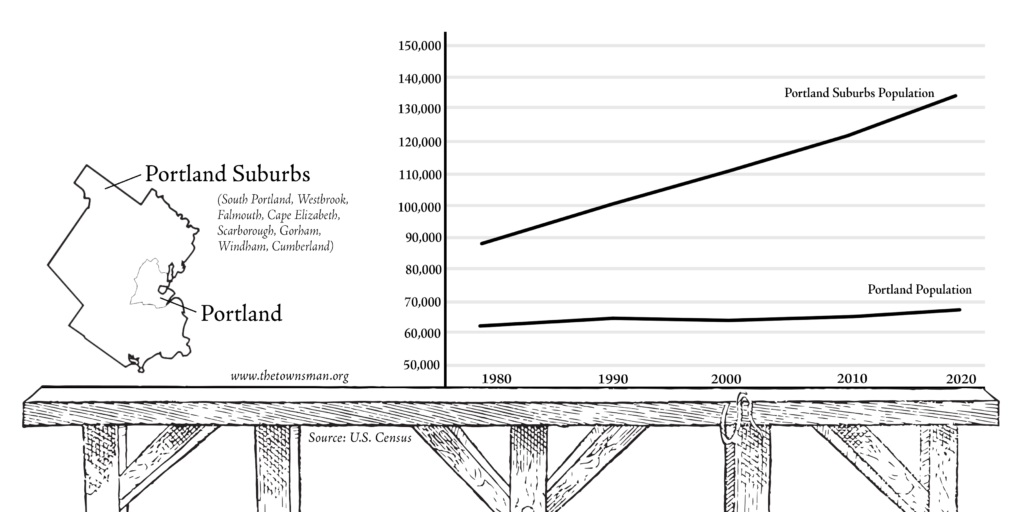

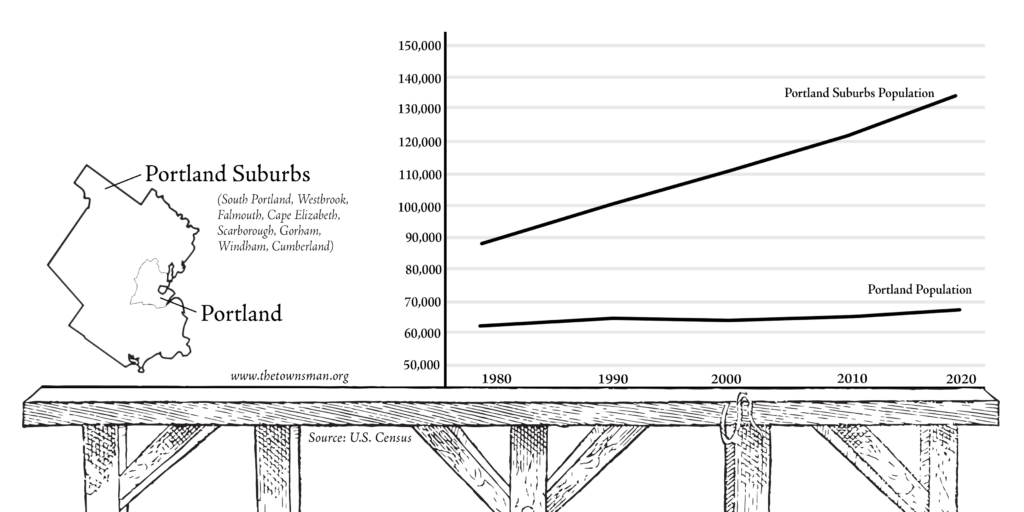

Contemplating this chart, what can one conclude about Portland and its suburbs? The fact that population continues to rise rapidly in the Greater Portland area, while staying flat within the city limits, (and also staying relatively flat statewide,) is clear proof that there is a high demand to live in or near Portland, but that actually living inside of Portland is out of reach for many. Why is this? The failure of city policymakers over decades to allow adequate housing construction is undoubtedly a key factor, (one that hasn’t gone unexamined here at the Townsman,) but let’s suppose that there is more to the story.

