marred by watermarks that couldn’t be counted with digital tools, so I had to do it by hand, and as a result single-digit errors are likely.

Full methodology and collected data can be found here.

What can we conclude from this data? Clearly 2020 remains an extraordinary year. The total word count for the six referenda that year are more than double the previous high in 2017 (5,649 words.) And it must be said that in 2017, Q1 failed, while questions A, B, C, D, and F in 2020 all passed into law. We can also see that in 2020, the one non-DSA referendum, QF, is the shortest of the proposals (555 words.) We can see a similar pattern in 2022, where the only non-DSA referendum, QA, is the shortest at just 333 words. (Look at those angel numbers.)

It must be said, however, that 2022 looks more like a reversion to the mean here than in the previous graph. While there were five citizen initiatives, only one (QC) compares to the behemoths of 2020. Of course, QC was also the only one to be approved by voters. Looking at the word counts, 2022 looks less like continuing an exponential explosion and more like a cooling-off period.

Even so, the burst of complexity and almost-universal success of 2020’s referenda have offended many voters, who feel as though laws of this size and nature need to undergo careful review and deliberation in a legislative setting in order to avoid unintended consequences.

Since 2020, there have been recurring calls to make amendments to the referendum process. In the wake of 2022’s election, the Townsman joined them. The time seems ripe for reform. Since most referenda this past November failed, change now will be less likely to be interpreted as going against the will of voters compared to if they had succeeded. Mayor Snyder, who is leading the charge on reform, is not running for reelection, and so may feel more free to approach a controversial subject like Chapter 9. June’s RHA referendum shows that it’s not just the left that can try to pass legislation at the ballot box. And finally, by buttoning up reform in 2023, the playing field will be well-understood for the big election year in 2024. So what’s happening?

Referendum Reform in 2023

The story actually starts in December 2022 when in a goal-setting meeting with City Council, Mayor Snyder broached the topic of Chapter 9 reform. As the council did not take it up as a formal ‘goal,’ it was moved to the backburner for a time. As February rolled around, however, councilors began to take greater interest in the topic, (possibly due to the rising profile of the RHA referendum aimed at the June ballot,) and a workshop was scheduled for March 27th. Portland’s Acting Corporation Counsel, attorney Michael Goldman, began to sketch out formulas for reform based on the suggestions of the Mayor and Councilors.

Meanwhile, the RHA referendum had secured sufficient signatures to be placed on the June ballot, and as our own Erica Snyder-Drummond painstakingly covered in the March 20th edition of City Council Review, this referendum to moderate the DSA-sponsored rent control referendum brought out dozens of furious public commenters and threw the council into an hours-long debate over how to respond. While ultimately the referendum did get placed on the ballot with only minor tweaks to its summary language, multiple members of City Council that night reaffirmed the urgent need for referendum reform.

Next week, the 27th, the first workshop was held, and from the activity that night we can make out what the proposed changes will look probably like. Please note that the following observations are based on our impressions from the discussions held, and may not perfectly reflect the inner beliefs of councilors.

City Council Workshop on March 27th

Following first a special meeting where the city manager relayed that nearly a thousand asylum seekers had arrived in Portland since January 1st, and another workshop regarding the forthcoming public campaign fund, the City Councilors set to work to discuss how they wanted to amend Chapter 9. Corporation Counsel led the first part of the meeting, starting with how Chapter 9 actually can be amended.

Chapter 9 itself is the only part of the code of ordinances which can’t be amended by citizen initiative. It has to come from the City Council and be confirmed at the ballot box by referendum (according to the current legal understanding of city staff.) So when might this public vote be held?

