This is Part 2 in a three-part series on Franklin Street published by the Portland Townsman. See Part 1 here.

In the first part of this series on Franklin Street, its history and its future, we surveyed how a city street was transformed into an urban highway slicing through the middle of the peninsula – and scattering communities in the process. The problems that we’ve inherited in this street are well-known, and hardly unique to Portland; 20th century urban renewal projects subjected many cities to similar troubles. Solutions enjoy less consensus. Since the neighborhood rebellion against the 2006 plan to further entrench the road’s inadequacies, Portlanders have been engaged in a serpentine process to fix this road. What’s been done, and who has done it? Is there a single clear future for Franklin, or are competing visions still fighting for it? How much will it cost, and who will bear the burden? Will we ever actually pull it off?

This author has been at the heart of this matter for nearly two decades, and the path hasn’t been straightforward. Those who want to understand the current debate over Franklin Street must understand the political struggles and progress which have led to today.

Making the Plan

Lead by neighborhood organizations, the Portland community had soundly rejected the road-widening schemes of the 2006 Peninsula Traffic Plan. There was a dawning sense that new approaches were needed to achieve different outcomes. In 2007, community leaders from the Bayside and Munjoy Hill neighborhood organizations, under the auspices of the Franklin Reclamation Authority (a coalition of concerned citizens, not a governmental organization) organized a community workshop to chart a different course in the search for solutions to Franklin Street. The outcomes of the workshop, presented in a report titled “Revisioning Workshop for Franklin Arterial” included a description of the problems with Franklin Street, but also articulated a vision of the street as a vibrant integral part of the Portland landscape.

The group shared this work with City Manager Joe Gray, who was impressed enough that he secured a small budget to explore alternative ideas for Franklin Street. This study, “Reclaiming Franklin Street,” began in early 2008 and included representatives from the Maine Department of Transportation (MaineDOT), the Federal Highway Administration (Franklin Street, as a primary arterial, is considered part of the federal highway system,) the local transportation planning agency PACTS, and a public advisory committee (PAC); this PAC in turn represented local residents, business organizations, and out-of-town commuters, among others who had a stake in the local transportation system. The PAC was chaired by Boyd Marley, who had just completed his final term as a state representative and chair of the state transportation committee, alongside this author.

The primary task of the study, referred to as Phase One, was to generate three concept plans for how the corridor might better satisfy the community’s vision for the street, while still preserving its transportation role. In order to do this, the Study Team aimed to accomplish a lot on a limited budget. These goals included bringing voices into the discussion that had typically been excluded from the planning process which produced the 2006 Traffic Plan, building public understanding of transportation planning issues, and deepening the community’s thinking about what the roadway could be. The City hired a consultant team lead by Lucy Gibson of Smart Mobility, a small transportation planning firm that was leading the way on concepts like roundabouts and road diets. Mitchel Rasor provided urban design expertise. The public advisory committee, emphasizing community engagement, held over 25 meetings with local stakeholders, which included workshops where members of the public could engage in hands-on planning activities and provide feedback on committee work.

Rethinking the Roadway and Traffic Planning Concepts

Following the failure of the 2006 Traffic Plan, there was a growing understanding of the troubled history of Franklin Street. Portland’s Historic Preservation officer, Scott Hanson, assembled a slide show describing the architectural and cultural history of Franklin Street prior to the destruction wrought by urban renewal. Tom Bell, a veteran reporter with the Portland Press Herald, wrote a series of in-depth articles about the study process and the history of the road. There was a buzz about the city, a sense that Portland was ready to do something big, something that reflected the aspirations of the city.