All cities, as geographic areas, have limits to how many people will live there. These limits can be increased with infrastructure, technology, and economic incentive, but eventually all cities will start to “overflow” into the surrounding region. This isn’t a bad thing, it’s the fundamental assumption of suburban living. Every person has their own priorities, and some will be willing to trade a longer commute and fewer amenities for greater privacy and lesser density. Such people will be drawn to satellite communities, while others who favor the benefits of city life will be drawn to the urban core. Neither is wrong – but as a city, state, and nation, we make democratic decisions on what our infrastructure will encourage and discourage. The story of post-war urban policy in the USA is one of infrastructural preference to the suburb, the automobile, and the single-family home. But that isn’t what I want to delve into here.

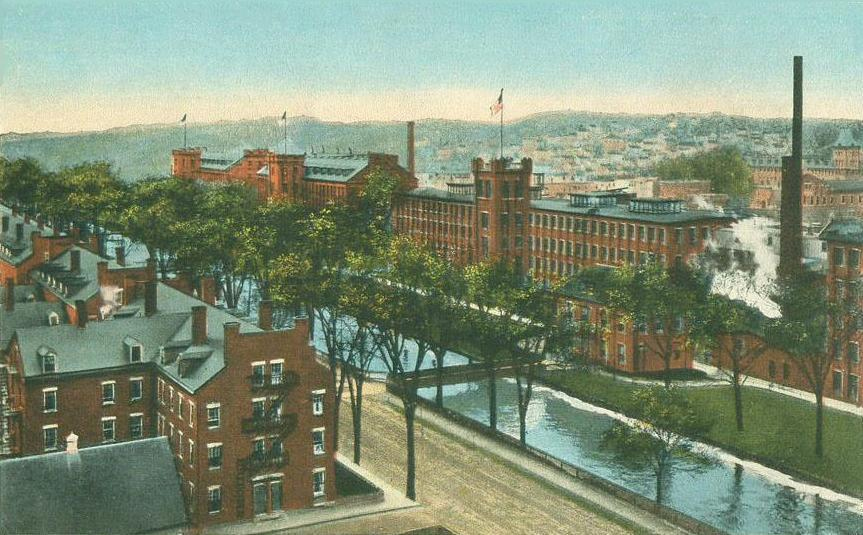

After all, before WWII, this infrastructural preference did not yet exist, and cities were frequently more populous, denser, and supported greater connectivity than they do today. Portland’s population, for example, peaked in the 1950s, and had more citizens in 1920 than it had a century later. Only today is the population beginning to resemble what we had in the 1930s. So, in these prewar cities, where tenement blocks, streetcars, trains, and the pedestrian commute still reigned, did cities still overflow?

Of course they did! Cities would grow, a subset of citizens would seek out more peripheral lifestyles, suburban towns would benefit from the infusion of human capital, the city reaps the rewards of having vibrant suburbs, everyone wins. Right?

Well, there is one key piece of this process that’s missing – urban annexation. As controversial as it is rare in today’s America, this once-commonplace practice used to be as anodyne as paving roads or dredging marshes. The lack of urban annexation in the public sphere has led to many perverse incentives, ones that even well-meaning reformers don’t realize they have fallen prey to.

On the odd occasion, you’ll hear someone say something along the lines of “South Portland, Falmouth, Westbrook, and Cape Elizabeth should be annexed into the City of Portland.” Provocative idea, isn’t it? Even if one is open to outside-the-box ideas for addressing the problems facing Greater Portland, this notion can hit a mental wall. After all, towns can’t do that, just take over other towns? Obviously City Hall isn’t going to send tanks into Falmouth, but municipal annexation is a real process that urban jurisdictions have used to address the very same problems Greater Portland is facing today. Should we consider it now? Economists and political scientists are of mixed opinion, with some championing the benefits to equitable growth, but others decrying the monopoly-like disincentives involved. Residents often feel as though smaller towns offer better representation, but the costs of maintaining so many local governments are a great burden on property taxes. Prior to weighing the merits of the idea, however, let’s ensure we know what we’re talking about.