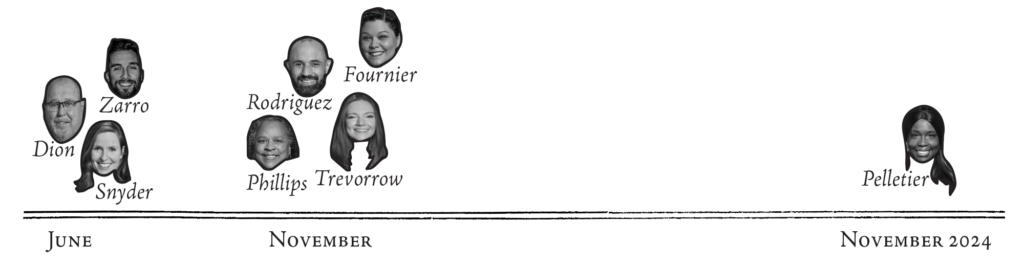

Timeline of Reform

Mayor Snyder, who had initiated the reform process back in December 2022, informed the council that if they could reach consensus, they still had ample time to place a reform package on the June ballot for voters to approve or reject. If the rules could be settled in the summer election, that would mean any November referenda could be aware of the new situation. Councilors Ali, Dion, and Zarro all voiced support for this idea from Mayor Snyder.

However, Councilors Trevorrow, Phillips, Fournier, and Rodriguez expressed that November 2023 would be the ideal time to hold the reform vote, rather than June. Each argued that a November ballot would be fairer and more representative, but perhaps Councilor Rodriguez captured the mood of the room best by stating simply: “It’s an aesthetic thing. It just looks better.”

Standing alone, Councilor Pelletier suggested waiting until November 2024 – a presidential election year sure to have a high turnout – to have the people vote on reform. She believed this period of nearly two years would allow for adequate community input.

Ultimately, a consensus around November formed. Portland voters can expect to vote on the council’s reform package then.

Signature Requirements

The first substantive issue to be debated was over whether or not the number of signatures required by initiative committees should be raised. As discussed in our previous article, Portland is fairly unusual for requiring a fixed number of signatures (1,500) as opposed to some percentage figure proportional to the electorate. 1,500, compared to our population of nearly 70,000, is also on the lower side of comparable cities. There are some cities with lower requirements, but our neighbor to the north Bangor requires a whopping 20% of active voters to sign a qualified petition.

If nothing else, the expectation from city staff seemed to be that Portland should follow national trends and implement a proportional, rather than a flat requirement. X% of voters, rather than a simple number.

Mayor Snyder, as well as Councilors Phillips, Zarro, and Dion all voiced support for raising the minimum. Phillips, while wanting to keep the number accessible, stated flatly that “1,500 is way too low.” However, Councilors Trevorrow, Fournier, and Pelletier all fired back that raising the signature requirement would be an anti-democratic change, and the ballot box should remain open. Councilor Pelletier in particular cited New England’s traditions of town meeting government and direct democracy in her defense of 1,500.

“1,500 is way too low.”

Councilor Phillips

Again, however, Councilor Rodriguez managed to capture an underlying feeling. He reminded the rest of the council that the organizations involved with collecting signatures, notably the controversial DSA and RHA, were more than capable of raising 5,000 signatures for their referenda if they had to. Whether or not to raise the signature requirement, therefore, was of less importance than the reforming the nature of referenda once they’ve passed.

No consensus was reached on this topic, though some change seems likely.

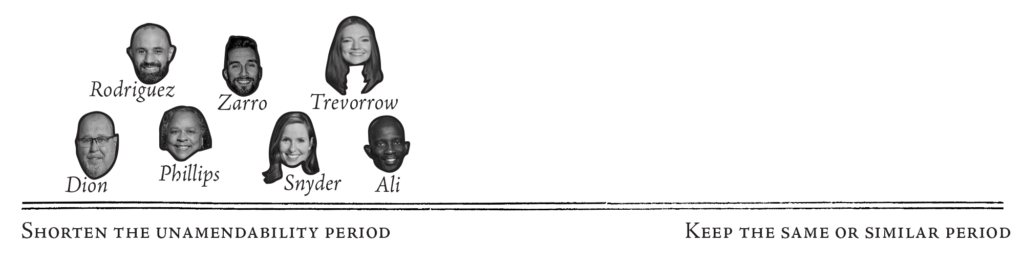

Amendability – Length and Strength

There was virtual unanimity that the current provision in Chapter 9, which bans all amendment to referendum-enacted ordinances for five years, had to change. But how? There are two major elements that the councilors discussed, shortening and softening.