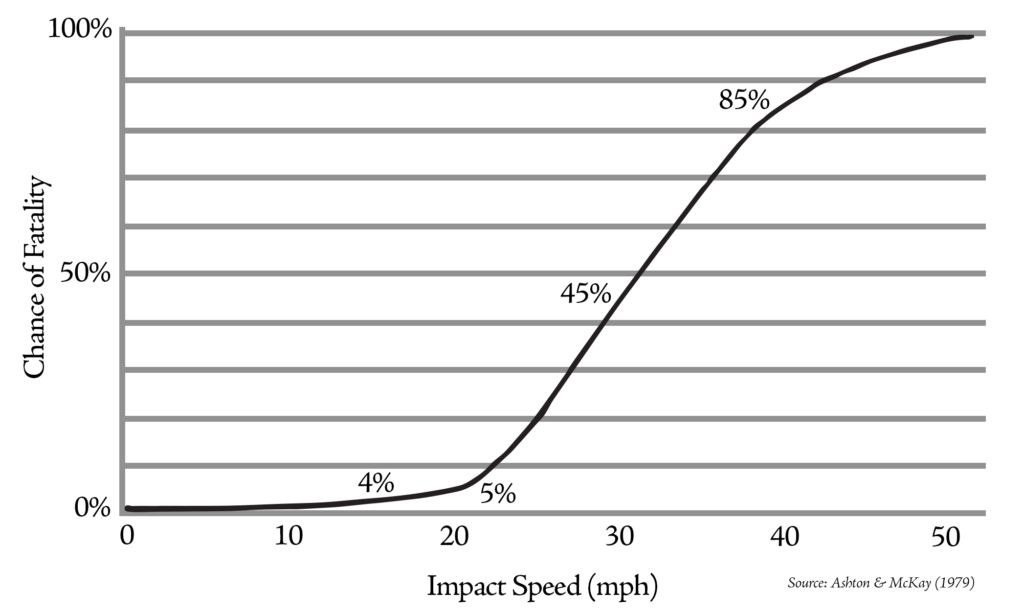

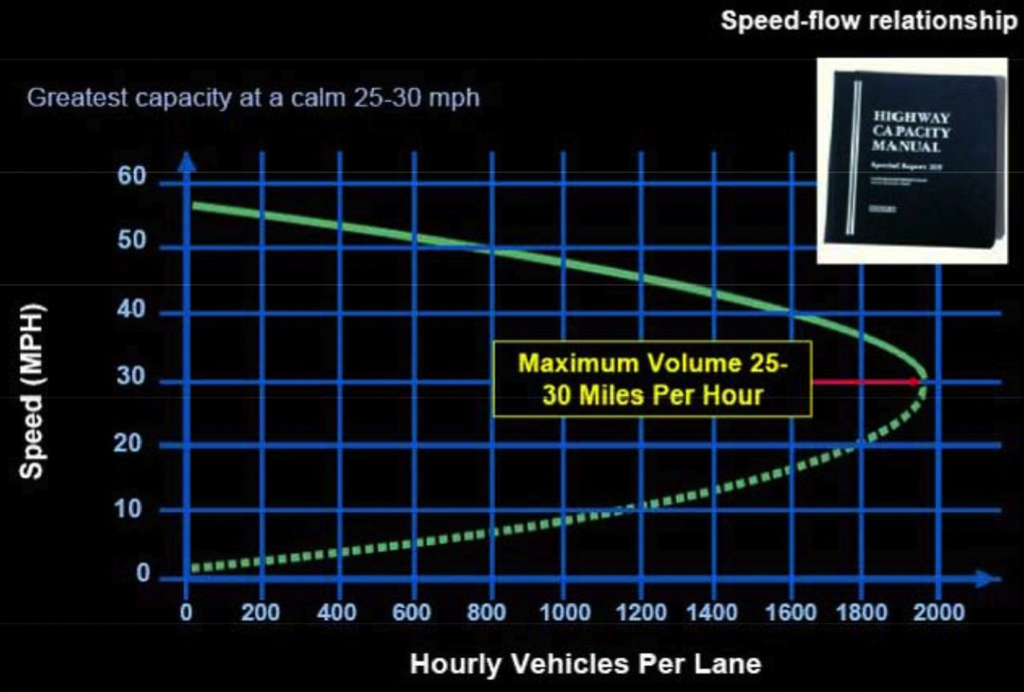

The golden rule of consulting is that if what you’re doing isn’t working, do something else. If an innovative planning process was to avoid the same mistakes, it had to apply the data using a different lens. For example, mobility and safety are supposedly two pillars of transportation planning, but for decades these pillars had been supporting the construction of roads that were less and less safe. The Transportation Research Council’s Highway Capacity Manual, considered the ‘bible’ of roadway design, provides detailed information on optimal travel speeds in relation to roadway capacity, as well as to injuries and fatalities.

Viewed independently, these charts provide some reservations about fast roads. However, when viewed side by side, they send a clear message that urban traffic should move at no more than 25-30 miles per hour. At these speeds, cars can more safely travel close together, maximizing the capacity of the roadway, while significant injuries and fatalities are dramatically reduced in collisions. Another case is found in the use of future traffic projections, which seem to always predict increased traffic, even when historic traffic counts for Franklin Street showed virtually no change in traffic volumes over a 30-year period.

Decreasing traffic volume through the corridor was another important data point that needed to be revisited. At the time of the study, approximately 28,000 cars used Franklin Street at Marginal Way on a daily basis. However, this decreases by a third by the time you reach Cumberland Avenue, and another third beyond Congress Street. Franklin Street sees only about 5,000 cars at Commercial Street. This revealed how overbuilt the lower half of Franklin Street is; there is simply no need for four lanes of traffic south of Congress Street. There are better uses of this prime real estate anyhow, among them more adequately connecting the Old Port to India Street and the Eastern Waterfront.