It’s rare these days, (the last town merger in Maine was in 1922: Dover-Foxcroft,) but annexation has a long pedigree. Residents of the independent city of Brooklyn weren’t too keen on being absorbed into the Gotham Goliath of New York City, (indeed local newspapers of the day called it the “Great Mistake of 1898”) – but today, thinking of the city as meaningfully distinct is something for sentimentalists, not politicians or economists. Queens and Staten Island followed suit. No fewer than twenty-eight (28!) named municipalities were folded into the city of Philadelphia in 1854. Chicago underwent a period of continued annexation, swallowing up suburbs from the mid-19th century into the early 20th. Los Angeles integrated Hollywood in 1910, and several other towns over the next decade. I could go on, almost every major city in America has a record like this.

And of course, Portland itself has profited from this process. Today, Deering is just a collection of neighborhoods, but as long-time residents will romantically tell you, it used to be an independent town. Deering was annexed into the city of Portland in 1899 – despite a vote by its residents opposing the change. And so, the roughly 5,000 residents of Deering became residents of Portland against their will by an act of the Maine State Legislature.

Today, more than a century later, is there a strong separatist mentality among Deeringites? If there is, it hasn’t manifested publicly. Ultimately, the consolidation has been mutually beneficial, and it preceded a period of economic growth and prosperity in the region. Was it a good idea? Even if there are those who think not, it’s hard to imagine anyone getting too up-in-arms about it. Yet after WWII, in line with national trends, Maine hasn’t overseen a single urban annexation.

If patterns had continued as they had been, it would be hard to imagine today that Falmouth, with its seamless connection to Portland, economic dependence, and its small-but-rapidly-growing population, would still be a separate town. Perhaps the same could be said of South Portland or Cape Elizabeth. After all, the 18th century city of Falmouth encompassed modern-day both of those towns as well as Portland, and was only broken up as the technology of the day did not allow for people to conveniently travel between them – but today we certainly can, and we do.

I am not suggesting that all of Greater Portland be consolidated into a single city tomorrow, of course, but it is essential that urban annexation remains on the table as an option, because it is a key tool for preventing policy cannibalism. A prominent judge of the time, Henry Harlan, had this to say in response to the ongoing 1918 annexation of suburbs by Baltimore, Maryland:

“Those who locate near the city limits are bound to know that the time may come when the legislature will extend the limits and take them in. No principle of right or justice or fairness places in their hands the power to stop the progress and development of the city, especially in view of the fact that a large majority of them have located near the city for the purpose of getting the benefit of transacting business or securing employment … in the city.“

The relationship between city and suburb can be a healthy one, however it bears an intrinsic risk of becoming parasitic. Suburbs can profit off of the vitality of cities while giving nothing back. They can see their property values rise from being nearby, without any duty to harmonize housing policies. They can lure business away from the city by offering unsustainable tax or labor policies, ultimately to the detriment of everyone. In southern Maine today, there is a manifold crisis in living standards, and so long as Greater Portland is divided among several municipalities, working at cross-purposes and even racing to the bottom, it may prove difficult to address.

Meanwhile, decisions made in Portland’s city hall will always affect the whole region, but workers, families, and entrepreneurs that live outside of the city limits (increasing numbers of whom were driven out by housing costs) have no say. If a working-class family is forced to move to Gorham to find affordable housing, their votes in Portland have been effectively eliminated. When activists fight for city-level reforms to the minimum wage, businesses can flee across the Casco Bay Bridge to South Portland, or just north along 295 to Falmouth, enriching the suburbs at the expense of the city. Portland can upzone its building codes and draw in development, but unless our suburbs do the same, we’ll still be constrained by artificial restrictions.