Shortening is precisely what it sounds like, taking the five-year period and reducing it to some shorter length of time – even zero. There was no dissenting from the position that the five years is simply too long.

Councilors quickly brought up the idea of softening the period as well. This would mean that, even within a shorter period of unamendability, there would still be some mechanism for amending the ordinances passed by referendum, with some restrictions.

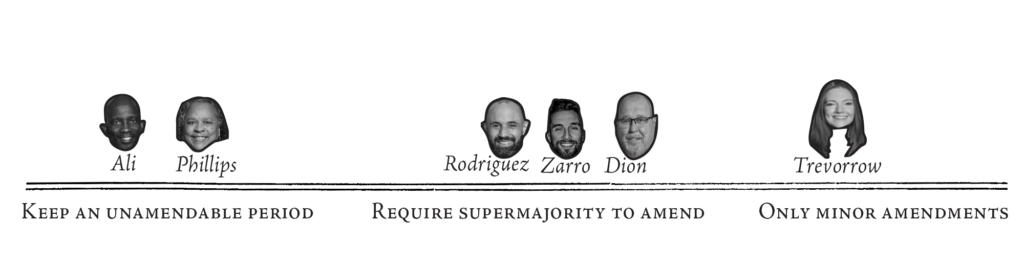

Councilor Rodriguez proposed that amending an ordinance passed by referendum should be possible but require a supermajority. Instead of needing a simple five-vote majority, the council would need seven votes to amend. Councilors Zarro and Dion supported this idea, citing the importance of a united City Council being able to respond to unforeseen circumstances.

Councilor Trevorrow agreed that some sort of softening was necessary, but instead of requiring a supermajority, her position was that the City Council should be limited to tweaking, not overhauling, any referendum. There should be a period where the council can make minor amendments, changing particular figures or provisions while maintaining the overall intent of the ordinance, with simple majority votes. This was a nuanced middle-ground, but other councilors were concerned that what defines a “minor” amendment, or what the “intent” of a referendum was, would all be very complex and subject to controversy and lawsuits.

Finally, Councilors Phillips and Ali both stated that while the period should be shortened, there shouldn’t be any softening at all. A two-year period, perhaps, where the ordinance remains unaltered would give the law a chance to succeed or fail on its own terms. And once that period elapses, then the council will be able to do whatever it wants with the law.

While there was consensus that the five-year period must be abolished, no specific provision reached consensus. Corporation Counsel was directed to explore the legal possibilities for these ‘softening’ measures.

Fiscal Impact Statement

By the council’s Rules of Procedure, any proposed ordinance that a councilor brings forward that would have a financial impact of $50,000 or more per year must include a “Fiscal Impact Statement.” This statement must describe in detail the projected costs, revenues, savings, and any effects on the tax base that an ordinance would entail. This detailed statement is required because, the thinking goes, such information is necessary for councilors to make a rational decision.

For example, if a City Councilor wants to enact some new program which would require a new full-time staff member – whose annual salary would be projected at ~$55,000 – then a Fiscal Impact Statement would be required.

Referenda aren’t bound by this rule. Citizens can propose ordinances without preparing these statements. A natural justification would be that unlike City Councilors, who have access to full-time city staff members who can assist in preparing these figures, normal citizens can’t easily create such statements.