Phase One: Design Concepts Generated by the Public

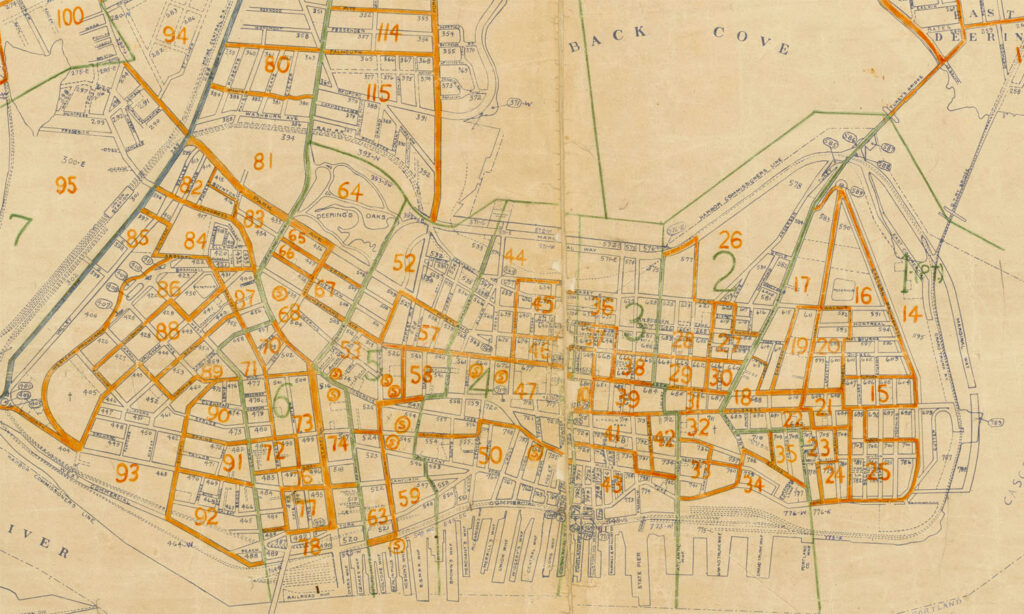

The PAC’s focus on public engagement and community education culminated in a public design charrette at Ocean Gateway in the spring of 2009. Over 100 people attended, not counting the advisory committee and another score of city staff and volunteers with expertise in graphic design and group facilitation. Following a brief presentation of background information about Franklin Street and urban planning concepts, participants got down to work in small groups. Over a dozen teams created visual representations of their shared vision for the corridor. They moved the road, reconnected cross streets, placed crosswalks, sidewalks, and bike paths, designed buildings, and created parks and public spaces.

Three basic designs concepts emerged from the 2009 design charrette: the urban parkway, the urban boulevard, and the urban street. The “urban parkway” pushed the travel lanes to one side and created a linear park running from Back Cove to the Waterfront. This tree lined space provided generous biking and walking paths. The “urban boulevard” provided travel lanes in the center of the corridor for through traffic, and separated side streets running parallel for local access. These were separated by tree lined medians and gardens. The “urban street” pushed the travel lanes together and shifted the road to one side or the other of the corridor, creating developable land parcels adjacent to existing lots and development. In each of these concepts, buildings came up to the right-of-way, fronting the street, with sidewalks and bicycle facilities. There was also a strong desire to reconnect the cross streets like Lancaster, Oxford, Federal, and Newbury Streets. Many groups showed land being restored to historic Lincoln Park, which lost one-third of its acreage to urban renewal. Some groups even experimented with roundabouts at key intersections.

Phase Two: The Stakes Get Higher

The ideas generated in Phase One of the study were generally considered a success. Each concept was considered potentially viable, and the community was highly engaged in the redesign process. Based on the report of the Phase One work, “Reclaiming Franklin Street,” the City of Portland and PACTS agreed to fund a feasibility study of the three design concepts. This funding was later increased with funds that had been set aside for redesign work of the Marginal Way and Fox-Somerset Streets intersections, which is a priority for MaineDOT. This Phase Two of the study was intended to arrive at a final recommended design plan that would be supported by a basic level of design engineering analysis. The gravity of this work brought more stipulations and a greater level of involvement from MaineDOT, which had expressed concerns about the three design concepts. Before Phase Two began, the City of Portland signed an agreement with MaineDOT that the roadway’s Level of Service (LOS) must be maintained in any new design, and there was also growing concern about traffic backing up onto Interstate 295 at the off-ramps of Exit 7.

Level of Service (LOS) was going to be a tricky issue. LOS is a standard metric used for the evaluation of the effectiveness of an arterial corridor. The grading system rates street intersections from A (highest) to F (lowest). Factors include travel speed and time, volume of traffic, and delay. The letter rating obviously corresponds with our educational grading system: A is great, F is failure. To oversimplify just a bit, fast streets get As and slow streets get Fs, and C streets could probably be doing “better.” The metric encourages the design of fast streets – streets which move a lot of cars – even if these are not safe streets. LOS might be an appropriate metric for a highway or limited access road, as the urban renewal-era Franklin Street Arterial had been conceived, but it is not appropriate for city streets.