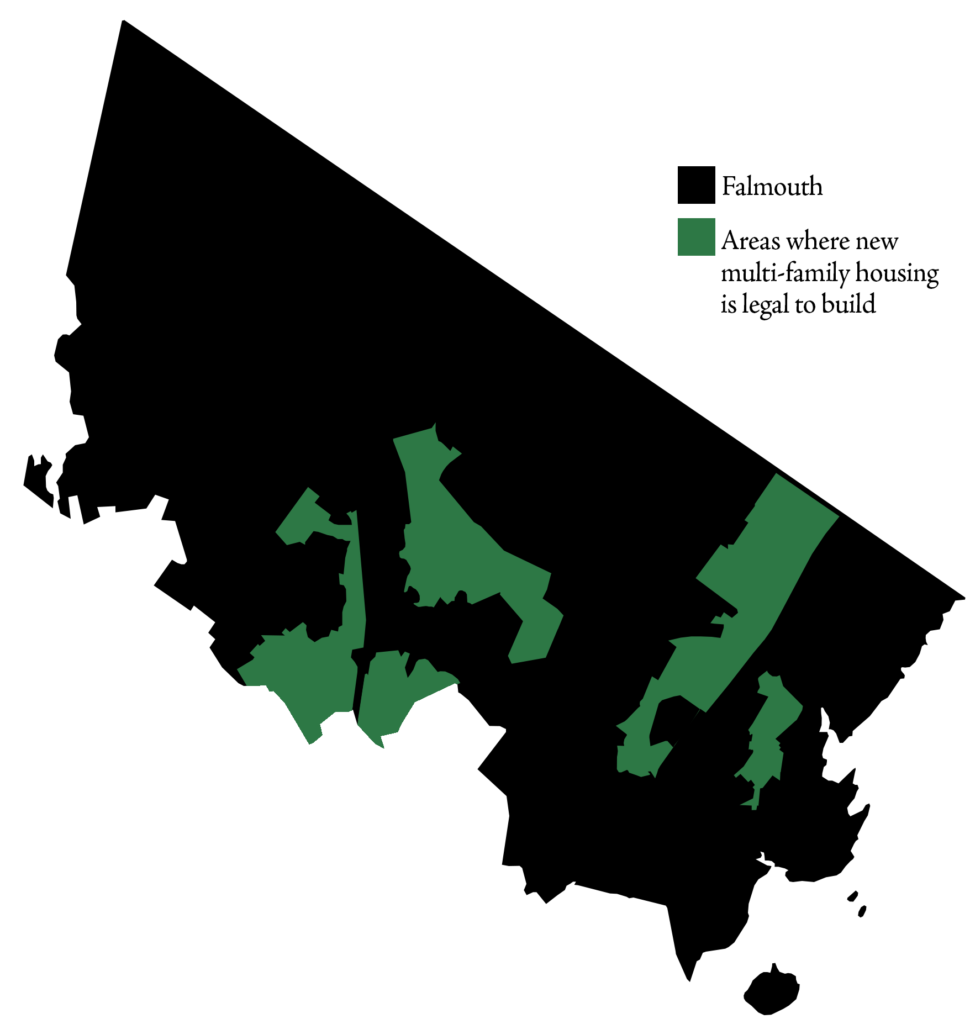

Consider Falmouth, which is so close to Portland’s urban core. This suburb has implemented a very strict limit on development, placing a hard cap on the number of development permits it will grant each year. Only 65 permits for single-family homes, and only 24 permits per year for multi-family homes. It will also grant just 20 permits per year for Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs, also known as ‘Grandparent Housing’) but this may conflict with the recently-passed LD 2003 in Augusta. And even if one does manage to acquire a permit to build, the town’s restrictive zoning plan allows multi-family homes to be built on just a small fraction of its territory. In addition to these formal restrictions, it’s evident that the town government is unfriendly to the idea of significant housing construction. Not all suburbs are this hostile to homes, Westbrook for example is leading the pack, but if we are to address the housing shortage, Falmouth’s intractability will prove a long-term challenge.