However, though in years past this might not have mattered, things have changed. While the referenda sponsors don’t have to prepare statements, in 2022 the city did assess the fiscal impacts that the proposed referenda would entail. Below are the estimated annual costs (including losses in revenue) for the questions:

Question A, sponsored by the Committee to Keep Portland Local – $175,000

Question B, sponsored by the Maine DSA – $127,500

Question C, sponsored by the Maine DSA – $175,000

Question D, sponsored by the Maine DSA – $2,100,000 (plus school budget costs)

Question E, sponsored by the Maine DSA – $3,000,000

Of these, only Question C passed, but considering the sizeable price tags that some of these referenda carried, to some it seems only fair that sponsors of such questions should have to prepare these fiscal statements themselves.

Among those was Mayor Snyder, who brought forward the notion of requiring citizen committees to create Fiscal Impact Statements when they turn in their 1,500 signatures. These could perhaps even be put on the ballot for voters to review alongside the text (or summary) of the ordinance.

Among the muted approval, Councilor Trevorrow dissented, stating that voters should decide whether to vote for or against a referendum on the “merits of the issue.” She went on: “[A] Fiscal Statement influences the vote outside the merit of the issue.” The notion that what an ordinance costs is independent of its “merits” is certainly one conception of the meaning of that term.

Again, no consensus was reached on this item.

Publication Costs

The City Clerk was given the chance to explain this little-explored issue of publication costs. Under the current law, the city is obligated to print the full text of referenda in the Portland Press Herald twice prior to the election. In 2022, this cost $32,000.

The fact that the city was forced to pay this much money (to a private company) to print the text in a physical newspaper (that costs the reader money to purchase) received nearly universal criticism from councilors. Councilor Trevorrow called the requirement “totally antiquated,” and other councilors brought up the idea of moving to an online publication instead, or some cheaper form of print publication (possibly with a free paper.) These ideas garnered general approval.

Only Councilor Phillips stood strongly against the idea, as she said that she valued printing the full text twice in the Press Herald, as “there’s a lot of people that don’t have the internet.”

A consensus emerged that some cheaper option must be found, but no specifics were settled on.

Per-District Requirements

An idea from Councilor Zarro, representing the off-peninsula District 4, was to take district representation into account. Instead of requiring a simple 1,500 signatures from anywhere in the city, a committee could instead be asked to collect (say) 300 signatures from voters in each of the city’s five districts. This would ensure that the densely-populated and politically distinct districts 1 and 2 couldn’t ignore the interests of the off-peninsula districts. Ideally, this would minimize the amount of interdistrict hostility, with outer residents feeling more represented on the ballot. This would guarantee a certain “lens of equity,” according to Zarro.

However, this was an unpopular idea. Councilor Rodriguez (At-Large) rejected the idea that this per-district requirement would be more equitable than the status quo. Councilor Dion (District 5) concurred in this rejection, despite his own constituents standing to benefit. Councilor Trevorrow (District 1) also naturally disagreed, and compared the proposal to the electoral college in favoring less-dense areas.

Councilor Zarro didn’t strongly defend his idea, and seemed content to let it fall out of consideration.

Paid Signature Collection

A controversy which marred the progress of this June’s RHA referendum was the question of paid signature collectors. While many of the RHA petition’s signatures were collected by genuine volunteers, some petition circulators were compensated for their work. The controversy arose from many who affixed their signatures claiming they had been misled by these paid collectors, who misrepresented what the petition was actually for. As far as is known, no laws were broken in this process, but many nonetheless felt that this was a bad-faith practice.

Naturally, then, the idea of banning paid signature collection came up at this workshop. Councilor Zarro was strongly in favor of this ban, stating that this would restore legitimacy to the process. Councilor Ali took the opposite position, strenuously opposing the idea of a ban as an unnecessary infringement on the flexibility of political organizations.

This led to the question of whether, legally, this was even permissible. Corporation Counsel wasn’t sure, and this is one of many things that he is expected to research and weigh in on at the next workshop. As there is such a heavy legal question mark, no consensus formed.