City streets are characterized by diversity, presenting a wide range of transportation options: walking, biking, wheelchairs, skateboards, etc. in addition to automobiles. To achieve Level of Service “A,” cars are not going to stop at many red lights or wait for old ladies to cross the street. City streets cannot function at LOS A; well-functioning city streets typically function somewhere between Level B and D. It should be noted that the current arterial design of Franklin St. functions at level C or lower at its most critical intersections. The street’s design allows cars to race down to the Marginal Way intersection by Exit 7 where, at peak hour, they must wait multiple traffic light cycles before they can be absorbed into the flow of highway traffic. Faster travel speeds and fewer intersections along most of the street’s length reduce travel times by only seconds. The Exit 7 ramps are the real bottlenecks, and a wider roadway just provides more space for cars to wait at red lights.

In 2011 the City hired a consultant team, led by IBI of Boston and including local transportation engineering firm Gorrill-Palmer, which had worked on the 2006 Peninsula Traffic Study and was well-known for more suburban projects. The public advisory committee (PAC) was contemporaneously expanded to include a wider representation of stakeholders, including more off-peninsula voices. The public process was also now managed by Morris Communications, a member of the consultant team, instead of by the committee co-chairs and the Study Team, as had been the case in Phase One.

Despite the influx of industry professionals, much of the effort was still run with an emphasis on community consensus and transparency. Information was shared with the PAC and members of the public, online resources were maintained and used to collect public input, and the community sustained a high level of engagement in many of the issues related to Franklin Street. The consultant team presented a thorough analysis of the three concepts from Phase One, considering a wide range of metrics, including not only traffic, but development opportunities, creation of public parks and spaces, and impacts on the environment and climate.

Challenging Outdated Transportation Assumptions

In an attempt to address the issue of Level of Service, the Study Team and PAC explored the concept of a multi-modal level-of-service (MMLOS), which would not only consider how people in cars moved in the corridor, but also people walking, biking, and taking transit. Since the current Franklin Street design scored poorly in these categories, it provided an opportunity for gains in transit, biking, and walking to offset any decreases in auto-centric LOS. This tool was adopted into the planning process, but the transportation analysis still focused largely on vehicular traffic.

Portland’s Bayside Trail had been completed in 2010. The trail crossing at Franklin Street was a concern for trail advocates, and many were able to visualize a safe at-grade crossing for the trail. Throughout the Franklin Street planning processes, the guiding vision statements guiding this work clearly called out the primacy of at-grade crossings along the corridor, but yet some people were unable to visualize anything other than a pedestrian bridge over Franklin Street.

The Trust for Public Land, which was helping to fund the Bayside Trail, was strongly advocating for a pedestrian bridge, and had prepared a presentation highlighting some of the world’s most spectacular pedestrian bridges to drum up support. In reality, there was no budget for such world class bridges, and a Franklin Street bridge would have been a quarter-mile-long concrete ramp topped with chain-link fencing as a “safety” feature. Opponents of the pedestrian bridge recognized that the raised crossing would strengthen the message that the street is not a space for pedestrians, do nothing to improve the street, and provide a quick “out” for those who could not see the value in a vibrant urban street: “We gave you this million-dollar pedestrian bridge and you still want us to redesign the street for pedestrians, and bikes, and housing?”

Traffic projections have long been the bugbear of transportation planning. Most of the data analysis underlying traffic projections takes place in the “black box” of traffic engineering. The public and policy makers rarely see what goes into the box or what happens in the box, managed by a relatively small group of specialists. As a result, it is very challenging for laymen to think critically about the process and the conclusions. In recent years we’ve made great strides in considering the biases and unexamined assumptions which underlie “neutral expertise” across many contexts. Yet, this is still not the case for transportation planning. Traffic projections almost always show increased traffic, and the response is to build more roads and wider roads. T4America has does some valuable work educating the public about what goes on in that “black box”. It’s less scientific than you may think.

The Franklin Street Phase 2 Final Report included little information about traffic projection, other than numbers for estimated peak-hour volumes in the target year of 2035. Naturally, these predicted more traffic in the future, even though Franklin Street traffic volumes had been fairly consistent for over 30 years. The Phase Two report does, however, reference a traffic report document that had not been shared with the public. The Franklin Reclamation Authority recently obtained a copy of this and will review it to better understand the assumptions and input underpinning the projected increase in traffic. Everyone who cares about streets, traffic, the built environment, public expenditures, public health, and the climate should care about traffic forecasting, and have the necessary knowledge to think critically about it. These forecasts have transformed the landscape and quality of life around the world.

Political Challenges

Political challenges also arose during the Franklin Street planning process. Paul LePage was elected governor of Maine in 2010. He quickly moved to abolish the state planning office and cancelled nearly all state funded planning efforts. This included Franklin Street in April 2011, in part because MaineDOT was rethinking their commitment to the redesign process. With the assistance of State Senate President Justin Alfond, the Study Team and PAC leadership were able to gain an audience with newly appointed MaineDOT commissioner, David Bernhardt, to convey the goals of the project and how important it was to the Portland community. Contrary to a common perception of the LePage administration, it was a reasonable discussion, and it ended with the commissioner ultimately agreeing to let the Franklin Street study proceed.