Simple finances are a mainstay of pro-merger arguments, having no shortage of redundant administrative functions that could be made much less expensive and more efficient by consolidation. This would, however, almost certainly involve a reduction in municipal employees, striking fear in the hearts of suburban government workers. Police and other emergency units already work closely together across town lines, yet towns pay for duplicate resources. Questions of help for the needy is another constant concern envenoming relations, as suburbs accuse Portland of unilaterally adopting policies that cost everyone, while Portland accuses the suburbs of not doing their fair share. Cooperation on matters of infrastructure and transit are already facilitated by a supra-municipal body, the GPCOG. Isn’t our increasing reliance on governing bodies larger than our towns proof that some level of consolidation may be necessary?

Of course, there are detriments to annexation as well. Business owners in the suburbs are happy to see the DSA laser-focused on Portland, as opposed to state-level politics, and many would be frightened at the prospect of a union of jurisdictions. Meanwhile the progressive reformers of Portland often fear losing electoral power if the conservative-leaning suburban homeowners can all unite. But these petty political concerns shouldn’t be blown out of proportion – to this day one can detect differences of political inclination between Manhattan and Brooklyn, but this doesn’t mean that the merger hasn’t been, in the long-run, a success.

How It Happens

If, hypothetically, you were to support annexing at least one of Portland’s suburbs to the city proper, (let’s say, for example, the most obvious candidate – Falmouth,) how would it be done?

As you probably know, America is a “federal” government, what this means in concrete terms is that there are multiple layers of government with sovereign powers. In other words, there are things that states have the power to do that the national government has no say in. Many people imagine that this is also, in some sense, the relationship between state and local governments. But this is not at all the case. Town governments are “creatures of the state”, and completely at the mercy of the state government in all things. In America, cities have zero sovereignty. As a result, if towns want to do anything outside of what they’ve been explicitly empowered to do, the state will probably need to get involved.

We can separate the annexation process into two broad kinds – cooperative and non-cooperative. Both require the state government’s involvement.

Cooperative Annexation

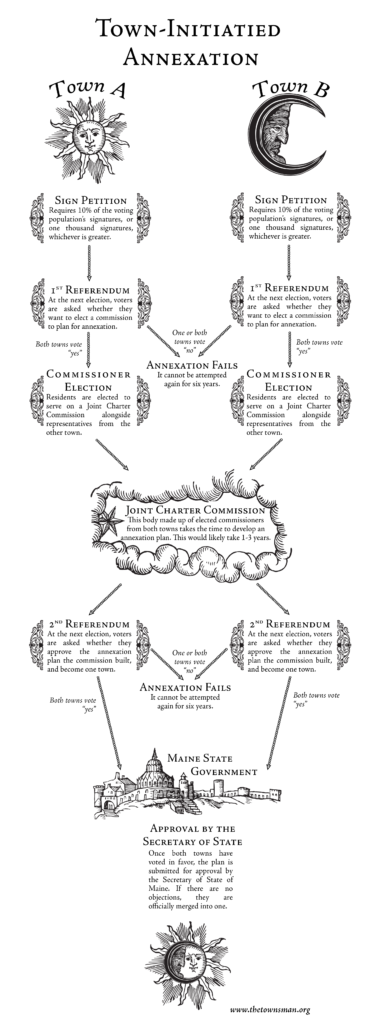

First, let’s assume that we’re dealing with a cooperative annexation, that is, where a majority of the people of Falmouth desire union with Portland, and a majority of Portlanders do as well. This is certainly the most painless method, and boy would we be glad to have you! The process is cumbersome but mostly straightforward, according to Title 30-A, Chapter 113, §2151 of Maine’s statutes. First, voters from each of the municipalities must collect a number of signatures equal to 10% of the votes cast in the previous gubernatorial election, (or 1,000, whichever is greater,) and present this petition to the town officers. If all is in order, at the next election, there will be a referendum question in Falmouth which reads along the lines of: “Do you favor forming a joint charter commission to draft a consolidation agreement for the purpose of consolidating with Portland?” and vice versa in Portland for Falmouth.