November-Only Referenda

The RHA referendum on this June’s ballot also inspired criticism for its timing. June elections usually have a lower turnout than November elections, so it may be possible for less-popular ordinances to be passed by referendum in the summer. While there’s nothing inherently undemocratic about June elections, many anti-RHA voices seemed to assert that a June referendum is less legitimate than a November one.

In response to this, Councilor Trevorrow proposed that referenda should only be voted on in November elections. Councilors Rodriguez, Zarro, and Dion all expressed some friendliness to the idea, but a strong consensus was not reached.

Single-Subject Rules

This last reform was not discussed on the 27th, but we have reason to believe it will be discussed at the next workshop on the subject. Many states and cities that allow for citizen initiatives, especially in the Midwest, have them abide by a single-subject rule. This is exactly what it sounds like, every referendum may concern only one issue of law.

For example, this past November’s Question D was widely known as the referendum for raising the minimum wage. But in fact, it proposed three separate, significant reforms:

- Raising the minimum wage

- Eliminating the tipped wage

- Establishing a city labor department

If Portland had a single-subject rule, the City Clerk (or some other authority) could have the sponsor of the question divide their proposal into three separate referenda. This would put an end to the sprawling, complex packages of ordinances such as the “Green New Deal” passed in 2020 which, under a single-subject rule, would have had to be 5-7 separate questions to have the same effect.

“Damned if you do, damned if you don’t.”

Mayor Snyder

Looking to November

While not every issue reached consensus, this workshop was a fairly productive one. It gives us a very strong idea of what the future of referendum reform will look like. First, the election on this will almost certainly be held this November, 2023. While some voices preferred June, and one preferred November 2024, the current trajectory is aimed for November.

What reforms will be in this proposed package? We can sort these into categories of probability:

Reforms VERY LIKELY to be on the ballot:

- A shorter period of unamendability than the current five (5) years

- A less expensive method of publicizing referenda than printing the full texts twice in the newspaper

Reforms LIKELY to be on the ballot:

- A ‘softening’ of unamendability, perhaps requiring a supermajority, or fidelity to ‘intent’

- A higher signature requirement for referendum petitions

- Having referendum ballots only in November, not June or other dates

- Mandating referendum sponsors to publish Fiscal Impact Statements with their proposal

Reforms which MIGHT be on the ballot:

- A ban on paid signature collectors

- A single-subject rule

Reforms which will LIKELY NOT be on the ballot:

- A per-district requirement for petitions

These predictions should not be taken as scripture, but from the current positions of City Councilors, we can see where things are headed. If you have any thoughts on these reforms, or if you’d like to propose one that the council hasn’t yet considered, you should reach out to your councilor ahead of their next Chapter 9 workshop on May 8th, (if they do not schedule one earlier.)

Even though the popular vote won’t be until November, according to Mayor Snyder, the council will likely vote on their final reform package by the end of summer. So don’t wait too long to reach out to your representative! After that, the public will have several months to ruminate on the reform package proposed by the council and decide how to vote.

Striking a balance between the weights of council-passed and referendum-passed ordinances is the purest distillation of the tension between Republicanism and Democracy, and it is here, at the local level, that these differences matter the most. Deliberation, expertise, and proceduralism poised against private initiative, populism, and swift action. This will be an enormously important vote, setting the stage for the next decade of Portland’s mode of governance. If significant reforms are not made, we will likely enter a period of “Referendum Pendulum” government. We are already starting to see it, with the RHA referendum this June being an amendment to the DSA referendum which itself was an amendment to an original DSA referendum. Is this how we want to be governed?

Ashley D. Keenan – Ashley is an editor of The Portland Townsman, writer on urbanism, local small business-owner, and Maine native. Her work primarily covers the national housing crisis, building sustainable and livable cities, responsible market economics, and New England culture and history. She lives in Portland with her fiancé and can be personally reached at ashley@donnellykeenan.com.

You state that “questions A, B, C, and F in 2020 all passed into law.” Question D, regarding implementing rent control, also passed in 2020.

Thank you Damon, that was a typo. That’s been fixed!