The Plan

Finding Agreement on Design Features

In many regards, the study was moving ahead successfully, and soon a concrete – if still skeletal – Master Plan had taken shape. The analysis of the three concept plans resulted in the PAC and Study Team selecting a version of the Urban Street concept. The travel lanes were to be pushed together, freeing up public land on one side of the road (or the other) for development and other public amenities. The road alignment was shifted so that this land would abut as much under-utilized public land as possible, land owned by the Portland Housing Authority (PHA), the city, and the county. PHA’s campus improvement plan for the Kennedy Park campus is based, in part, on utilizing reclaimed land on the east side of Franklin Street. The chosen alignment also attempted to honor what little remained of Franklin’s existing street wall found in buildings like the Archdiocese Parish Hall.

Removing the wide median between the travel lanes together also resolved the issues of cars trying to turn left at Cumberland and Congress Streets. These are currently dangerous intersections where left-hand turning traffic easily backs into the Franklin Street travel lanes. With the addition of left-hand turning lanes, these intersections would function like typical city intersections. Shifting the travel lanes to the east at Congress Street also allows for the restoration of land to Lincoln Park, which lost one-third of its acreage to urban renewal.

Restoring the Traditional Street Grid

The PAC membership had a strong interest in restoring as much of the traditional street grid as possible. A robust street grid can help to sort local traffic from through-traffic, maintain slower travel speeds, and provide more frequent crossings for pedestrians and cyclists. It is, simply, an important part of a walkable city. The current design of Franklin Street forces all users onto Franklin, regardless of their destination, and offers few places for people to walk or bike across. The reconnection of the cross streets, like Federal and Oxford Streets, allows local traffic to more easily cross Franklin Street without having to go up or down Franklin Street first. This frees up Franklin’s capacity to better serve commuter traffic, and improves the flow to Interstate 295.

But MaineDOT was reluctant to endorse connections of the four historic cross streets. The final design only calls for a full reconnection of Federal Street, which became an important connection in the traffic modeling performed by Gorrill-Palmer. Historically, Oxford Street served as a vital east-west corridor and provided trolley service, bringing workers from the west, along Park Avenue and Portland Street, to Washington Avenue. The Master Plan design does include right turns in and out of both sides of Franklin Street at Oxford Street, with an agreement that MaineDOT would consider a full reconnection as traffic data was collected with renewed activity at these intersections.

The Oxford Street crossing would include a signalized crossing for people walking and biking. It should be noted that the restoration of Oxford Street is the one part of the approved plan that impacts private property. The City ceded ownership of a short strip of the street to the west of Franklin Street, now owned by the Noyes family and used as an entrance to their storage and moving company. The community garden and orchard may also be encroaching on the Oxford Street right-of-way on the east side of the street.

Right hand turns in and out are also included on the west side at Lancaster and the east side of Newbury, but MaineDOT would not support full reconnections or crossings at these locations. This became a point of dissent with some members of the PAC.

Most of Franklin Street’s traffic has peeled off by the time it reaches Congress Street. This allows the street to be significantly narrowed to the south, accommodating the restoration of land to Lincoln Park and the narrowing of the roadway. At Middle and Fore Streets the four-lane design currently functions as a two-lane road anytime a car is attempting to make a left-hand turn. The final design acknowledges this by providing a dedicated left-hand turn lane and a single through lane each way. A roundabout is placed at the Commercial Street intersection to integrate pedestrian activity with the slow movement of traffic.

Reclaiming Underutilized Land

The promises of the Franklin Street Master Plan lie not only in the re-orientation towards multi-modal needs, but also in the freeing up acres of under-utilized land for housing and economic development. It has tremendous place-making potential. Unfortunately, the Master Plan does not fully explore these opportunities. Funded largely by federal highway monies, the study could not veer too far from the transportation context. This is a shortcoming of drawing from specific funding pots as well as the removal of land-use context from transportation planning. We plan roads first, and then decide how the land will accommodate all the cars, instead of planning the development we want and then planning how people will arrive at (or live in) the development.

The Master Plan has only a superficial analysis of how to best use the land reclaimed in the redesign, and how the size and alignment of the road impacts this. Greater consideration of these factors, as well how new development might interact with existing buildings and adjacent lots, is needed. New federal programs like the Reconnecting Communities grants, implemented by the Biden Administration, aim to better integrate land use and transportation planning. Franklin Street would be a strong candidate for such funding programs.

Interstate 295, Exit 7, and Franklin Street

At the other end of the corridor, the Marginal Way and Fox/Somerset Street intersections presented greater design challenges. About 28,000 vehicles travel through these intersections on a daily basis. This number has been fairly consistent for over 30 years. Traffic does back up onto I-295 at the northbound exit ramp during morning peak hours, and along Franklin going northbound at peak afternoon hours. However, this is as more a function of the highway and the exit ramps than it is of Franklin Street. Only so many cars can pass through the on- and off-ramps in a given amount of time, far fewer than can arrive by Franklin. Cars back up, waiting to pass through the bottleneck of the exit and on ramps.