Our friends to the north, Lewiston and Auburn, recently made it this far. These twin cities in Androscoggin county, already so intermingled, were asked if they’d like to become a single city. (It almost sounds romantic.) Advocates claimed that the merger would save both cities millions of dollars per year, currently spent on redundant administrative functions, and lead to greater prosperity and equitable growth in both towns. It drew support from across the board, from progressive nonprofits as well as former Governor (and Lewiston native) Paul LePage. But in 2017, this effort went down in flames at the polls, with only about a third of voters in both cities voting in favor. If this wasn’t disheartening enough for supporters, state law bans any attempt to try again for six years. Starting this year, in 2023, advocates will be allowed to go for another bite of the apple.

But if, in our hypothetical scenario, Falmouth and Portland do harmoniously vote to merge, then at the next election after the successful referendum, both towns will elect representatives to a Joint Charter Commission, similar to our recent Charter Commission but for both towns, to begin work on the arduous task of preparing an administrative merger plan. Most towns have further details in their charters regarding this Joint Commission, so the particulars may vary, but the process will likely take more than a year. In the case of Lewiston-Auburn, it was expected to take two. Once this Joint Commission has completed its work, both towns will be asked again, (for those counting, this will be the third election in each town on the subject,) once and for all, if they will accept this arrangement and merge together. If both towns have a majority vote for ‘yes’, then the consolidation agreement will be submitted to the Maine Secretary of State for approval. Unless there are substantial procedural concerns, this step is likely to be a formality, and within months the union will be complete.

So, six elections, 3-5 years, and a strong majority will all be needed, but at the end, Portland and Falmouth will have become one. This is how Dover and Foxcroft, more or less, became one town in 1922, with a new name less beautiful together than either were separately. It, initially, was an unpopular idea, finally pushed over the threshold of majority only by the enfranchisement of women, but today the town is happily unified, celebrating the anniversary of this union each year.

But, what if one of the towns doesn’t have an overwhelming majority in favor? Again, municipalities are creatures of the state, so if the state sees fit to consolidate the two towns anyway, then they have the power to do so. Remember, this is how Deering was annexed into Portland – against the express will of Deering’s residents. This lack of consensus is a very likely scenario for any future merger. A parasitic suburb has every incentive to remain independent, even to the long-term detriment of its own residents and the rest of Maine. Even if a small majority, say 52%, of a town’s voters do support annexation, it would only take one fluke result in the three elections needed to derail the whole process. Realistically, a supermajority is necessary, and a supermajority in anything is hard to come by.

Non-Cooperative Annexation

A non-cooperative annexation, (not to say ‘hostile takeover,’) is entirely plausible. It in fact used to be a completely normal bureaucratic process to do what was best for the prosperity of the state as a whole. How might it be done?

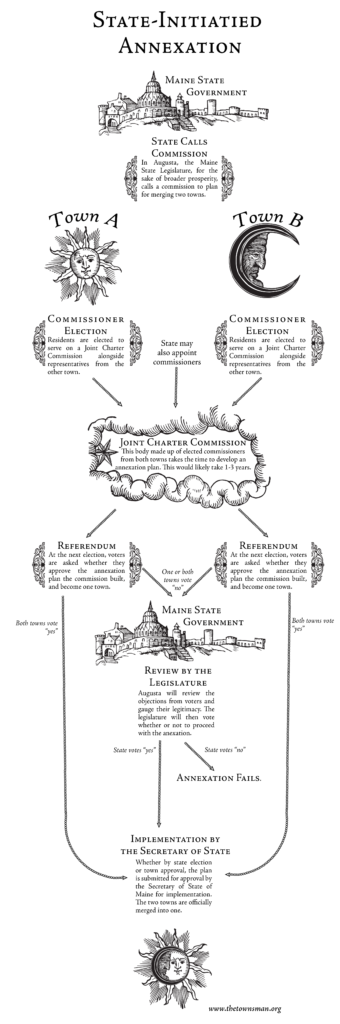

The process for a non-cooperative consolidation is actually more procedurally simple, though it would probably be more politically controversial. As a demonstration, we can look at the process that Portland and Deering went through. In 1898, at the request of representatives from the region, the Maine Legislature voted to call a commission for the preparation of a plan of annexation, merging Deering into Portland. This commission would be made up of neutral non-residents of either town, as well as one representative member of each. After a year of planning, the commission presented its plan to the voters of Portland and Deering and asked them to vote ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to the prospect of annexation. Portland, perhaps unsurprisingly, voted ‘yes.’

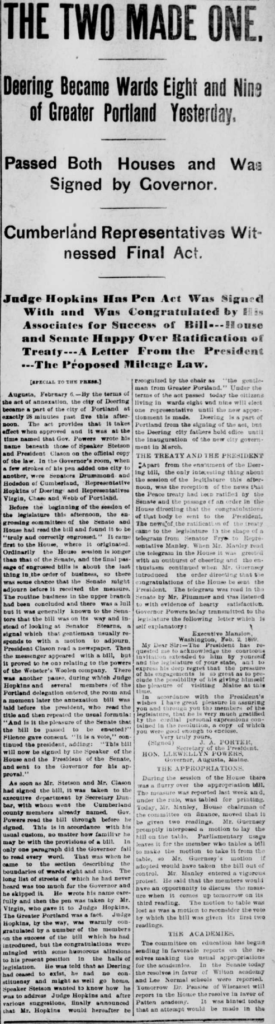

But Deering’s citizens voted ‘no’ in a one-sided referendum. Undeterred, those leaders from both towns who supported the merge appealed to Augusta, citing the importance of the move to regional prosperity. The state legislature agreed with these leaders, and reasoned that the political and economic development of Greater Portland outweighed the objections of Deering’s citizens. Governor Powers, flanked by representatives from southern Maine, signed the bill annexing Deering into Portland on February 6th, 1899.

One of those representatives in the room was Judge Hopkins, who had been elected by the people of Deering. The Portland Daily Press recorded this amusing exchange between Hopkins and the other politicians present –

“The Greater Portland was a fact. Judge Hopkins, by the way, was warmly congratulated by a number of the members on the success of the bill which he had introduced, but the congratulations were mingled with some humorous allusions to his present position in the halls of legislation. He was told that as Deering had ceased to exist, he had no constituency and might as well go home. Speaker Statson wanted to know how he was to address Judge Hopkins and after various suggestions, finally announced that Mr. Hopkins would hereafter be recognized by the chair as ‘the gentleman from Greater Portland.’”

One can almost detect the bittersweet emotions, some sorrow for the ‘loss’ of his hometown, but optimism for the future of his community.

The bill was a remarkably straightforward document, simply and immediately designating the territory formerly known as the town of Deering as wards 8 and 9 of the city of Portland. The lengthiest part of the bill is the intricate division between the two new wards, precisely tracing along the roads and streets a line dividing the former town. Otherwise, the town functions of Deering simply ceased to be operative, and all of their responsibilities transferred to their Portland equivalents. The new wards were asked to hold special elections to vote on their local councilors, but otherwise there was surprisingly little ceremony. As the Daily Press puts it, “By the terms of the act of annexation, the city of Deering became a part of the city of Portland at exactly 28 minutes past five this afternoon.”

In the spirit of our look last time at the “for rent” classified ads from thirty years ago, here’s a quick look at the 1899 equivalent. $15 for a room on Monument Square. About $500 in today’s money. What a deal!So, what can we learn from this 124-year-old annexation? In one sense, very little. We occupy a very different world than our forefathers did, and these politicians – many of whom were Union veterans of the Civil War – didn’t think about local democracy in the way common today. Besides, municipal governments employ far more people today than they did a century ago, so any consolidation is necessarily significantly complicated by a greater administrative burden.