The 2006 Peninsula Traffic Plan called for more lanes, basically just to hold cars while they waited for traffic lights to change. You could get more cars to the intersection, but you couldn’t get them onto the highway much quicker. The problem here is not Franklin Street, but I-295 and Exit 7. During Phase One of the study, Federal Highway Administration official, Gerald Varney, admitted that Exit 7 at Franklin Street should have never been built – its proximity to the Forest Ave and Washington Avenue exits make it unsafe. Yet traditional traffic planning has continued to double down on making Franklin Street into the solution for this problem, even if it means adding lanes to serve as functional parking lots.

During Phase Two of the study, a line was essentially drawn at Fox and Somerset Streets, and MaineDOT and Gorril-Palmer used old-school strategies to try to “keep the cars moving” through these intersections. The public process took a back seat as traffic planning moved out to Augusta and onto computers, using sophisticated traffic modeling tools. A lot of time and money was spent with little involvement from the PAC or the public. The result is more lanes, larger intersections, turning restrictions, incomplete infrastructure for people walking and biking, and a design that is more representative of I-95’s Exit 48 or the Maine Mall (in the spirit of Victor Gruen) than Portland. In essence, it extends the off and on ramps up a whole city block to the Fox and Somerset intersection with Franklin Street. Due to the number of lanes and the minimal median at this block, there is no significant land reclaimed. The Master Plan does not transform this intersection. Since the plan’s adoption in 2015, Portland completed its new comprehensive plan, which includes a future transportation strategy – one in which highway infrastructure shall not impact city streets.

The intersection design falls short of offering a “gateway experience,” but does offer some improvements to the status quo. The crosswalk at Marginal Way will be shortened so that people can cross in one traffic light cycle, instead of having to wait mid-crossing on the narrow concrete island. The crosswalk will also be much wider, with an improved alignment along the Bayside Trail. The Bayside Transportation Master Plan includes an alternative design for the Franklin Street/Marginal Way intersection, which could be revisited.

The Devil’s in the Details

The Franklin Street Master Plan also calls for generous sidewalks on both sides of the street, running the entire length of the corridor, as well as bike lanes. More recent discussions have considered a raised, separated cycle track instead of bike lanes, but no information about this has officially been shared with the public. Intersection design is a shortcoming of the Master Plan. Most of the intersections are currently designed with very wide turning radii to accommodate tractor-trailers; this results in longer pedestrian crossings or crosswalks that do not line up with sidewalks and pedestrian desire-lines. Some intersections are also excessively wide, allowing for additional traffic lanes.

Reconstruction Costs and Phasing

The price tag for the reconstruction of Franklin Street was approximately $22 million in 2015 dollars, according to the final report. Some critics of the plan have quoted the cost as $40 million, which had been listed in an early draft of the study report. This higher cost included the cost of Portland’s sewer separation project along the corridor, as it made sense to complete the two projects at the same time. The costliest part of the sewer separation was at Marginal Way, this part of the project was relocated to Back Cove and is now being completed. Preliminary engineering reviews later completed also showed that some of the work could be completed less expensively than originally estimated.

The final study report also breaks the reconstruction into phases, starting at Commercial, where the project is simpler and less traffic would be impacted. The report recommends that the portion of the street from Exit 7 to Oxford Street be completed in the second phase. The final phase would run from Oxford to Middle Streets, connecting the two ends of the street and unlocking the vast majority of the land for re-use and redevelopment. Since the study was funded with federal transportation dollars, there was a shortage of specific land-use recommendations, with only vague considerations offered.

Jon Jennings and the Final Study Report

As the Franklin Street study was winding down in 2015, the Portland City Council hired John Jennings to be the new City Manager. This was around the time that MaineDOT and the traffic engineer team were working on the Marginal way intersections with minimal citizen involvement. Jennings was opposed to the traffic planning Portland had been deeply engaged in, like restoring two-way traffic to State and High Streets and the Franklin Street plan. Communication with staff became less frequent, processes became opaque, and eventually most citizen-led task forces were disbanded by the City. An incomplete draft of the Franklin Street Master Plan was presented to the City Council, and the Franklin Street public advisory committee never received a final copy of the report. Public Works Director, Mike Bobinsky, who was deeply involved in Franklin Street planning for nearly a decade, was fired, other key staff eventually retired or left City Hall. Local members of the consultant team said they were unable to get future work with the City. Some of most supportive city councilors, like Kevin Donoghue (who served as co-chair of the Phase Two study), David Marshall, and John Anton, also chose to leave the Council.