But in another sense, we can at least learn that there’s nothing constitutionally preventing a motivated state government from overseeing such common-sense annexations. This could happen tomorrow, if the votes were there. We can also see an illustration of the often-derided principle of state-level government making decisions for the best interests of the state as a whole – even if it means going against the consensus of a single small town. Regular participation in local politics is typically restricted to a small minority of the motivated, the wealthy, the retired, and the obsessed, excluding the busy workers and families who don’t attend meetings. Some are beginning to question the utility of giving this oddball minority an outsized influence. To apply this same suspicion to state politics, it may be that solving the festering problems in southern Maine will require a steely disregard for the objections of regional minorities.

So, in 2023, a similar process would look more-or-less like this: The state legislatures calls for a joint commission of representatives from Portland and Falmouth to prepare an annexation plan. Once this is prepared, it is presented to the voters of both towns. If both agree, great! But if one town votes against, the state legislature can review the specific objections of the dissenting voters. If these are found to be lacking in substance, then the state can simply override this referendum and pass legislation implementing the plan. All in all, potentially much faster and with fewer headache-inducing and expensive local elections.

~

You may have been reading with horror about this possibility of the state just ignoring the results of local democracy. Isn’t merging together two towns against the democratic opinion of one of them a little tyrannical? You may think so, but consider this: “Democracy” is only a coherent concept when there is consensus about boundaries. Maine voted for President Biden in 2020, but if Cumberland and York counties happened to be part of New Hampshire, then Maine would’ve gone down as a red state. Northern Maine often complains about being unrepresented, overwhelmed by votes from Greater Portland, but why do we ignore them? Why is the border between Maine and the rest of New England where it is? Ultimately, it’s all arbitrary, but the line has to be drawn somewhere. When invoking local autonomy, one can face a sausage-slicing problem, where no matter how local one gets, there’s always going to be a dissenting minority who might try to claim autonomy. In other words – there’s a limit to how useful “democracy” is when talking about local boundaries, because local boundaries define democracy. There will always be some arrangement of borders that leads to one outcome in a vote, and another arrangement of borders that leads to another, so when deciding on what those boundaries are in the first place, one often has to appeal to principles other than simple “democracy” or “autonomy.” I invite you to consider such principles as “justice,” “prosperity,” and “cohesion” in their place.

Certainly, local democracy is an ideal both generally appealing as well as specifically touching to we New Englanders, with our near-ancient traditions of meetinghouse consensus-building. When we were the most literate society on earth in the 17th century, we built our society on the foundation of town autonomy. But modernity has brought with it problems that Puritan ethics can’t always solve.

I call your attention back to this chart, which has been haunting me since I put it together. What I see here can only be described as a massive waste of potential. Greater Portland has everything it needs to care for its long-time citizens, adequately absorb newcomers, and ring in a new era of prosperity for everyone. But we are hamstrung by self-imposed limits, we don’t allow ourselves to react naturally to growth, and we divide up what may organically be a single city into a hodgepodge of local municipalities. Certainly, the existence of the town of Falmouth is not one of the primary causes for the multifaceted crises afflicting us, but consider with care and an open mind how these administrative shackles affect you and your town.

Ashley D. Keenan – Ashley is an editor of The Portland Townsman, writer on urbanism, local small business-owner, and Maine native. Her work primarily covers the national housing crisis, building sustainable and livable cities, responsible market economics, and New England culture and history. She lives in Portland with her fiancé and can be personally reached at ashley@donnellykeenan.com.

Intriguing as always, but wouldn’t this increase the number of nimbys in the city and further burden our city services (like plowing, trash collection, and public transit) that have already been made inefficient by sprawl?

I’m not proposing that urban annexation be considered as a means toward any particular end, in fact I’m not proposing urban annexation at all. In my opinion, Portland doesn’t even have its own house in order, the constraints of the suburbs haven’t really begun to rank highly in terms of obstacles. And besides, the best case scenario would be one in which all the towns engage in healthy growth and mutually-beneficial competition for productivity and efficiency.

However, as the region increases in population, this will become more and more a subject of conversation, and controversy, so my goal here is to illuminate the exact nature and process of urban annexation, and place it in a historical context. This is not a rallying call for consolidation, more just an attempt to elevate the discourse on this subject.