Eventually, the final report was released at a poorly-advertised public meeting. The members of the PAC had not been invited, although some did still attend. The final report included preliminary design review (PDR) work completed to a 20% level. PDR work can include an analysis of environmental, geotechnical, and topographic issues, as well as utilities and existing infrastructure. The original Request for Proposals for the Franklin Street Study called for a much higher level of completion of PDR work, which is required for environmental reviews, but much of this budget was eaten up in the Exit 7 design work – that final part of the study which lacked close citizen involvement.

When the City and Gorrill-Palmer finally presented the final report they also shared a novel Franklin Street design that had never been shared with or discussed by the PAC or the City Council. This alternative design included the enlarged intersections, but left the current street configuration otherwise untouched. It did not realize any of the pedestrian or bicycle gains of the Master Plan, nor did it reclaim land for redevelopment. It was never made clear who asked for this design, but even Chris Branch of Portland Public Works, and the Gorrill-Palmer consultant agreed that it did not align with the stated vision for Franklin Street. It may have been produced at the initiative of City Manager Jennings. In any case, this watered-down alternative was met with uniformly negative responses, and it hasn’t been seen since.

Dormancy and the Future

Missed Opportunities Since 2015

There have been significant changes along parts of Franklin Street since the adoption of the Master Plan in 2015. Some of these presented opportunities to take small steps forward in the redesign. For example, Chip Newell, of NewHeight Group, built two new condo buildings alongside Franklin Street, between Federal and Newbury Streets. The original designs had the buildings backing up to the street, with no entrance onto Franklin Street, just like the last 50 years of development in the corridor. Community members encouraged Newell to have the buildings face Franklin Street, and while Newell showed an initial interest, he said he would need the partnership of the City to make this happen. Setting the location of the curb, along with the creation of a more inviting pedestrian realm, could have enticed the developer to embrace Franklin Street as a primary entrance.

These projects also presented an opportunity to establish reconnections of Newbury and Federal Streets on the east side of Franklin Street, as called for in the Master Plan. The grade changes here are minimal and this could have been a low-cost effort to restore lost connectivity. Councilors Ray and Ali both met with members of the PAC about these issues and agreed to discuss them with City Manager Jennings, but nothing ever came of these efforts. Newell did agree to place a door on the Franklin side of their buildings in case changes were eventually made to the street.

Similarly, there have been several projects along the street that presented opportunities to run trials of some of the design recommendations, and to collect data on their effectiveness before construction. In some cases, travel lanes have been closed for construction on adjacent lots, in effect modeling in real time the effects of a narrower street. These were clear opportunities to collect data on how fewer lanes would actually affect the flow of traffic, instead of just relying on computer modeling. There were some efforts to do this by Portland’s traffic engineer Jeremiah Bartlett and Traffic Planner Bruce Hyman, but these efforts did not advance in the Jennings administration.

Likewise, many of the design recommendations south of Congress Street could easily be implemented on a temporary basis at a very low cost using tactical urbanism techniques. Tactical urbanism seeks to make small incremental changes with simple design interventions on the built environment using low cost, temporary materials. For example, painting temporary crosswalks at intersections which currently don’t have any. Data can be collected, designs can be improved, and the final design is made more effective thereby. The travel lanes and intersections at Middle and Fore Streets could easily be modified with the addition of temporary bike lanes, food truck courts, and public spaces, all short-term measures which could bring more activities and transportation options to a relatively vacant part of town. There has been little leadership on these issues at City Hall.

Looking Ahead

There have been several funding opportunities to implement the Franklin Street Master Plan since 2015. The Obama and Trump Administrations had major infrastructure programs, like BUILD and RAISE respectively, which were well-suited for the Franklin Street project. The regional transportation planning organization PACTS has repeatedly placed Franklin Street on its priority list, a necessary step for federal funding, and our local congressional delegation has demonstrated interest (and has adequate clout) to secure funding. However, the City of Portland has been reluctant to step up as the key partner needed to move forward.

Now that Portland has moved beyond the Jennings Administration, the Charter Commission, and the hiring of Danielle West as the permanent City Manager, there are signs that the City is ready to take the next steps on Franklin Street. City Councilor Andrew Zarro, who chairs Portland’s Sustainability and Transportation Committee and is currently running for Mayor, has worked with other councilors and staff to advance Franklin Street. There are signs that the few remaining staff members who were involved in the planning process care about this effort, and have continued to work on it over the years.

There are also signs of gradual change at MaineDOT. As the Phase Two study was winding down, MaineDOT’s chief engineer, Kenneth Sweeney, was retiring. He had served for 50 years, and had instilled an old-school, auto-centric approach to transportation planning within the department. His successor, Joyce Taylor, is the first woman to ever hold this position, and comes from a younger generation. At the 2022 Build Maine conference in Skowhegan, Taylor told this author she was open to moving forward on Franklin. Institutions like MaineDOT change slowly, but the last 8 years have shown signs that MaineDOT is thinking more creatively about transportation and its impact on communities.

In 2022 the Biden Administration signed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act into law. This included a number of funding sources that are opportune for Franklin Street, most notably the Reconnecting Communities grant, which aims to repair some of the damage caused by the urban renewal projects by creating safer streets and stitching neighborhoods back together. It is an important step in linking transportation and land use planning. The City of Portland must be the principal applicant for these funding grants, and MaineDOT probably needs to play a supporting role.

The Franklin Street plan could also be funded locally. Reclaimed land could be sold, with these profits going towards paying off the reconstruction costs. Future tax revenue from redeveloped parcels could also be used to offset costs and provide additional revenue for the City. The reclaimed land could also be designated for affordable and workforce housing while still generating future tax revenue. These issues of financing and re-use need to be further explored and discussed in a transparent manner.

Portland’s City Council has planned a workshop on Franklin Street for September 11, 2023. This follows up on brief committee presentations earlier in the year. Councilor Pious Ali is the only current councilor that was serving when the Master Plan was approved in 2015; in other words, there is a lot to catch up on. The City is also preparing an RFP for follow-up work on the Franklin Street plan. Details haven’t been released yet, but one hopes that the goal is to improve upon the plan and develop it such that it would be eligible for the federal funding programs now available. These funds are limited and will not be available forever, Portland will need to act.

In the third and final part of this series on Franklin Street, I will discuss key issues the next phase should address in order to maximize the benefits of the roadway redesign and contribute to a more sustainable city.

Markos Miller – Markos is a founding member of the Franklin Reclamation Authority and served as the co-chair of both phases of the City’s Franklin Street Redesign Committee from 2008-2015. He is an educator, community organizer, and resident of Munjoy Hill.

I have a couple of thoughts regarding driving in Portland. I live on Peaks Island and use Franklin Arterial often. The traffic light at Commercial and Franklin is VERY short, and MANY times pedestrians walk, even though their walking light tells them Not to walk, and I am forced to wait and miss the green light. If there was a “round about” I think even more pedestrians would think they had the right to walk in front of traffic. Traffic going along Commerical Street often does not stop soon enough and blocks the intersection so I can’t use Franklin then as well. I love the idea of a walking city, and that’s what the side streets should be. Franklin should be a quick way to enter or exit the city. Many streets have been changed to one, or two lanes and impede traffic flow. I think not All streets should be pedestrian walkways, 295 isn’t. I thought changing the parking on Commercial St. to allow for bigger sidewalks was okay and then the restaurants were allowed to use that space for outside dining. So, parking spaces were lost, and, we still didn’t have an adequate sidewalk. What’s to prevent that from happening again? I am very interested in how Franklin changes, I hope for good changes that make me want to keep living here. Not just changes for the tourists and what they might like.

Imagine the following scenario. A group of concerned citizens become fed up with the crowds and lines on the Casco Baylines Ferries and ask their representatives to “do something.” Federal funding gets secured and Franklin Street gets extended to the Maine State Pier and then a Bridge leading to Welch Street on Peaks Island. The intersection of Welch and Island Avenue is reengineered to accommodate interchanges for the new 65mph grade A LOS Peaks Island ring road (Renamed the Casco Bay Parkway). 68 homes and businesses are demolished to achieve the necessary road improvement and another 153 homes are likewise demolished to build four interchanges at key points around the island. Naturally pedestrians, cyclists, and golf carts are restricted on the the new parkway but they may still uses the interior side streets all of which has been converted to metered parking. In phase two a spur is added at Central Avenue leading to a 5-story garage at the site of the current ball field. Having solved the problem of the crowded ferries government officials, consultants, and contractors move on to the next project leaving the original group of concerned citizens wondering if they are really better off.

Zack, be sure the WB67 semi-trucks than make all those turns as they drive around the island!

The Master Plan maintains Franklin’s role in getting people into tan out of the city. It even makes it do this better, improving 21 of the 22 points where MaineDOT collects data. Island residents and representatives were largely in favor of the roundabout option- the current crossing is so wide that pedestrians feel they must make risky movements to get across. A roundabout narrows the distance to walk across, resulting in more pedestrians pausing for traffic before crossing.

I think your point about who we are improving the city for is valid. We should be perusing opportunities to make our city better- but for residents and the people we need to have functioning city- a diverse and talented work force. But a heavy focus in tourism turns us into a facade of a city, one that does not meet the needs of the people that made it what it is.

To elaborate on the point of I-295 and Franklin St. backups “…this is as more a function of the highway and the exit ramps than it is of Franklin Street”: we were told by several members of the public that they avoid using the Forest Avenue (Exit 6) interchange because of its poor design leading to unsafe conditions – perceived and actual. This is self-evident.

As a member of the PACs and of Franklin Reclamation Authority, though we were limited in the scope of what we could study in all phases of study, this overuse of Franklin St (Exit 7) directs the true problem back to I-295, and a need to look at the entirety of it on the Portland peninsula.